Indigenous Community-based Water Governance in Assam, Karen, Papua, and Sabah

What is water? A scientist may say H2O. An economist a scarce natural resource, a nutritionist an essential nutrient. All are correct. All are also scientific and/or materialist understandings of water. Without consciously realizing it, these are the understandings that are often most familiar, especially for those of us who were raised in Western societies.

However, freshwater – much like other natural phenomena – also holds cultural and spiritual meaning. Laborde and Jackson capture this nicely with their distinction between modern water and Living Waters – the former refers to water as a substance to be utilized and managed, while the latter is an Aboriginal Australian concept that refers to water that is in relationship with people and other beings. 1 Living Waters' particular essence/meaning is derived from those relationships, and this is particularly true for people who grew up in Indigenous communities anywhere in the world.

This Focus section presents four articles on community-based water governance, all of which are (co-)written by Indigenous authors. They cover a vast area in Asia – Assam/Nagaland, Karen State, Sabah, and Papua. What shines through in each of these discussions is the reality of Living Waters as relational and shaped through the ontologies of each of these communities. An ontology concerns people’s “understanding of the nature of reality to determine what exists and how all that exists relates to each other.” 2 An individual’s or community’s ontology underpins knowledge and practices; it is shaped slowly over time in a society, often across multiple generations. 3 We are excited by how the Indigenous (co-) authorship of this issue conveys Indigenous community-based water governance from within the communities’ ontologies.

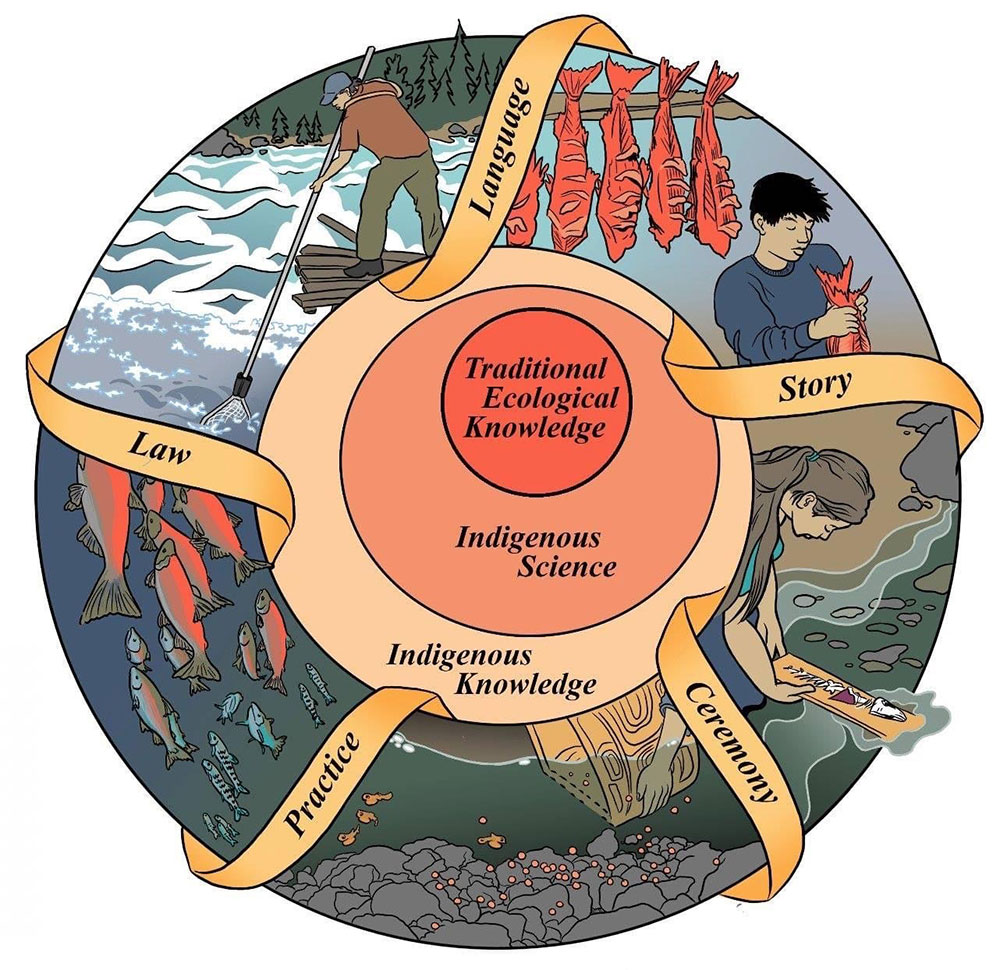

Fig. 1: Artist impression of the interconnectedness and reciprocity that characterizes Indigenous ontologies. (Artwork by Nicole Marie Burton Reid. Reprinted with permission. As featured in A.J., N.C. Ban. Accepted. “Indigenous Leadership is Essential to Conservation: Examples from Coastal British Columbia.” In Navigating Our Way to Solutions in Marine Conservation. L.B. Crowder, ed. Open Book Publishers.)

The articles underline the non-materialistic and non-scientific understandings of waterbodies that characterizes Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge about water in these communities. The collection further illustrates that, despite the many differences between Indigenous Peoples in Asia (and around the world for that matter), one of the common characteristics between Indigenous ontologies everywhere is the interconnectedness and reciprocity between Indigenous Peoples and their (often enspirited) ancestral lands. Moreover, the physical world is closely tied to ancestral land. Figure 1 – co-created with First Nations peoples from Canada – aims to visualize this, and it illustrates how Indigenous knowledge and practices are carried by languages and stories over time, through ceremonies and practices that are guided and protected by law.

Dr. Prithibi Pratibha Gogoi belongs to the Ahom Indigenous group and is related to the Dimasas through marriage. In her article, “The Entangled Sphere of the Dimasas’ Socio-Cultural Life and Its Implications for Water Governance,” Gogoi shows the important role of the river as an intermediary between life, death, and rebirth, and the analysis demonstrates how the river is one of three things a Dimasa cannot live without. She illustrates how Dimasa identity is intertwined with waterbodies by explaining their use of traditional Khernai water retention ponds, their interaction with the Dakinsa water spirit, and their ties to the Dhansiri and Brahmaputra rivers.

Andrew Paul, Saw Sha Bwe Moo, Robin Roth contribute a piece on water and fish conservation in the Salween Peace Park in Karen State, Myanmar (Burma). This territory was the birthplace of Saw Moo, a member of the Karen Indigenous group, who was born into a traditional Animist community. Their article, “Water and Fish Conservation by Karen Communities: An Indigenous Relational Approach,” makes clear how Karen societies developed around and through interaction with the river. From the examples of two Karen fish conservation areas, we learn that humans are perceived as custodians of the water, land, and forest – not the ultimate owners. Spirit beings play an active role in shaping water governance by Karen communities in traditional Kaw territories. In their discussion, the authors highlight the need to pay attention to Indigenous Peoples’ beliefs, values, and practices. What is called for is upholding humans’ relations with more-than-human beings, rather than a dominating focus on management of land, forests, water, and species that treats these as mere inanimate phenomena or irrational and irrelevant beings that are separate from how people relate to water.

Elisabeth Wambrauw belongs to the Biak tribe in Papua and draws on her own research and that of her students. Her article, “Water Governance from the Perspective of Indigenous Peoples in Papua,” provides an overview of water governance by Malind Anim, Enggros, and Sambom tribes. Her insights on traditional cultivation, irrigation and drainage systems, and zoning-based river governance feature characteristics similar to those described in the other articles. However, her description of the important role of totem and the metamorphism of spirits adds another layer of interconnectivity between humans and the world around them. This interconnectivity underlines the depth and complexity of Indigenous community-based water governance systems.

Adrian Lasimbang, a member of the Kadazan-dusun Indigenous community, discusses what drives the success of the micro-hydroelectricity mini-grids which he has been working on with Indigenous and rural communities in Sabah, Malaysia. In “Use & Protect: How Indigenous Community Watershed Management in Sabah Sustains Micro Hydro Systems,” Lasimbang explains how community-based watershed governance that aligns with traditional knowledge is key for realizing renewable energy solutions at the local level. Referring to traditional Tagal practices, he illustrates how this creates ownership at the grassroots level, which benefits conservation and also ensures that local communities are committed to maintaining the local micro-hydro systems.

These different understandings of water – i.e., ‘modern water’ versus ‘Living Waters’ – are increasingly recognized. For example, the Whanganui river in New Zealand was officially recognized in 2017 as “an indivisible and living whole” 4 with legal personhood in law – a reflection of her status as a living force in the ontology of local Māori tribes. But there is still a long way to go, which also motivated us to bring these four articles together for The Focus.

The importance of free-flowing rivers, a central feature in the Whanganui case, is something that can be seen as a common thread running through all four articles as an implicit warning about the threat that mega-hydropower dams pose to Indigenous community-based water governance systems. For the Dimasas in Assam/Nagaland, rivers should never fall silent since stagnant water leads to pollution, which directly threatens the Dakinsa river spirit who exclusively resides in clear water. In Sabah, a community-based micro-hydro project designed as a runoff river system does not require construction of large dams, standing in sharp contrast with the controversial Kaiduan dam. According to Indigenous communities, the Kaiduan dam (if built) would be deeply destructive to both the environment and their way of life. A free-flowing Salween is of crucial importance to Karen, as it supports their sacred relationship with the river and the beings living in its watershed. It also safeguards unique biodiversity and cultural practices which depend on the ebb-and-flow heartbeat of a free-flowing river. Wambrauw in Papua carefully describes how communities’ very identities diminish if the totem animal, plant, or phenomenon a community is linked to becomes locally extinct or disappears. This offers clear proof of how the wellbeing and fate of the local ecosystem is directly related to the wellbeing and fate of local Indigenous communities.

We leave you as Focus readers with a request not to romanticize Indigenous community-based water governance. This is not an exotic anthropological debate but rather a life-or-death issue for Indigenous Peoples. It is a matter of respect at its very core. It is critical to treat Indigenous ontologies as equal to the dominant ontologies currently informing mainstream economics, politics, and conservation practice today. It is a matter of equity and dignity.

Indigeneity is not about trying to preserve the past in a globalizing world. But because of Indigenous Peoples’ unique ontologies, they experience global issues in a particular way. Indigenous communities face particular challenges, and they are able to offer unique solutions and propose alternative development models that start from local Indigenous knowledge and practices.

We hope this free-to-access compilation of articles by different Indigenous (co-)authors in Asia increases your understanding as much as it did ours during the process of bringing these articles together. We wish that it supports emerging cross-border collaboration and knowledge exchange between Indigenous communities on the governance of Living Waters.

Saw John Bright is an Indigenous Karen and water governance program coordinator at the Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (https://kesan.asia), a community-based organization working to gain respect for Indigenous people’s knowledge and rights. KESAN works to achieve environmental sustainability, gender equality, and local participation and ownership in the development process in the Salween riverbasin in Myanmar/Burma. Email: hserdohtoo@gmail.com

Bram Steenhuisen is Frisian and a SOAS, Essex, and Wageningen University alumnus. Bram works on multi-stakeholder dialogue, beliefs-and-values based nature conservation, and community-based water governance in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Email: bramsteenhuisen@gmail.com