Sea Changes in the Lives of Japanese Buddhist Women in Hawai‘i

Three cycles of change characterize the evolution of Japanese Buddhist temples in Hawai‘i: the early years, the war years, and the contemporary period. This brief article explores women’s roles and patterns of adaptation to local circumstances over generations during these cycles of change. Special attention is given to the experiences of Japanese immigrant Buddhist women in the Jōdo Shinshū school of Buddhism. The aim is to show how Japanese women who immigrated to Hawai‘i helped shape a uniquely local flavor of Buddhism, made significant contributions to Jōdo Shinshū’s development, and helped ensure the continuity of Buddhist traditions up to the modern period.

Hawai‘i, the world’s largest island chain, is a unique social and cultural crossroads of peoples from diverse ethnic, linguistic, and religious backgrounds. At the time of Japanese in-migration, Hawai‘i was a colonized territory. Because of its colonial history and the incarceration of Japanese American citizens during World War II, awareness of social and political justice issues is relatively high. It took the American government 100 years to formally apologize for its overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893. Successive waves of immigration – Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Vietnamese, South Pacific Islanders, and many others – have made Native Hawaiians a minority in their own land. In response, Native Hawaiian culture exerted a profound influence on immigrants in all spheres of society.

Waves of migration

The Japanese contract laborers who migrated to Hawai‘i toward the end of the nineteenth century largely identified as Buddhists. At that time, Buddhism was the religion of a small minority and it was often misunderstood. Plantation workers felt compelled to hide their Buddhist shrines and Buddha images behind screens to avoid being denigrated as idol worshipers. At first, Christian officials refused to accept the legality of marriages conducted in Japan and couples were required to undergo a Christian wedding ceremony when they arrived in Honolulu. After protests by members of the Japanese community, authorities of the Territory of Hawai‘i conceded and began to allow Buddhist priests to certify marriages. 1

The first wave of Japanese workers endured many unexpected travails: harsh working conditions, abuse by overseers, poor housing, social dislocation, and racial prejudice. The large numbers and perceived “foreignness” of immigrants from Japan aroused fear in the white overlords. By 1920, people of Japanese ancestry constituted 43 percent of the population, arousing fears of a potential “racial menace.” At the time, most spoke only Japanese and preferred the values and customs of their homeland rather than adapting to the host culture. Most planned to return to Japan one day and therefore sought Japanese language education for their children, giving rise to Japanese-language schools in the temples.

Working conditions on the sugar and pineapple plantations were brutal and Japanese immigrant women endured many hardships. To cope with these hardships, and to affirm their cultural identity and heritage, workers and their families began to establish Buddhist temples in plantation communities around the islands. The majority of these temples were affiliated with Jōdo Shinshū, the largest Buddhist denomination in Japan, with both the Higashi Hongwanji and Nishi Hongwanji branches of Jōdo Shinshū represented. On March 2, 1889, the first Buddhist temple in Hawai‘i was established in Hilo by Soryu Kagahi (1855–1917), a Jōdo Shinshū priest from Kyushu, Japan. Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawai‘i oversees the temples of the Nishi Hongwanji branch of Jōdo Shinshū in Hawai‘i and is responsible for communications with Jōdo Shinshū headquarters in Kyoyo, Japan.

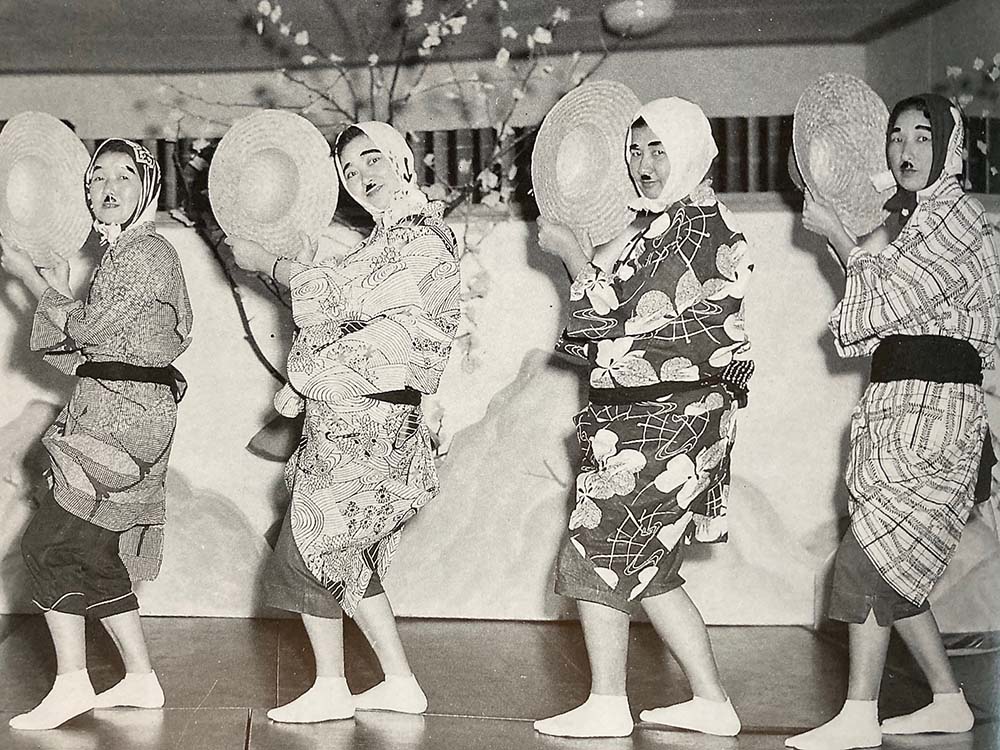

The various schools of Japanese Buddhism share many religious elements and cultural traditions in common. At the same time, the Japanese migrants and their religious leaders sought to uphold the unique heritage and institutional identity of their own particular Buddhist schools as they became acclimatized to their new environment. In the process of settling, adjusting, and adapting to life in Hawai‘i, the immigrants faced many challenges and the Japanese Buddhist temples were in a unique position to help maintain cultural cohesion, facilitate social orientation, and nurture the spiritual life of their members. Plantation workers and their families found community support and spiritual solace at their local Buddhist temples. Buddhist women's organizations called “Fujinkai” (婦人会, Buddhist Women’s Associations) were pivotal in the process of adaptation, creating a sense of community among their members and promoting Japanese culture through their youth groups, chanting groups, tea ceremony and flower arrangement classes, and a host of activities. Fujinkai were founded in all Jōdo Shinshū temples and became influential in connecting and encouraging members who lived on different islands.

The ministers who were sent to Hawai‘i by Honpa Hongwanji headquarters in Japan were not well compensated and their families lived in substandard housing. In Immigrants to the Pure Land, Michihiro Ama mentions that ministers sent from Japan (all male) were quite shocked by the low salary and poor accommodations provided in Hawai‘i, especially in comparison with the high salaries and posh standard of living enjoyed by some Buddhist priests in Japan. 2 The ministers assigned to ministerial posts in Hawai‘i spoke little or no English, which made for difficult communications between the recently arrived Buddhist clergy members and their congregations of plantation workers. Even with limited language skills, they were expected to tend to administrative duties, provide Buddhist education, resolve conflicts, and preside at services in times of illness and death. The wives of these missionaries worked extremely hard and experienced many hardships.

As Buddhism began adjusting to a predominately Christian environment, a process of religious accommodation took place. Pews were installed in place of tatami mats, hymns replaced sūtra recitations, priests became known as ministers, and temples became known as churches, Dharma schools similar to Sunday schools were created for children, and Sunday services structured like Christian services began. The chief incumbent of Honpa Hongwanji, Reverend Emyo Imamura (1867–1932), made a conscientious effort to modernize Buddhism, using Christian churches as a model. Alongside ethnic Japanese elements, he introduced English services, wrote Buddhist hymns, and carefully promoted adaptation to the American context. Working with Ernest Shinkaku Hunt (1878–1967), an Anglo American Buddhist who ordained as a Hongwanji minister, Imamura implemented Sunday schools and a Young Buddhist Association, among other innovations. Consciously adopting the Christian model for religious services and other activities was seen as a skillful means of making Buddhism more socially acceptable. The struggling Japanese Buddhist community felt validated and greatly encouraged by the well-publicized presence of Queen Lili‘uokalani at a ceremony commemorating the birth of Shinran Shonin held on May 19, 1901. 3

Several sources mention the early history of Fujinkai in temples in Hawai‘i. A very useful and perhaps the most complete source is Hōsha: A Pictorial History of Jōdo Shinshū Women in Hawaii, a commemorative volume compiled by Jōdo Shinshū women themselves. 4 The book summarizes the establishment, development, activities, and the status of 36 branches that existed in 1989, when the book was published, and includes many historical photos. Toku Umehara, president of the Buddhist Women’s Association from 1976 to 1978, expressed the goal that motivated the project: “The youth of today will truly come to understand the unselfish devotion, whole-hearted dedication and humble services rendered by the pioneer Fujinkai women in their endeavor to uphold their temples as well as their organizations.” She refuted a persistent impression that the organization was simply a women’s social club, saying that “Fujinkai organizations are unique in that they are religiously oriented, rather than primarily social organizations.” Her hope was that Fujinkai members make the most of every opportunity to listen to the Jōdo Shinshū teachings and become role models for young people so “they will be able to understand that we are always surrounded by the Wisdom and Compassion of Amida Buddha.” This sentiment is also reflected in her Jōdo Shinshū perspective on monpō (聞法), or “listening to the teachings sincerely and gratefully”: “By listening we come to realize that as human beings we cannot escape our own earthly greed and passions. The knowledge of our powerlessness leads us to entrust ourselves to Amida Buddha and his Primal Vow.... Our first and foremost responsibility as Fujinkai members is to make every effort to listen to the teachings.”

Fig. 2: Fujinkai members bond through cultural activities, including Japanese dance. (Photo courtesy of The Hawaii Federation of Honpa Hongwanji, 1989)

Fujinkai in Hawai‘i was initiated by Reverend Honi Satomi (1853–1922), the first bishop of the Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii, in 1889. Bishop Emyo Imamura formally established the organization in 1903 and his wife Kiyoko Imamura was elected to be the first president in that same year. 5 Under her leadership, Fujinkai members became active in social welfare work, sporting events, hospital visits, and other community service projects. Women’s active engagement in the earliest stages of the Hongwanji mission is documented in a photo taken at the groundbreaking ceremony at Honpa Hongwanji Betsuin (Headquarters) in Honolulu in 1916. Photos show Fujinkai members wearing matching kimono for the occasion [Fig. 1]. Once the construction of Betsuin was completed two years later, it served as a convenient location for many Fujinkai activities, which included Dharma talks, Sunday school classes, New Years’ celebrations, funeral services, and a range of social service activities. Fujinkai members gathered to commemorate the founding of Hawaii Hongwanji and organized the 700th Memorial Anniversary of Shinran Shonin (1173–1263), the founder of Jōdo Shinshū. Over the years, they organized many fundraising drives to help renovate the temple and construct a designated Fujinkai Hall, which was completed in 1964. Fujinkai members of branch temples were equally active; for example, they organized fundraising for reconstruction after the Hongwanji temple and priest quarters in Pearl City burned down in 1936. Despite their economic limitations, Fujinkai women were dedicated to supporting charitable activities whenever needed.

The principles of Fujinkai are expressed in the Buddhist Women’s Pledge new members recite when they become members: “As a person of Buddhist faith, I will follow Shinran Shonin who sought to live the life of truth; appreciate fully the blessing of human existence; thoroughly hear the Primal Vow of the Buddha; and diligently strive to live the Nembutsu as a Buddhist woman. Earnestly listening to the teaching, I will live my daily life embraced in Amida’s Light. Building a home fragrant with the Nembutsu, I will nurture a child of the Buddha. Following the teaching of ‘One World,’ I will spread the circle of Dharma friends.” 6

Their aspirations and commitment to Buddhist ideals are also expressed in the stated objectives of the Hawaii Federation of Honpa Hongwanji Buddhist Women’s Association: “To unify, assist, and cooperate with all United Hongwanji Buddhist Women’s Associations in the State of Hawaii. To assist in the perpetuation and expansion of Jōdo Shinshū (Pure Land Sect) in the State of Hawaii. To assist in the establishment, progress, and development of Buddhist women’s organizations in the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii. To plan for the advancement and promotion of Buddhism throughout the world, both as a movement and as a way of life. To cooperate with the Buddhist women’s organizations of the world and coordinate activities through active participation, and work for world peace.” 7

The friendships Fujinkai members developed during the early years helped them endure the hardships of plantation life and their Jōdo Shinshū faith provided principles and inspiration that guided their daily lives.

Being Buddhist in a time of war

The Japanese Buddhist community in Hawai‘i suffered further hardships during World War II. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 led to the immediate forced relocation and incarceration of approximately 120,000 Japanese throughout the United States, including citizens and permanent residents. Internees who were still alive in 1988 received a formal apology from the United States government and a pittance in reparations, but the effects of this unconstitutional incarceration have still not been fully recognized.

The war years affected everyone in Hawai‘i, but especially residents and citizens of Japanese extraction. Japanese Buddhists and Christians, young and old, experienced the times differently, depending on their social status, educational background, language ability, and religion. While many factors determined how people of Japanese descent were treated during WWII, those who were more closely one associated with Buddhism were considered more suspect. Even before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, in 1936, President Roosevelt backed a plan to investigate the loyalties and extent of assimilation of Japanese Buddhists in Hawai‘i, California, and elsewhere intended to identify “dangerous” and “potentially dangerous” individuals. When the FBI and ONI (Office of Naval Intelligence) conducted their study, they concluded that Buddhists were more likely to identify with their Japanese ancestry and resist Americanization than their Christian counterparts. 8

Duncan Ryūken Williams has conducted extensive research on the role of religion in the forced relocation and incarceration. He found that many Japanese language teachers and Buddhist priests in Hawai‘i were immediately arrested and sent, without trial, to special detention camps on the mainland for indefinite incarceration. He observes that no Christian ministers were among those detained. 9 Ryūto Tsuda, a Buddhist nun and U.S. citizen born on the island of Hawai‘i, was was one of over 2,000 people of Japanese descent who were arrested because they were suspected of being a national security threat. In contrast to the mainland U.S., where more than 110,000 people were confined due to Executive Order 9066, mass detentions were not feasible in Hawai‘i, where more than one-third of the population had Japanese ancestors. The Geneva Convention bans forced labor and guarantees freedom of religion but these statutes were frequently transgressed or ignored in the camps. 10

Just as Japanese Buddhists suffered more than Japanese Christians, Japanese women experienced more hardships than Japanese men. The vast majority of those incarcerated were men due to the fact that the detainees were mostly priests, Japanese language teachers, and prominent business leaders, typically male. The story of Tomo Izumi is an example of how the detentions left families without economic support and counsel. Her father, Kakusho Izumi, an ordained Jōdo Shinshū priest and Japanese language teacher, was summarily arrested on the night of December 7, 1941, leaving their mother and six children alone at the Papaaloa Hongwanji Mission on the island of Hawai‘i. When he was arrested, he put on his clerical robes and went with his wife and children to the temple and then to the family altar to make prayers. Unbeknownst to his family, he had performed his own funeral rites, expecting to be shot and killed that night. Uncertain where their kind and cheerful father had been taken or what fate awaited them created great fear and confusion in the children and their mother. As it turned out, he was among tens of thousands who were incarcerated based on their Japanese heritage and required to carry Enemy Alien Registration Cards, with their photos, at all times. During this time, reciting the name of Amida Buddha (nembutsu) to be reborn in his Pure Land brought great consolation but the arrests of Buddhist clergy were a great loss to their families and communities, depriving them of guidance and religious leadership. During the clergy’s absence, temple wives or Fujinkai members stepped in to perform funeral rituals and other services with great kindness. Their faith in the saving grace of Amida Buddha helped Jōdo Shinshū followers cope with their grief, anxiety, and personal losses, but the detention of Buddhist priests and the shuttering of Buddhist temples in Hawai‘i surely contributed to a decline in active temple participation.

Reflections at a crossroads

The contributions of Fujinkai members as pioneers in the founding of Jōdo Shinshū temples and as humble, diligent workers dedicated to the perpetuation of these temples is well-recognized in Japanese Buddhist circles. Yet, although Japanese Buddhist women’s selfless dedication in supporting the temples has always been appreciated, their efforts have not always been publicly acknowledged or rewarded, especially by their male colleagues. In the early history of Jōdo Shinshū, women may have preferred to work behind the scenes but that began to change as women became more educated, more confident, and more qualified to take leadership roles in the temples. In the early years on the plantations, women had many responsibilities and were busily engaged in both nurturing their families and working in the fields. Consequently, they usually dedicated their efforts to their local temples and communities. In recent years, however, as their horizons have expanded, Buddhist women have begun making contribution on the statewide, national, and international levels. An example is the student exchange program Fujinkai initiated in 1971 that chose two young women, Gail Mamura and Jan Aratani, as the first students to visit Japan. Another example is Project Dana, a volunteer organization founded in 1989 by Shimeji Kanazawa and Rose Nakamura at Moiliili Hongwanji that provides care for the frail and elderly. This project expanded into an alliance of more than thirty churches and temples to train compassionate caregivers for the community, gaining national recognition for the selfless service of its volunteers. Project Dana models cross-cultural understanding and compassion by providing care for people regardless of their ethnic identity or religion, cooperating with Christian churches and Vietnamese Buddhist temples, and recruiting volunteer caregivers from different religious backgrounds. 11 The success of Fujinkai members in building this interfaith coalition demonstrates the enormous potential of Jōdo Shinshū women for social transformation.

Writing in 1989, Toku Umehara, then president of the Hawaii Federation of Honpa Hongwanji Buddhist Women’s Association, expressed the hope that women would become more active and prominent in Jōdo Shinshū overall: “I expect the image of the Fujinkai members to change as women are becoming educated and they will become important members of the temples. Undoubtedly, we shall see more women as officers of their respective Kyōdan [administrative bodies].” 12 In 1975, while Umehara was president, Fujinkai’s membership grew to 6,400 women. She recognized the social importance of Fujinkai organizations and encouraged women to become more involved in the administrative functioning of the temples, but emphasized that the religious practice of nembutsu was primary. She urged Fujinkai members to serve as examples to the youth by nurturing their spiritual development, listening to Jōdo Shinshū teachings at every opportunity, and surrounding themselves with the wisdom and compassion of Amida Buddha. The biggest question that faces Jōdo Shinshū and other Japanese Buddhist temples today is whether the younger generation of women in Hawai‘i will have the same level of commitment as earlier generations of Fujinkai women did.

Recent changes in Jōdo Shinshū institutional structures are aimed not only at preserving members’ Japanese Buddhist heritage but also at promoting its growth and development, especially among the younger generation. In a time of great social and technological changes, the goal of revitalizing traditional religious structures is not easy to achieve and requires new insights and innovative leadership. In recent years, women have been taking expanded roles in the overall functioning of the temples, not just on the periphery or in the kitchen. Women have become recognized for their leadership skills and are becoming more visible as teachers in Jōdo Shinshū temples, some taking ordination as ministers. Coincidentally or not, during these years, Fujinkai membership and participation have declined and some branches have closed or merged. Some speculate that, as women take more visible roles in temple leadership overall and become more active in religious forums throughout the islands, there will be less need for Fujinkai branches as separate, independent organizations.

The formation of Fujinkai in 1889, concurrently with the founding of the Hawai‘i branch of Hongwanji, can be seen as a momentous achievement for Japanese immigrant women in Hawai‘i. By steadfastly asserting their Japanese Buddhist identity in the face of religious domination by the Christian majority, regardless of the political and social costs, Buddhist women in Hawai‘i made a powerful statement of religious integrity and independence. Successive generations of Jōdo Shinshū women weathered many changes – racism, communications gaps between first-generation (issei, 一世) parents who spoke Japanese and their second-generation (nisei, 二世) children who spoke English, cultural gaps between maintaining Japanese cultural identity in an overwhelmingly Christian environment, living by Buddhist values in a rapidly changing, secularizing social landscape, smaller families and greater employment opportunities – monumental changes that challenged the traditional Jōdo Shinshū worldview.

It can safely be said that the strong ties that earlier generations of women felt to their Japanese heritage and their reliance on temple activities for social networking and cultural enrichment have weakened. A substantial number of young women in Hawai‘i have moved away or drifted away from the temple and may only return for special occasions. Women today have far more options to choose from and many are content to celebrate their Japanese Buddhist heritage by attending Obon Odori (dancing) in late summer or mochi-making at New Year’s. Events such as Obon, traditionally organized at Buddhist temples to honor deceased relatives and ancestors, are opportunities for temple members and friends to come together to celebrate their Japanese cultural identity. Temple leaders are very concerned to reach out to the younger generation and are exploring programs to attract a new digital generation. Increasingly, the English term, Buddhist Women’s Association (BWA) is being used more frequently than Fujinkai, the organization’s original name in Japanese, which most Japanese Americans do not speak. Changes such as this reflect the changing ethos and the need to update and expand the temple’s outlook and membership. Some temples are even adding meditation, taichi, gardening, and Buddhist studies classes to appeal to a new demographic. Whether these innovations will succeed in sparking interest in a new generation of Buddhist women is now in the merciful hands of Amida Buddha.

Karma Lekshe Tsomo is a professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of San Diego. Her research interests include women in Buddhism, Buddhist feminist ethics, death and dying, Buddhism and bioethics, and Buddhist transnationalism. Email: tsomo@sandiego.edu