Olympic Dreams and Traumata: Looking Back at Tokyo 2020

On 8 August 2021 at 10.19 p.m. local time, the Olympic flame was extinguished in the new National Stadium in Tokyo. This marked the end of historic Games: the first time ever that they were postponed for a year, and the first time ever that they were held (almost) without live spectators. The fact that Tokyo is also the first city in Asia to host the Games twice was eclipsed by the pandemic, as were Tokyo's and Japan's original ambitions to repeat the success and emotions of Tokyo 1964. Back then, Japan had impressed the world with, among other things, the high-speed Shinkansen bullet train, live satellite broadcasting, and its unbeatable women's volleyball team. Those Games had injected new self-confidence into its nation after the destruction, defeat, and isolation left in wake of World War II.

The myth of zero risk Games

"1964 once again" was one of the mottos with which the organizers wanted to get the Japanese into the Olympic mood since the successful bid for Tokyo 2020 in September 2013 [Fig. 1].1 In the midst of the pandemic, however, the references to the first Summer Olympics in Asia 57 years ago were of less interest than the daily updated infection figures in Tokyo and all of Japan: there were 1359 (Tokyo)/4223 (Japan) new infections on the day of the opening ceremony, and this number more than tripled to 4066/14472 by the day of the closing ceremony 2 Shortly before the start of the Games, Tokyo had extended its state of emergency. On the day of the closing ceremony, a state of emergency was in place in six prefectures, with a quasi-state of emergency in 13 others. The 7-day incidence per 100,000 inhabitants on the closing day was 196 in Tokyo. In Tokyo's neighbouring Olympic prefectures, this number had risen to 126 in Kanagawa (sailing, baseball, softball, football), to 106 in Saitama (football, basketball, golf), and to 100 in Chiba (surfing, fencing, wrestling, taekwondo). On the opening day, the numbers had still been as low as 69 in Tokyo, 37 in Kanagawa, 31 in Saitama, and 30 in Chiba – making this a median increase of over 200 percent. Among the participants in the Olympics alone, the number of infected people had risen to 553 by the final day.

Nevertheless, Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide and Olympic Minister Marukawa Tamayo declared that "the increase has nothing to do with the Olympics." They agreed with International Olympic Committee (IOC) President Thomas Bach, who had promised before the Games that there would be "zero risk for the Japanese people." Bach was ridiculed for this, also because he initially spoke of "Chinese" instead of "Japanese people." Was he already thinking about the next IOC playground, the 2022 Olympics in Beijing? Was Tokyo 2020 just a stopover on the seemingly endless journey of the IOC troop, led by Bach, that rakes in billions in profits at the expense of the local hosts and population?

Criticism of ‘Olympic aristocracy’

Bach had already come under heavy criticism in the weeks before the opening because he wanted to hold on to the Olympics at all costs, despite an increasing number of people in Japan being opposed to holding the Games during the pandemic. In May 2021, an Asahi opinion poll revealed that 83 percent were against holding the Games amidst the ongoing pandemic [Fig. 2]. Only 14 percent supported the decision by the government and IOC to hold the Games this summer. In due course, (now former) Prime Minister Suga's popularity plummeted to a historic low of 33 percent shortly before the opening ceremony in July and fell to 29 percent after the Games in August. During the Paralympics in early September, Suga announced he would retire from his posts as leader of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and Prime Minister. This political damage occurred despite the success of the Japanese athletes and despite the fact that the local hosts had defied the IOC’s urging to allow spectators after all [Fig. 3]. Bach had invoked a supposedly special Japanese culture of resilience and perseverance in an attempt to persuade the Japanese side to allow spectators into the stadiums and other sports venues.

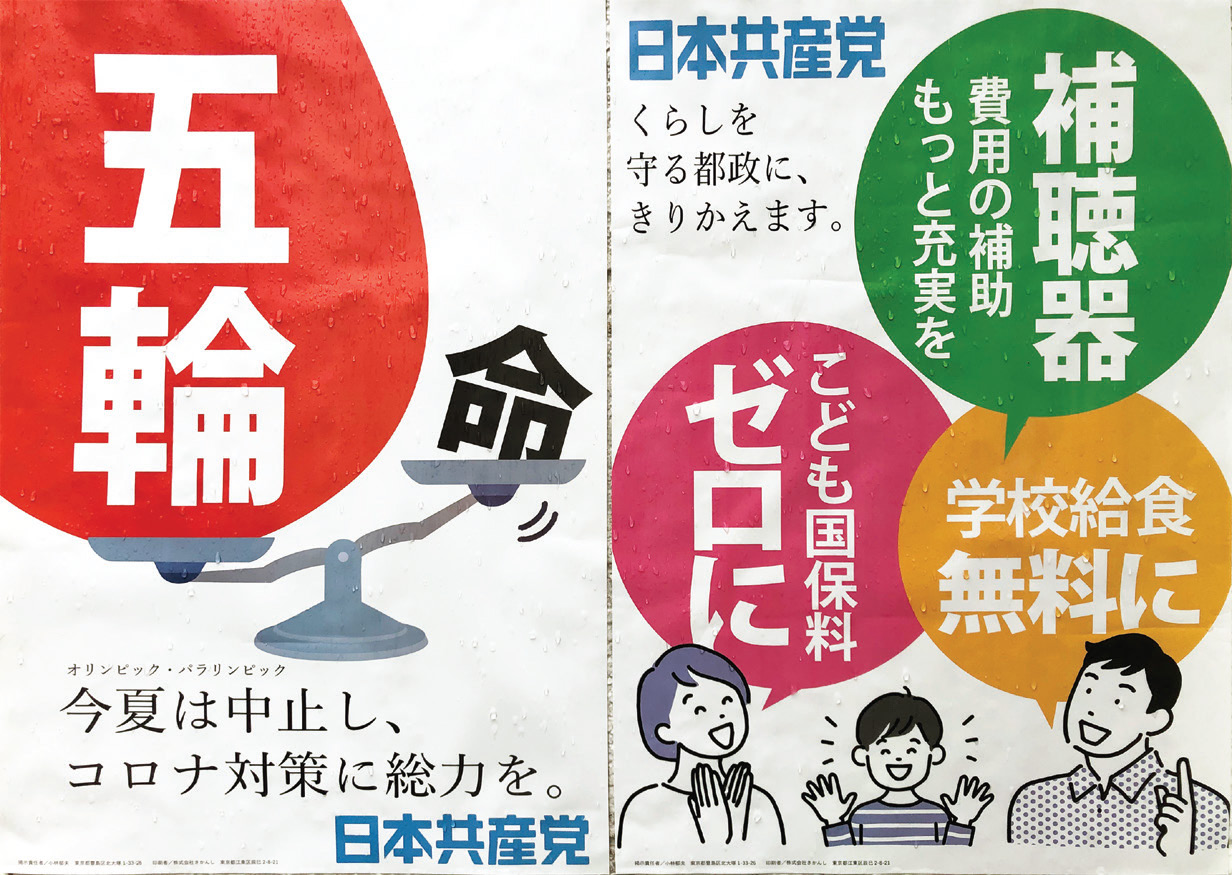

Fig. 2: Poster by Japanese Communist Party demanding the cancellation of the Olympics and Paralympics (Photo by the author).

Bach’s attitude earned him the nickname “Baron Von Ripper-off,” who, together with the IOC, “has a bad habit of ruining their hosts, like royals on tour who consume all the wheat sheaves in the province and leave stubble behind”. 3 The Japanese translation of “Baron Von Ripper-off” as bottakuri danshaku (ぼったくり男爵) went viral on social media. When Bach arrived in Japan in early July, protesters outside his luxury hotel demanded that he go home. Instead, Bach went to Hiroshima to spread his message of the Olympics as a celebration of peace. Bach did not heed the government's recommendation to refrain from non-essential travel, nor did he comply with the 14-day quarantine mandatory for others entering the country. On top of that, the IOC refused to cover the costs for the security measures in Hiroshima of about 3.8 million Yen (30,000 Euro), leaving the city of Hiroshima to pick up the tab.

Nevertheless, the critique of "Olympic aristocracy" and Olympic "celebration capitalism" 4 in Japan remained the weak movement it had been from the beginning. Already in 2013, an anti-Tokyo 2020 movement consisted of a handful of protesters. But against the background of the pandemic, opposition to the Games continued to rise and was joined by the national union of doctors, nurses, and newspapers, as well as celebrities such as Olympic swimmer Matsumoto Yayoi and Rakuten founder Mikitani Hiroshi, who called the plans to hold the Olympics amidst the pandemic a "suicide mission.” Within weeks, 352,000 people signed a petition to cancel the Olympics, organized by lawyer-activist Utsunomiya Kenji, who presented the petition to Tokyo’s governor Koike Yuriko in May. Nevertheless, anti-Olympics demonstrations rarely drew more than several dozen people [Fig. 4 and 5]. In Greater Tokyo, even the largest demonstrations saw less than 0.001 percent of the area’s more than 30 million people participate. As Sonja Ganseforth writes, the core of the demonstrators was primarily concerned with making a simple statement: showing “the difference between zero and one.” 5 Public protest against social or political grievances remains the preserve of a tiny minority in Japan, even if the Games have ensured that media coverage has made demonstrations more visible than before.

A push for human rights?

Indeed, some of the strongest criticism of Tokyo 2020 and the IOC came from outside of Japan. And as ever, the Japanese decision-makers grudgingly caved in to pressure from abroad (外圧gaiatsu): among others, the President of the Organizing Committee Mori Yoshiro, opening ceremony music composer Oyamada Keigo, and creative directors Sasaki Hiroshi and Kobayashi Kentaro resigned or were fired because of sexist comments, bullying of classmates with disabilities, and Holocaust mockery, respectively. In all cases, pressure came from international media and organizations, including the Simon Wiesenthal Center. Although the decision-makers reacted relatively quickly, the question remains as to why such discriminatory statements and views, some of which have been publically known for years, are apparently not an obstacle to occupying prominent positions in Japanese society. What mechanisms are at work that do not prevent this from happening in a pluralistic and democratic society like Japan? Or is it possible that the majority of Japanese society lacks awareness of human rights, diversity, and inclusion? Former Japanese diplomat Tanaka Hitoshi wrote after one of the scandals: "Japan is only now learning how important human rights are."

For decades, people have talked and written about Japan's "lost decades," referring to Japan's weak economic development – especially in comparison to South Korea and China – after the country’s economic bubble burst in 1989. Does Japanese society now also have to admit that it has lost decades in terms of equality, diversity, internationalization, and human rights? Who within Japan is able to explain current international debates and standards to the Japanese society? When will international experience abroad and multilingualism – prerequisites for knowing and understanding the world outside of Japan – stopped being seen as a flaw and a career brake, rather than as a plus? Appreciating international experience and intercultural competence should be a matter of course in a country that courts recognition from abroad like hardly any other highly developed industrial country – be it through Nobel Prizes or international mega-events such as the Olympics or World Expositions (which is scheduled to be held in Osaka in 2025, a record third time in Japan after World War II).

Fig. 3: Anti-Olympic protest in front of the Japan Olympic Museum (Photo courtesy of Barbara Holthus).

As Robin Kietlinski writes, “Japan has essentially been lobbying, bidding, preparing for, or hosting the Olympic Games almost constantly since the 1930s,” including bids for 1984 (Sapporo), 1988 (Nagoya), 1998 (Nagano), 2008 (Osaka), 2016 and 2020 (both Tokyo). 6 And despite Japan’s sour experience with Tokyo 2020, the next Japanese city is preparing its next Olympic bid: Sapporo, where this year’s Olympic marathon events took place, is set to apply to host the 2030 Winter Games. Should its bid be successful, the city in the far north of Japan would win the bid for the third time after 1940 and 1972. The 1940 Winter Games, of course, did not take place because of World War II, just like the 1940 Summer Games, which the IOC had awarded to Tokyo in 1936. Tokyo would have been the first city outside Europe and America to host the Games in 1940 [Fig. 6]. At that time, Japan was already deeply enmeshed in the war against China. It had occupied Manchuria in 1931, founded the puppet state of Manchukuo there in 1932, and left the League of Nations in 1933. While preparations for the 1940 Olympics were underway, Japanese soldiers massacred tens of thousands of civilians in the Chinese capital of Nanjing ("Nanking Massacre"). It was not until July 1938 that the IOC, the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC), Tokyo, and the Japanese government agreed to officially return the right to host the Games to the IOC. "Tokyo 1940" never took place and, therefore, went down in history as the Phantom Olympics. 7 Unlike the omnipresent references to 1964 in Japan’s public sphere in the run-up to Tokyo 2020, the history and legacy of the forfeited Games of 1940 was largely ignored or downplayed. 8

Japan’s Olympic traumata

While not hosting the 1940 Games was due to actions of aggression by Japan, the postponement of Tokyo 2020 was hardly Japan’s fault. Consequently, the old guard of Japanese politicians, symbolically led by the longest serving Deputy Prime Minister in Japanese history, Aso Taro (in office 2012-2021), prefers to blame higher powers for Japan's Olympic traumata. Aso spoke of "cursed Olympics every 40 years:” the Phantom Olympics in 1940, the Boycott Olympics in 1980, 9 and the Corona Olympics in 2020. Of course, the pandemic cannot be blamed on Japan, but the handling in Japan has been problematic from the start. Instead of taking the situation seriously, the problem was ignored until the 2020 Games were finally postponed in March 2020. The next day, the Japanese government suddenly admitted that there was a problem with the pandemic in Japan after all. When the infection figures briefly dropped in the summer of 2020, the Japanese government launched its "Go To Campaign,” with which travel across the country and restaurant visits were subsidized by up to 50 percent. In the short term, this benefited hotels and restaurants, as well as the population eager to travel. In the long term, it benefited the virus. To be sure, the lurching course of the Japanese government has not exactly helped to convince the population how best to deal with the pandemic. This also applies to the decision to hold the Games this summer. “The hosting of the Olympics and the world gathering in Tokyo has given the wrong signal to the population,” says Barbara Holthus, a sociologist at the German Institute for Japanese Studies in Tokyo and main editor of Japan Through the Lens of the Tokyo Olympics.

Legacies of Tokyo 2020: Gold, debts, infections

What will remain as the legacy of the Corona Olympics and how will the Games be remembered? The sporting successes are undisputed – and were to be expected for the Japanese team. In the new events of surfing, climbing, skateboarding, karate, baseball, and softball alone, Japanese athletes won 14 medals. In total, Japanese athletes won 58 medals, including 27 gold. Both are new Olympic records. A total of 20 new world records were set at Tokyo 2020 as well. But were the competitions fair, beyond the usual suspicions of doping? In an interview with the Japanese edition of Newsweek, JOC board member and Olympic medalist Yamaguchi Kaoru criticized the Games as “dangerous and unfair.” Because of the COVID-19 contact restrictions, foreign athletes lacked proper training opportunities upon arrival in Japan while “the Japanese athletes got to practice and prepare as normal before the big day.” 10 This “host nation advantage” was further strengthened by the fact that – given the strict rules regulating the athletes’ stay and movement – foreign athletes had less time to overcome jet lag and, above all, to get used to the inhospitable climate, which proved disadvantageous for long-distance travelers and those not used to a subtropical summer with 80% humidity. In the men's marathon, which had been specially moved to the supposedly milder climate of Sapporo, only a third of the runners finished the race due to the high physical stress caused by the humidity. This was also a new Olympic record.

More than the sports, evaluations of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic legacy will probably be dominated by the pandemic and the financial costs. Experts estimate that the postponement by one year and the loss of revenue (e.g., from ticket sales) cost at least 4 billion Yen (31 million Euros). The total cost of the Games is now estimated at up to 25 billion Euros, yet another Olympic record. 11 Who else will have to foot this bill but the Japanese taxpayer? Not included in these figures are costs for the prolonged and worsened situation due to the spread of COVID-19. By excluding the public and banning public viewing, the Olympics-induced rise in infections may have been kept in check to some extent. But many Japanese took advantage of the loopholes at the torch relays through Japan and at the outdoor running and cycling tracks, such as the Olympic walking and marathon events in Sapporo. There, people stood close together to cheer on the runners and walkers. The very decision to hold the Games and allow tens of thousands of athletes and officials into the country for the Games may have encouraged parts of the population in Japan to not take the COVID-19 restrictions too seriously. If the IOC and JOC have the confidence to hold “safe and secure” Games with tens of thousands of guests from abroad, then surely having dinner with a few friends or drinks with colleagues cannot be too dangerous?

The pitfalls of Japan’s safe and secure-ism

"Safe and secure" (anzen anshin 安全安心) has probably been the most used expression in the Japanese public in connection with the Tokyo Olympics in recent weeks and months. It is not surprising that a study by the Mitsubishi Research Institute (MRI) found that most Japanese named as their desired Olympic legacy "the safest society in the world, where both the population and visitors feel secure." 12 However, respondents did not state this goal after the outbreak of the pandemic, as one may expect. Instead, this was the top response in all six surveys conducted by the MRI from 2014 to 2019 – that is, prior to the pandemic. Anzen anshin is part of the consciousness of many Japanese that has contributed to making Tokyo one of the safest mega-metropolises in the world. At the same time, however, the triple disaster of earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown in March 2011 has revealed the emptiness of this slogan in the face of real crisis.

Fig. 4: Anti-Olympic protest near the Olympic Stadium on the evening of the closing ceremony (Photo courtesy of Felix Lill).

Comparing the triple disaster and the pandemic, Okada Norio, an expert in disaster prevention research at Kwansei Gakuin University, warns that the awareness and preparation for disasters in Japan is not sufficient. “The central government is too far away from many crisis frontlines, too bureaucratic, slow, and passive,” Okada says. “Another problem is that politicians and scientists are reluctant to communicate problems to ordinary people or to share important information with the public.” 13 At least regarding the ongoing pandemic, the reluctance of scientists to communicate the seriousness of the situation to the Japanese public seems to have been less of a problem than the willingness of the Japanese government and Olympic stakeholders to admit how dangerous the situation really is.

In the long run, comparisons with Japan’s handling of the triple disaster may not seem too far-fetched. Japan’s pandemic-related death toll surpassed 15,000 shortly before the opening of the Games in July and rose to 16,373 on the day of the closing ceremony of the Paralympics. It looks set to overtake the official death toll of the triple disaster of 2011 (19,747) before the end of 2021. The current number of COVID-19 related deaths in Japan is much lower than death rates per capita in countries like the United States, Russia, and Germany. But it is considerably higher compared to other countries in the region that implemented similarly rigorous immigration policies to control the pandemic, including South Korea (2,315), Australia (1,036), and New Zealand (27). 14 The initial branding of Tokyo 2020 as ‘Recovery Games’ to show the world that Japan had overcome the shock and damages of the triple disaster had been criticized even before the outbreak of the pandemic: instead of supporting the people and areas that had been affected most, the massive Olympic budget took away resources needed for rebuilding the destroyed areas, preparing for future disasters, and promoting sustainable alternatives to nuclear energy. In his bidding speech at the IOC meeting in Buenos Aires in 2013, then Prime Minister Abe Shinzo famously claimed that the situation in Fukushima “is under control” and that Tokyo was “one of the safest cities in the world, now... and in 2020.” 15 Eight years later: different Prime Minister, different crisis, similar rhetoric. Which lessons has Japan learnt from the triple disaster?

Lasting impact of diversity and inclusion?

In a country where being different is often associated with disruption and potential danger, an exaggerated sense of anzen anshin may also obstruct social inclusion and diversity. The opening and closing ceremonies, however, gave a stage to people with disabilities, multinational backgrounds, and different ages in an unprecedented way. In a display of gender-balance and racial awareness, basketball player Hachimura Rui, whose father is from Benin, carried the Japanese flag at the opening ceremony together with female wrestler Sasaki Yui. Moreover, the Olympic flame in the National Stadium was lit by no other than female tennis player Osaka Naomi, whose father is Haitian, and who is a prominent supporter of the Black Lives Matter movement. It is to be hoped for Japanese society that this spirit of diversity and inclusion was not extinguished together with the Olympic flame at the closing ceremony two weeks later.

Torsten Weber is a historian of modern East Asia and Principal Researcher at the German Institute for Japanese Studies (DIJ Tokyo), Japan. He has recently contributed two chapters on the Tokyo Olympics 1964 and the Phantom Olympics 1940 to the open-access publication Japan Through the Lens of the Tokyo Olympics (Routledge 2020). Email: weber@dijtokyo.org