Water Governance from the Perspective of Indigenous Peoples in Papua

Water is the primary basic need for human beings and all living things. It covers approximately 71 percent of the earth’s surface, but only 3.5 percent of this is fresh water, of which 1.7 percent is locked as groundwater and a further 1.7 percent comprises glaciers, ice caps, and vapor in the air as part of the precipitation process. This shows that accessibility to fresh water is limited and that water has become a precious economic resource, especially in light of increasing water pollution and population size.

Water governance should be applied in sustainable ways to protect the availability of water resources, and the knowledge and practices of Indigenous Peoples are there to learn from in this regard. Indigenous Peoples are inseparable from their ecosystems, including water, land, forests, animals, plants, landscapes, and wetlands. They have their own ways of using, planning, maintaining, and respecting nature to support their daily lives. It has been proven that Indigenous people have survived and thrived for thousands of years with their own traditional systems. For Indigenous Peoples, water is not only an economic resource or an environmental service, but has value by itself, in a spiritual way. They consider water and water bodies such as rivers and swamps as having their own spiritual dimensions. 1

Like other Indigenous Peoples around the world, Papuan people have their own ways to value, utilise, and maintain water. Papua has over 269 ethnic groups, 269 living local languages, and 1,068 clans spread across the seven customary zones of the entire Land of Papua (Tanah Papua). These zones are Bomberai, Domberai, Saireri, Mamta, Mee Pago, La Pago, and Ha Anim. This article discusses the Malind Anim people in Ha Anim, the Enggros people in Mamta, and the Sambom people in La Pago.

Despite several of these cultures and local languages having nearly disappeared, many of them still maintain their traditional wisdom, values, and philosophies on how humans relate to nature – in which water plays an important role.

Water resources are abundant in Papua. There are five officially classified main river basins: Kamundan-Sebyar, Omba, Eilanden-Bikuma-Digoel, Mamberamo-Tami-Apavaur, and Wapoga-Mimika. The latter three basins are in five customary zones (Saireri, Mamta, Mee Pago, La Pago, and Ha Anim) and together distribute to 153 watersheds, 15 lakes, and 40 groundwater basins. This means that the majority of Papua Indigenous people either live surrounded by fresh water, along the coastal areas, and/or on small islands. A brief introduction to the water governance practices by three different tribes highlights both their uniqueness and similarities. For example, the Malind Anim occupy both coastal areas and fresh water areas like swamps and riverbeds, and they have their own values to utilise and maintain the areas. The Sambom people meanwhile live in hinterland Papua and have their own ways to support freshwater bodies and thereby their daily life. The Enggros people occupy the Youtefa Bay and retain and care for their mangrove forests (including Tonotwiyat or “women’s forests”) both as a food resource and because of their cultural value.

The Malind Anim

The traditional land of the Malind Anim tribe (also known as the Marind Anim) is the vast Merauke Regency territory on the southern part of Papua, including areas that border Papua New Guinea. This area is characterised by many big rivers over 100 kilometers in length. The Malind Anim’s territory is located alongside the Fly, Mbian, Maro, Bulaka, and eastern Digul rivers, as well as along the coastal areas of the Arafura Sea and Kimaan Island. Most noticeably, the ecosystem influences the names of the Malind Anim, such as Malind Duh (“sea people,” or those who live along the coastal areas), Marind Deg (“river people,” or those who live along the rivers), and Marind Bob (“swamp people,” or those who live inland). This shows that the type of water resources influences people’s identity.

The life of the Malind Anim is also influenced by the monsoon climate, and they have their own concept – based on their lunar calendar – of the east monsoon and west monsoon, which relates to climate and which distinguishes the dry and the wet seasons.

As part of their water governance practices, the Malind Anim have also maintained their traditional cultivation system called wambad [Fig. 1]. The central feature of the wambad system consists of an elevated garden bed that has been dug by people in order to avoid flooding during the wet season. This is complemented by a traditional drainage system called kamahib, the size of which varies depending on the size of the wambad’s yield. The wambad system makes smart use of topography to drain excess water, as these gardens are usually close to a water body such as a tributary river or a swamp. Based on my discussion with an Elder of the tribe, Bapak Isaias Y Ndiken, it can be said that the kamahib traditional drainage system functions as an irrigation system as well. During the monsoon seasons the kamahib absorbs and stores fresh water. During the subsequent dry season, this is used to water the wati, bananas, bitter nut, and other plants that are grown in the elevated garden bed. The wati is an important plant for customary ceremonies and traditional rituals. The kamahib also functions as a habitat for fish, providing a body of freshwater during the dry season. Therefore, the wambad and kamahib features of Malind Anim’s traditional water governance practices provide the community with resilience because they can rely on their own plentiful and high-quality food year round.

While traditional Malind Anim water governance knowledge and practices support their lives and livelihoods, the people also have a spiritual relationship with water. Their worldview includes concepts of the Dema and the totem, and both inform a relationship with water that perceives water to be sacred. Prominent cultural anthropologist Jan van Baal described Dema as spiritual beings who lived in ancestral times and have since experienced metamorphism into nature – animals, plants, and landscape features. 2 For example, one Dema, called Teimbre, changed into reeds and swamp grass after he died in a swamp. Dema can also transform from one shape into another. For example, Ganguta is a tree Dema who used to live in a place called Onggar but exists now in the shape of a tree, whose leaves turn into fish when they fall into the sea. 3 The Dema can especially be found in coastal areas, forests, wetlands, and swamps.

As van Baal noted, particular Dema are also associated with natural phenomena and the universe. 4 So called Yorma is a sea Dema who can destroy any housing with his big waves. Yorma is the son of the two Demas of the depths (called Desse and Dawena) who provide the community with ground water. The moon Dema is called Mandow-kuper Sav. The west monsoon Dema is called Muli, while the eastern monsoon Dema is called Sendawi. Sendawi is the son of Yamiwal, who is the Dema of thunder, and so forth. 5 Because of peoples’ belief in the Dema, they will not change the natural landscape around them. They refrain from draining a swamp, cutting the mangroves, or polluting a sacred water source.

The Malind Anim also adhere to the totem belief system. Totemism concerns the relationship between one clan with a particular plant or animal species or natural phenomenon. Communities who live close to the water often have a totem who lives in the water - a crocodile, a waterlily, big waves, or a particular species of fish. 6 If such a particular species disappears from the area, that means that the identity of that particular clan also ceases to exist. Since the (local) extinction of an animal results in the loss of the clan’s identity, the wellbeing and fate of the local ecosystem is directly related to that of the local community.

Thus while the Malind Anim protect several places for the purpose of securing water supplies – for example, spring water sources (Awamadka) that provide water resources during the long dry season – they also protect stretches of the river and swamps because these are considered sacred places related to Demas or totems who live inside those waterbodies.

The Enggros people

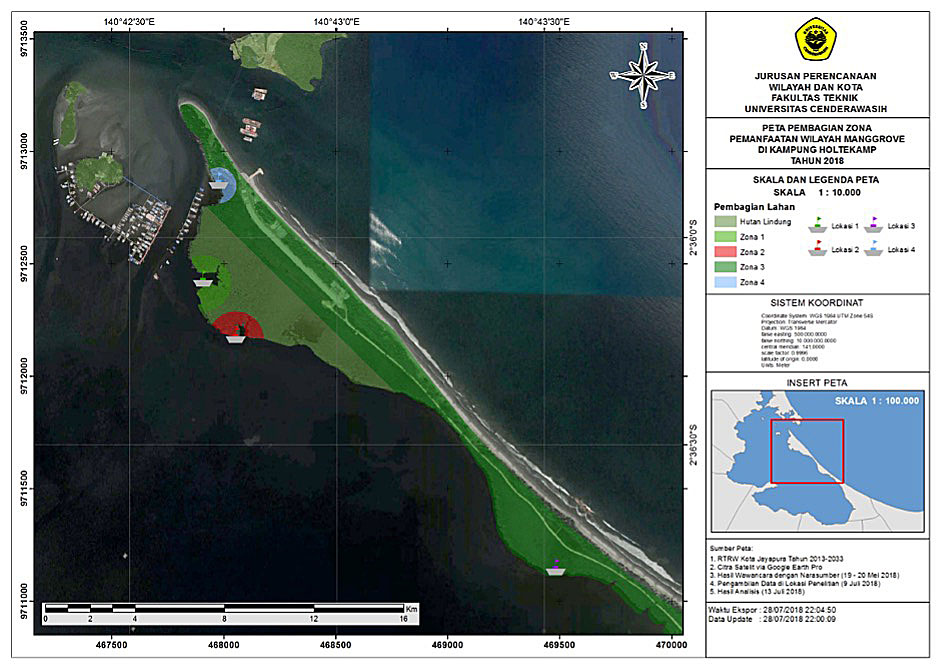

The Enggros people live in Youtefa bay together with the Nafri people and Tobati people. Enggros people build their houses on stilts because they are surrounded by seawater and depend on the nature around them, especially the mangroves. S.W. Taran, a student under my supervision, researched the gender dynamics of their forest governance system in 2018. She noted a number of “gender territories” [Fig. 2] – areas without a physical boundary but which everyone in the community knows can only be entered, monitored, or utilised by either men or women. 7

Fig. 2: The customary zones of the Enggros people. (Map courtesy of S.W. Taran, 2018)

Figure 2 shows that Zone 1 and Zone 2 are customary mangrove forests that function as “women’s forests” called Tonotwiyat. Only women can enter these areas to look for seashells and to fish, socialise, and undress to be comfortable. The women enter these mangrove areas with a canoe and dock the canoe at the edge of a bay as a sign that a group of women are in the area. If a man does enter these areas, he will get customary punishment depending on whether it was accidental or on purpose. The customary punishment is divided into three levels of payment: small (valuable) navy blue beads for intentional entry of an area known to be for women only, green beads as a medium punishment, and brown beads for accidental entry. 8

Contrary to most other areas, which belong to either the Tobatri people or the Enggros people, the mangrove forested Zone 3 is accessible for women from both local tribes who use the area for fishing. Recently, however, Zone 3 has undergone a lot of economic development and some of these customary forests are experiencing reclamation. Zone 4 is utilised by men for providing house-building materials and firewood, but this zone has also undergone a lot of economic development. This economic development has gone hand-in-hand with the diminishing of the mangrove forests.

The Sambom people

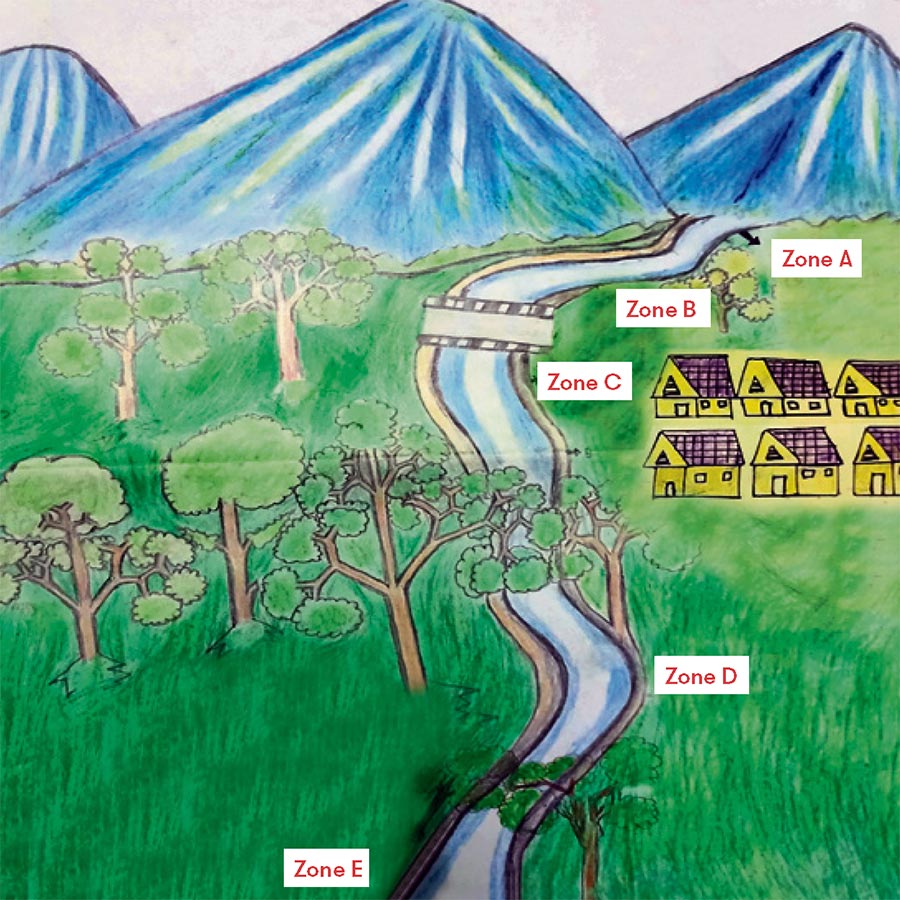

The Sambom people live around Helaksili Village in the Abenaho District of Yalimo Regency. The people of this village use water from Kali Eleli (Eleli River), whose source is in Hawi Mountain, the highest mountain in that district. The Sambom people have their own management system to govern this fresh water source, consisting of a traditional zoning system that for centuries maintained high-quality water in the river. This system benefits the local community as well as wildlife. My student Marice Sambom, a member of the Sambom tribe, conducted research on this zoning system. She identifies 5 different zones, featured in her sketch [Fig. 3]. 9

Zone A [Fig. 5] covers the area of the water spring that flows from Hawi Mountain [Fig. 4]. This is a zone where people preserve the water area as it is. The forest around this zone is kept undisturbed from human activity. The clear part of the river is particularly sacred in the Sambom’s worldview. This is because, historically, the Sambom and Kepno ancestors performed ceremonies and rituals in this area. This zone is forbidden to the public, and only people who “belong” to the river (e.g., the community chief and his family) may enter. The customary punishment for entering without permission consists of payment of either money or a pig. According to local belief, a man entered the forest without permission from an authorised family, got lost due to the punishment of a spirit, and is still endlessly dwelling inside the area. 10

Zone B [Fig. 7] is the location from which people take their drinking and cooking water. People use a small water storage device made from bamboo called findi jagat kecil with which water is taken from the Eleli River to their house. This area is approximately one kilometre away from the community settlement. Zone C [Figs. 8-9] is used for domestic purposes such as dish washing and laundry. Zone D [Fig. 10] hosts the bathing place for men, and Zone E [Fig. 11] is the bathing place for women.

The area between Zones C and D consists of a bush ecosystem covered with rocks and long-leaf plants called Holim Engga. The area between the two bathing places is an effective, densely forested border consisting of big Wile and Evi Alem trees that prevent men and women from reaching each other’s bathing areas.

Fig. 3: Sketch of the five zones of the traditional water governance system of the Sambom people. (Artwork by Marice Sambom, 2022)

Zone A

3.1: A view of Hawi Mountain where the water spring that is sacred to the Sambom is located. People preserve the water area as it is, and the surrounding forest is kept undisturbed from human activity. The clear part of the river is especially sacred to the Sambom. (Photo courtesy of Marice Sambom, 2021)

3.2: The sacred natural site that is at the heart of a traditional zoning system by the Sambom, which for centuries maintained high-quality water in the river. This area is especially sacred since, historically, the Sambom and Kepno ancestors performed ceremonies and rituals in this area. (Photo courtesy of Marice Sambom, 2021)

3.3: A land area that forms part of the sacred natural site. (Photo courtesy of Marice Sambom, Yalimo Regency, Papua, 2021)

Zone B

3.4: View of the location from which the local Sambom community take their drinking and cooking water. (Photo courtesy of Marice Sambom, Yalimo Regency, Papua, 2021)

Zone C

3.5: View of the location where people utilise the river for domestic purposes such as dish washing and laundry. (Photo courtesy of Marice Sambom, Yalimo Regency, Papua, 2021)

3.6: View of the location where people utilise the river for domestic purposes such as dish washing and laundry. (Photo courtesy of Marice Sambom, Yalimo Regency, Papua, 2021)

Zone D and E

3.7: Boys swimming in the part of the river that is accessible to males only (zone D).

3.8: Women taking a bath in the part of the river that is accessible to females only (zone E). (Photos courtesy of Marice Sambom, Yalimo Regency, Papua, 2021)

Conclusion

Different tribes of the Indigenous Papua Peoples each have their own traditional systems to govern water, and these are rooted in their worldviews and cultural values. These systems have for centuries protected the ecosystem, and even today, they help local communities stay healthy. Respectful interaction with the other beings who share the nature around them underlines that Indigenous Peoples’ systems can teach us valuable lessons on conservation, development, and adaptation to the effects of climate change. The traditional cultivation and drainage system from the Malind Anim shows that traditional ecological knowledge benefits the control of flooding during the rainy season and provides food security year round. Moreover, their Dema- and totem-based belief systems effectively conserve nature. Mangrove forest governance by the Enggros illustrates how gender informs human interaction with nature. The traditional zoning system that the Sambom employ shows how sacred sections of the river are effectively setting parts of the river aside for wildlife and ensuring clean water for use by the community.

Fig. 4: Author (right) and interviewee Elder Pak Isaias Y Ndiken (left) in Jayapura City after an interview on the Wambad system. (Photo Charles Wambrauw, 2022)

This article highlights the knowledge and practices by only three out the 269 Papua tribes. The Indigenous knowledge and practices of other Papua tribes contain other unique, time-tested approaches that should be taken seriously in our efforts to address the developmental and environmental challenges of our time, in which both water and justice for Indigenous Peoples are crucial issues. They deserve to be better researched, understood, and respected.

Elisabeth Veronika Wambrauw is the head of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at the Universitas Cenderawasih in Jayapura, Indonesia. Her research focusses on sustainable development and traditional ecological knowledge related to water and infrastructure as well as climate change. Email: elisabethvwbr2020@gmail.com