Do You Speak North Korean or South Korean? The Korean Peninsula’s North-South Split Has Created a Distinct Linguistic Divide

In the closing days of WWII, the Korean Peninsula, home to one of the most ethnically homogenous populations in the world with political boundaries among the oldest on earth, was arbitrarily divided by the great powers. Competing regimes have since applied contrasting approaches of policy and planning to the Korean language, which have far-reaching implications for possible reunification and for North Korean refugees living in the South.

What’s happened to language since the Peninsula was divided

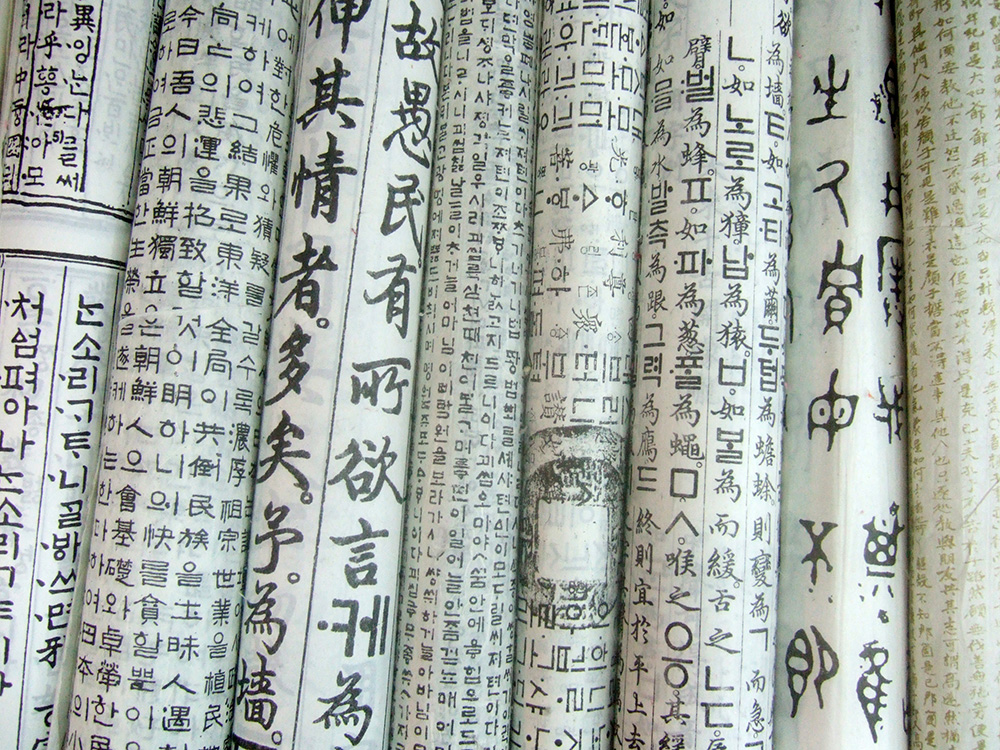

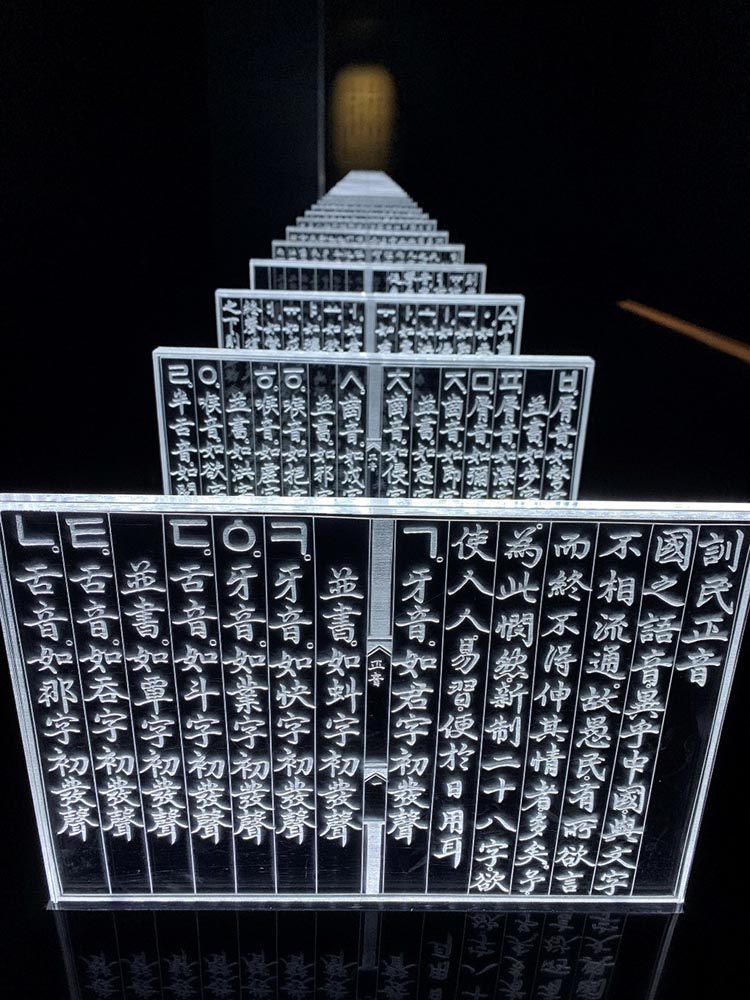

In South Korea post-1945 there was an impetus to remove hancha 1 (Chinese characters) in favour of hangul only, and to expel Japanese loan words from the language. But more recently, the country’s overall laissez-faire approach to its language has meant that language change has been largely driven by the linguistic market and the whims of the public. This has meant the increasing influence of English on the Korean language.

In the North, hancha was also removed in favour of hangul-only writing, as the North placed a premium on mass literacy for the effective spread of propaganda and the advancement of socialist revolution. According to Soviet sources, 2 beginning with a 1945 illiteracy rate of more than three quarters (and even higher for mixed script), 3 North Korea virtually eliminated illiteracy even before the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950.

However, it is North Korea’s language policies from the 1960s that laid the foundations for more drastic divergence between the language varieties and has posed the greatest challenges for saet’ŏmin (North Korean refugees).

In that decade, the North Korean leader Kim Il-sung conducted and published his so-called ‘Conversations with Linguists’ (1964 and 1966), in which he portrayed the southern variety of Korean as “inundated with foreign borrowings,” a “gibberish mixture of Chinese, Japanese and English” that had lost its ethno-national characteristics, necessitating the state’s intercession to defend the language. 4 In addition to the explicit proscription of foreign borrowings (especially from English and Japanese), Kim called for creating pure (North) Korean words to replace not only Japanese and English loan words, but also the extremely numerous Sino-Korean vocables as well.

A successful campaign to do away with (obvious) Japanese loans also unfolded in South Korea, and so the first area was not as consequential. But in the case of English loans and Sino-Korean vocabulary, these proclamations by Kim and the subsequent policies they engendered have resulted in a profound divergence of the Korean varieties.

Research has shown that the greatest divergence between the languages has been in the various areas of lexicon. These include synonyms like kungmin (국민 citizen; NK: 인민 inmin), words with the same spelling and pronunciation but different connotations such as tongji (동지 friend or colleague; NK: comrade), remaining Sino-Korean words such as minganin (민간인 civilian; NK: samin 사민 private citizen), and even the pronunciation and spelling of limited loan words such as k’ŏp (컵, NK: koppu 고뿌 cup), the latter revealing Russian influence. 5

The most highly publicised (and for some snicker-inducing) changes, however, are the North Korean attempts at actively creating pure Korean words in place of Sino-Korean words. Examples include terms such as Hanbok (한복 traditional Korean clothing; NK: Chosŏn ot 조선옷 [North] Korean clothing), hongsu (홍수 flood; NK: k’ŭn mul 큰 물, “big water”), sirŏp (시럽 syrup; NK: tanmul 단물, “sweet water”), rek’odŭ (레코드 [music] record; NK: sorip’an 소리판, “sound disk”), and p’ama (파마 perm; NK: pokkŭm mŏri 볶음 머리, “fried hair”).

An uphill battle for North Korean refugees adapting to South Korean linguistic life

The significant number of successful adaptations along with the effective limitation of foreign borrowings has contributed to the creation of a very distinct language variety. This directly affects the linguistic assimilation of North Korean saet’ŏmin when they settle in the south. It is estimated there are 34,000 North Korean refugees living in South Korea. 6

According to one study, while South Koreans tend to underestimate the differences between the language varieties and the challenges they pose to new settlers, saet’ŏmin ranked linguistic challenges as the most significant impediment, with over 70 percent of respondents reporting ‘much difficulty’ or ‘considerable difficulty’ due to language. 7 . Hyŏndae Puk Han Yŏn’gu 8, no. 2 (2005): 85-124; 101, 108.] Importantly, all of the 34 saet’ŏmin interviewed as part of this study indicated language difference as a contributing factor to difficulty in work life.

Significant percentages of respondents reported experiencing difficulties due to differences in pronunciation and intonation, the extensive use of English expressions in South Korea, differences in honorifics, ignorance of hancha, not knowing the name for an object or everyday vocabulary word, and a feeling of self-consciousness when interacting with southerners. 8

Research has also reported extensive discrimination experienced by saet’ŏmin due to language difficulties. 9 Instead of revealing their true identities, many respondents are either mistakenly ascribed or assume the identity of ethnic Korean Chinese (Chosŏnjok), various Korean dialect speakers, or overseas Koreans. This suggests that many saet’ŏmin view their background and identity as an impediment or mark of shame rather than a potential asset that might be fostered.

As the population of saet’ŏmin inevitably increases in the south, the difference between the North and South Korean language varieties will continue to be a salient issue. Reflecting the perceived widening gap between the languages, work began in 2005 on the Kyŏremal k’ŭn sajŏn (Unabridged Dictionary of Our Language), 10 an ongoing joint project involving experts from North and South Korea that seeks to index the entire Korean language and ‘re-converge’ the varieties. Moreover, in the event of political unification, the issue would have even more intense and far-reaching ramifications for the entire population of the Korean Peninsula, as it grapples with social inequality, discrimination, and power imbalances.

Fig. 6: Image from the National Hangul Museum, Seoul, South Korea. (Photo courtesy of Daniel Pieper, 2023)

Not only is it paramount that we identify the different areas and specific reasons for linguistic difference, but also that we determine how this history of linguistic change continues to affect the two Koreas today. Moreover, extra care must be taken not to demonise either variety, blame either side for the linguistic divergence, or identify either language as flawed or an impediment that needs to be eliminated or overcome. Rather, it is crucial to embrace linguistic diversity and acknowledge pluricentric Korean as an unexpected, though at this point established, byproduct of political division.

Daniel Pieper is a Korea Foundation Lecturer in Korean Studies at Monash University. Email: Daniel.Pieper@monash.edu

This article is a shortened version of an article originally published by Melbourne Asia Review, Asia Institute, University of Melbourne.