Representing Arthur Gunn: Popular Music, "American Idol," and Imaginaries of Nepal

In the autumn of 2019, Arthur Gunn stood before three celebrity judges – Katy Perry, Lionel Richie, and Luke Bryan – hoping to become a contestant on the 18th season of ABC’s hit singing competition American Idol. Over the subsequent months, he became a favorite of judges and fans alike with his soulfully belted covers of folk, pop, and reggae songs. He would ultimately win second place in the competition during the season finale in May 2020. Born Dibesh Pokharel, Gunn was raised in Nepal, and this heritage was a prominent storyline for the producers of American Idol. It was also a prominent storyline for the thousands of Nepalis viewing his success from Nepal and around the world. However, these two viewing publics contextualized and interpreted Gunn/Pokharel very differently. This article explores the production of two divergent imaginaries of a singular artist, imaginaries that were based on distinct webs of semiotic relations within which Gunn was placed and understood. At its core, the divergence revolved around the nature of Pokharel’s relationship to his native Nepal – or, even more precisely, how different imaginaries of “Nepal” produced different conceptions of Arthur Gunn.

For the most part, American viewers indexed Gunn by placing his native Nepal in contradistinction to rural America, building a narrative redolent with American Dream mythologies. Meanwhile, Nepali viewers indexed Gunn by situating him within a different constellation of cultural signifiers and historical relations: Kathmandu’s rich musical history, diasporic Nepali cultural productions, emergent 21st-century iterations of Nepali identity, and more. While the latter was a more accurate picture, in both cases the significance of Arthur Gunn/Dibesh Pokharel – that is, what he represented and symbolized to different audiences – depended to a large degree on how “Nepal” itself was imagined and mobilized.

American Idol, American Dream

Throughout his time on American Idol, Gunn’s Nepali heritage was conspicuously featured by the show’s producers and judges. This in itself is unsurprising, since American Idol has a longstanding practice of framing contestants within American Dream narratives. 1 Plenty of other contestants are framed in terms of overcoming adversity: Just Sam, who beat out Gunn in the finale to win Season 18, came from a background singing in New York subway trains, as the show constantly reminded its audience. Gunn/Pokharel, however, appeared custom fitted for a specific archetype of the storyline: the striving immigrant who overcomes humble roots – not only “rags to riches,” but also “there to here.” More precisely, he could be made to fit that storyline, given most viewers’ limited knowledge of Nepal. This American understanding portrayed Gunn as an inspiring example of immigrant assimilation and the American Dream.

Fig. 1: Arthur Gunn auditioning for the celebrity judges of American Idol. (Screenshot from YouTube. Original video property of ABC and American Idol)

Gunn rose to renown on the strength of his regional audition, and a promotional video package – which included a brief interview and sleekly produced montage – garnered millions of views on YouTube [Fig. 1]. 2 It begins with the artist introducing himself: “My name is Dibesh Pokharel, and I go by the stage name called Arthur Gunn.” His accented voice continues over picturesque images of Nepal: drone shots of temples and courtyards, doves congregating around a famous stupa, Tibetan singing bowls, robed monks, distant figures walking mountain trails. The editing of the video reinforces an array of longstanding Western fantasies about Nepal – a place defined by exotic cities and awe-inspiring mountain landscapes, humble traditionalism and intrinsic spiritual wisdom. In other words, the video portrays Nepal as both geographically and culturally remote from America.

Gunn describes his longstanding love of music and explains that he moved to America after high school “because it’s the land of great opportunity.” The next shot: Dibesh and his family in front of their house in Wichita, Kansas, adorned in traditional Nepali garb. Towards the end of the video introduction, he explains that Wichita exposed him to bluegrass and country music and that American Idol is “a chance to make my American dream come true.” Even before Arthur Gunn sang a word, then, the show had effectively curated a particular perspective. It cultivated a precise story by positioning him in relation to a specific set of culturally coded images and Orientalist narratives.

The audition itself begins with Arthur greeting the judges with a “Namaste,” which Katy Perry gleefully returns. When the pleasantries are over, the 21-year old Gunn begins fingerpicking his acoustic guitar and singing a gravelly rendition of Bob Dylan’s classic “Girl from the North Country.” The judges seem taken but request a second tune. Gunn responds with a belted version of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Have You Ever Seen the Rain?,” which would go on to become his signature cover throughout the competition. The judges appear instantly impressed. When he hits the refrain, Katy Perry beams while Luke Bryan and Lionel Richie high-five. In the discussion that follows, Gunn explains that he first auditioned at an open call, when the show brought its bus to Wichita, Kansas. Perry responds: “So you just brought your guitar, you came to the bus, and you sang your song.” Gunn affirms. “I like it,” she says, followed by Luke Bryan: “I mean, what an American story. This is in the middle of Kansas!” Moments later, Lionel Richie physically embraces Gunn, saying, “You are the story we need to tell, and welcome to the world, my friend.” The clear impression was one of delighted surprise on the part of the judges: How could a kid from Nepal sing Bob Dylan and Creedence Clearwater Revival so beautifully?

Subsequent episodes of the show relentlessly reinforced this perspective and emphasized Gunn’s heritage. Thus, the show built a clear narrative around Gunn: a Nepali kid who discovered American roots music in Wichita, a bright-eyed immigrant chasing his own American dream of rock stardom. This portrait was meant to be inspiring precisely because of the imagined distance, both geographical and cultural, that Gunn was supposed to have traversed on his road to success. The show’s judges, promotional videos, and strategic editing all framed Gunn as an embodiment of immigrant dreams and cultural assimilation. None of this denies Gunn’s formidable musical talent. However, the not-so-subtle storyline presented by American Idol viewed this talent as especially exceptional given Arthur Gunn’s identity and heritage.

For both Americans and Nepalis, “Nepal” was a critical signifier in the web of semiotic relations through which Arthur Gunn was interpreted. American Idol – and presumably the show’s American audience as well – composed a particular (and particularly provincial) image of Gunn. Continuing a longstanding interest in presenting “inspiring” stories, the show presented Dibesh Pokharel as a humble Nepali kid with big dreams, an intrepid youth who made his way to Kansas and discovered American roots music. This portrayal relies upon, and dovetails with, tired Orientalist fantasies about Nepal as intrinsically remote, exotic, traditional, underdeveloped, spiritual, rural, and un-/pre-modern. Kansas, the archetypal embodiment of Middle America, becomes the agent of transformation and opportunity, the cultural geography that broadened Gunn’s musical horizons and opened new professional doors. By this interpretation, the webs of meaning composing Arthur Gunn all but require a humble origin story in an exotic, non-Western place. Nepal, at least as imagined by many Americans, seemed to fit the bill.

The delight with which the judges evaluated Gunn, his substantial talent notwithstanding, stemmed to some extent from their surprise at his virtuosity with Western music. In part, this presumes that Nepalis lack a connection with such genres. It implicitly suggests that Gunn was a wonderful folk singer and guitar player notwithstanding his Nepali origins. On the season finale in May 2020, Arthur Gunn played yet another arrangement of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Have You Ever Seen the Rain?” The same B-roll of South Asian mountains, monks, and temples introduced his performance. After the song, Luke Bryan said, “If there are any more like you in Kathmandu, please get on the phone and call them and tell them to come out next year. Please!” The other judges laughed amicably, and Lionel Richie chimed in: “So true!” Our point is not to disparage the American Idol judges, but rather to highlight the central importance of their imaginaries about Nepal for how they made sense of Arthur Gunn.

The transnational lineages of Nepali music

Bryan’s comments resonated quite differently for the thousands of Nepalis around the world who were following Gunn’s success. For those familiar with Kathmandu and the Nepali diaspora, Arthur Gunn was not an anomaly at all, except insofar as he broke through to global fame. Indeed, the irony of Bryan’s comment is that Kathmandu is filled with talented young musicians proficient not only in “traditional” Nepali genres, but also in rock, folk, blues, jazz, reggae, fusion, heavy metal, and hip-hop. Kathmandu’s music scene is teeming with diverse artists, all of whom embody long histories of mobility and transnationalism that link Kathmandu with the world beyond. When Bryan asked if there are any others in Kathmandu, Nepalis around the world laughed not because there are not, but because it seemed patently obvious that there are. From the beginning, Nepali viewing publics situated Arthur Gunn not within narratives of cultural assimilation and the American Dream, but within long histories of musical creativity in Nepal and across the Nepali diaspora. On the one hand, Arthur Gunn was placed in relation to a different set of signifiers, such that “Kansas” decreased in explanatory importance. On the other hand, the assemblage of “Nepal” was still crucial, but its particular meaning was shifted.

Nepalis, both inside Nepal and around the world, actively followed Arthur Gunn’s success on American Idol. When his audition video began spreading in early 2020, Nepalis watched, circulated, and discussed it widely and eagerly. There was, to be sure, a certain degree of hometown pride and vicariousness in such viewing. There may even have been a bit of American Dream mythology among some. By and large, though, Nepalis did not understand Gunn as an exception to the modern Nepali music scene, but rather as a direct descendent of it. Gunn was not a wonderful folk-rock musician despite coming from Kathmandu, but because he came from Kathmandu. Nepalis had a different set of cultural and historical touchstones through which to make sense of Gunn: the long history of rock n’ roll in Kathmandu, spaces of rich (sub)cultural production, and diasporic circulations to places like Hong Kong and London. This was the idea of “Nepal” within which many Nepalis understood Gunn’s style – not a landscape of remote mysticism, but a real place. This yielded a different “Arthur Gunn” altogether, one who embodied and reflected a different set of geographic, cultural, and historical imaginaries.

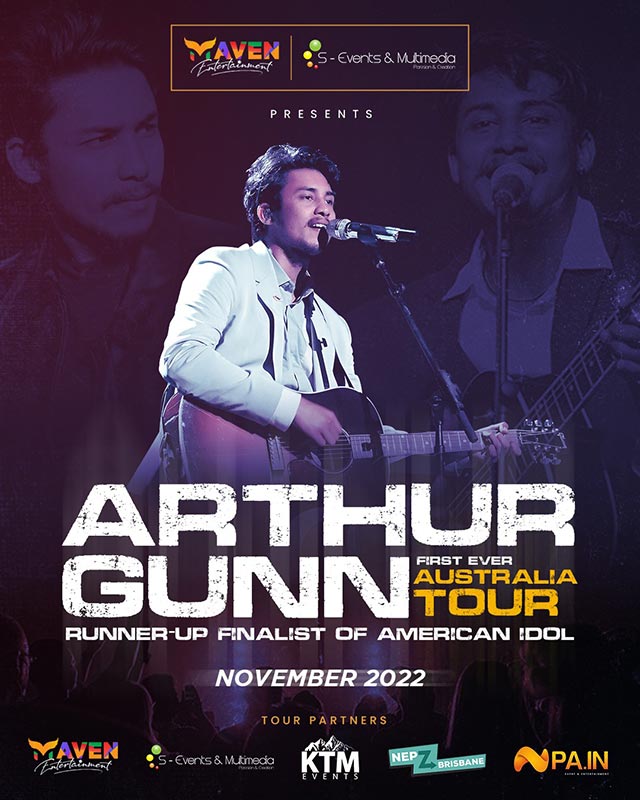

For us authors, Gunn immediately evoked not imaginaries of Kansas and rural Americana, but the cosmopolitan cultural spaces of Kathmandu and Nepali enclaves abroad [Fig. 2]. Arthur Gunn moved to Kansas after completing his schooling in Nepal. For the American viewing public, this displacement is a crucial chapter for framing Arthur Gunn’s affect and musical style. His music, by this logic, is rooted in American lineages of folk, roots, and rock. Nepal becomes the foil, the origin point from which Gunn had to move outward in order to encounter Bob Dylan, John Denver, and Creedence Clearwater Revival. There is a familiar politics of authenticity at play, whereby “authentic” Nepal cannot explain such music being performed by Arthur Gunn, but “authentic” America can. Such perspectives reveal the way in which Western imaginaries of South Asia obfuscate popular music history in Nepal.

Fig. 2: Promotional poster advertising Arthur Gunn’s recent tour of Australia. (Image courtesy of S-Events & Multimedia, 2022).

Even if Arthur Gunn fortified his interest in country and bluegrass music after moving to Wichita, his musical stylings were clearly forged in relation to music scenes in Nepal as well. Dibesh Pokharel had already begun playing music before setting foot in the United States. Even after he moved to Kansas, he returned to play shows in some of Kathmandu’s well-known venues. In 2018, he released his debut album Grahan, a collection of original songs with Nepali lyrics. He has played shows in Thamel and Jhamsikhel, two neighborhoods imbricated in an array of socio-spatial contestations that seek to expand the acceptable parameters of Nepali identity through new modes of consumption and cultural practice. 3 In 2022, he returned to Nepal once again on a “Homecoming Tour.” Music has been, and remains, a pivotal medium through which Nepalis perform, contest, and reshape personal and national identities.

From the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries, Nepal was ruled by the autocratic Rana family, hereditary prime ministers who imposed strict sumptuary laws that effectively isolated most Nepalis (though not the Ranas themselves) from foreign goods and media. 4 In 1951, the monarchy under King Tribhuvan reasserted power and wrested de facto control of the state back from the Ranas. What followed is generally presented as a period of radical “opening up” after a century of relative enclosure and disconnection from the outside world. New media and foreign tourists began entering Nepal and broadening its musical horizons. The influence of Western styles on Nepali pop music began in the 1950s, in no small part due to the instantiation of Radio Nepal in 1951. 5 Meanwhile, Nepal became accessible to foreign tourists. Initially, these foreigners were mountaineers or elderly elites seeking a new prestige destination. By the late 1960s, however, Western countercultural seekers (i.e., hippies) had begun arriving in Kathmandu via overland bus routes, drawn by their own array of Orientalist fantasies to a place where marijuana was then legal. 6 The British folk icon Cat Stevens famously visited Nepal during this period. They brought new music, new fashions, and new ideas, and these were appealing to many young Nepalis. To this day, musicians beloved by global hippiedom – Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan, and Bob Marley – remain classics in Kathmandu.

As Nepal opened itself up to foreigners in the second half of the 20th century, it also invited teachers, writers, artists, and musicians from its older diasporic communities in Darjeeling and other parts of Northeast India. Musicians from these places helped establish some of the earliest rock bands in Nepal, including Prism and 1974 AD. Many such bands continue to receive adoration to this day. Simultaneously, Gurkha soldiers who made up exclusive Nepali regiments within the British Army brought with them cassette tapes picked up from places they were stationed around the world.

The 1990s were yet another watershed moment in the cultural history of Kathmandu. Since the 1960s, Nepal’s political system was a pseudo-democratic Panchayat system of rule, which generally stifled diversity in favor of a hegemonic national identity, defined narrowly as the culture of high-caste Hindu elites. This ended after popular protests known as the Jana Andolan (People’s Movement) demanded substantial political reforms in 1990. What followed was a wave of constitutional experiments, economic liberalization, and decreased media censorship. A consumerist middle class emerged in Kathmandu, and along with it new social categories of youth and their attendant practices. 7 By the late 1990s, a civil war between state forces and Maoist insurgents had begun driving many rural villagers into Kathmandu, dramatically diversifying the cityscape and its demography. The relevant upshot of this (very truncated) history is that young people in 1990s Kathmandu were socialized and enculturated into dramatically different lifeworlds from previous generations. New media, from the Sunday Pop radio show to print magazines like Wave, encouraged and shaped emerging cultural identities defined by non-traditional dress styles, fashions, and music.

These cultural transformations manifested spatially in Kathmandu. Early rock bands in Kathmandu tended to perform where the foreigners were: on the one hand, the few swanky hotels favored by wealthy tourists; and on the other hand, the dingier cafes and flophouses of Jhochhen/“Freak Street” favored by the hippies. By the late 80s, the formerly peripheral neighborhood of Thamel had overtaken these old spatializations by catering to a middle-class tourist demographic interested in the burgeoning attraction of “adventure” and “trekking” tourism. Pubs and restaurants in the neighborhood blasted popular music, and more live bands formed to play gigs in Thamel. As the tourist hub migrated to Thamel, in other words, “music moved with it.” 8 While bands performed in other spaces and contexts around the city, Thamel became a magnet attracting musicians and groups interested in all manner of “foreign” genres. Prominent among these were reggae, psychedelia, classic rock, grunge, and 80s metal. These days, in any Thamel bar, on any given night, practically any set list will include some combination of standard staples evoking this history: Bob Marley and Pearl Jam, Pink Floyd and Bon Jovi, Creedence Clearwater Revival and Kings of Leon. These staples further inscribed themselves as Nepali musical heritage as they were – and continue to be – reproduced through live covers at diasporic music events in pubs, bars, community centers, and concert halls around the world. They also became important canons in the transmission of musical knowledge, serving as templates for the production of rock music amongst Nepalis, despite the evolutions embracing musical genres such as rap, R&B, and Lo-Fi.

Fig. 3: A rock show in the popular Kathmandu music venue Purple Haze. (Photo by Benjamin Linder, c. 2017)

The transformative 1990s in Kathmandu produced a young generation of urbanites whose subjectivities were not only forged in relation to a different set of structuring inputs, but who were increasingly able to partake in a variety of new practices and tastes. This prominently included music. Many of the bars in Thamel these days rely on Nepali consumers far more than foreign customers. The rollicking rock shows in clubs like Purple Haze, Reggae Bar, or Shisha Terrace are frequently catered not to foreigners fresh off their mountain treks, but to hordes of shouting Nepalis eager to sing along with any number of Thamel standards [Fig. 3].

This is why, in 2020, it came as no surprise to see an overseas Nepali performing songs like “Have You Ever Seen the Rain?” and “Is This Love.” The global recognition and degree of success may have been new for Nepal, but Creedence Clearwater Revival and Bob Marley certainly where not.

A tale of two Nepals

American Idol curated Arthur Gunn through a particular set of semiotic relationships. For American audiences, Gunn’s relationship to the American heartland, American Dream mythologies, and immigrant assimilation narratives all occupied nodal roles in signifying the artist. These factors played a far more minor role in the dominant interpretations by Nepali viewing publics. For young Nepalis, Gunn evoked the cosmopolitan, sub-cultural spaces of Kathmandu at least as much as he evoked the cornfields of Kansas. For the diaspora, Arthur Gunn reminded them of the sounds and places they grew up with and returned to when visiting “home”: the live music venues of their youth that continue to play the same beloved songs to newer generations. The sound of home is “Hotel California” by the Eagles, blasting through someone’s window above the bells and rickshaws weaving through the bustling streets of Kathmandu. From the English countryside to the streets of Melbourne, Nepalis arranged concert tours for Arthur. For them, Arthur sang the songs they had always sung.

“Nepal” – not as a geographic territory, but as a cultural idea – is the lynchpin in all of this. American Idol presented a narrative of Arthur Gunn that necessitated a particular image of Nepal: remote and exotic, humble and spiritual. That image, of course, is fed by an obdurate wellspring of Orientalist tropes and Western projections. At best, it presents a highly selective impression of Nepal; at worst, it reiterates tired imperial discourses that have long relegated Nepal to the global margins.

Young Nepalis, especially urban Nepalis, are significantly less vulnerable to these imaginaries. Kathmandu is simply not reducible to such Western fantasies. It is a lived-in reality. Importantly, this actually existing Nepal embodies histories of transnationalism through the mobility of incoming foreign tourists, outbound laborers, educational migrants, and diasporic Nepalis overseas. Such transnational movements have always had a substantial cultural dimension to them. Indeed, the development of Kathmandu’s thriving and diverse music scene emerged out of these itineraries. 9 Their sounds were produced from circuits of travel and migration, the meeting point of routes from hippies and travelers, trails from tea plantations in Darjeeling and roads lit by night markets in Hong Kong.

Arthur Gunn/Dibesh Pokharel reflected a set of entangled histories and cultural geographies. In some sense, the “Nepal” that one imagines determined the “Arthur Gunn” that one witnessed. Contra dominant narratives proffered by the producers, judges, and audiences of American Idol, Gunn is a clear manifestation of contemporary Nepal and its recent decades. He has not transcended the cultural world of Kathmandu; he has distilled it. His musical style does not negate his Nepali roots; it embodies them. The bifurcation of Arthur Gunn into two discrete narratives, then, reignites persistent questions of representation and authenticity. In short, it indexes a larger struggle over the meaning, imagination, and reality of Nepal itself.

Benjamin Linder is an anthropologist working as the Public & Engaged Scholarship Coordinator at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS). Email: b.linder@iias.nl

Premila van Ommen is a PhD candidate in Cultural Studies at the University of the Arts, London, exploring Gurkha heritage and Nepali youth cultures in the United Kingdom. Email: heliosphile@gmail.com