Dead Wet Girls versus Monstrous Mothers: The Female “Monster” in Japanese Horror Cinema

The supernatural, especially ghosts or spirits, have captivated the imagination in Japan for centuries, as evident in the prevalence of the supernatural as a subject in Japanese art, literature, theatre, and cinema. Although not explicitly referred to by the name, supernatural “horror” films have been produced for almost as long as the history of cinema itself in Japan. 1 The prevalence, or one might even say popularity, of the supernatural female specifically is apparent in Japan from as early as the eighth century and carried on through to present day. Over time this tendency to portray the feminine as “monstrous” has continued, even increased in prominence, to the extent that Japanese horror films today are rarely without a haunting female “monster” spirit as the primary antagonist.

As in many other cultures, the feminine is often portrayed as having an affinity with the supernatural, even the monstrous or evil, by the sheer fact of being female. In Western horror cinema, Barbara Creed refers to what she calls the “monstrous feminine,” wherein women are commonly represented as weak in horror films, except when represented as the villain, in which case they are inherently evil. According to Creed, however, this portrayal should be viewed more as by design than as something “natural”: “Woman is not, by her very nature, an abject being. Her representation in popular discourses as monstrous is a function of the ideological project of the horror film – a project designed to perpetuate the belief that woman’s monstrous nature is inextricably found up with her difference as man’s sexual other.” 2

By portraying the feminine as “monstrous,” an innate connection is drawn between woman and monster, highlighting their similar status as what Creed describes as both “biological freaks” within patriarchal structures, and consequently “potent threats to vulnerable male power.” Although Creed was largely referring to Western horror when she wrote, the Japanese horror film is no exception, with the female “monster” often seen to reflect patriarchal fears.

It should be noted, however, that in the 1990s there was a visible change in Japanese horror cinema, often attributed to the economic turmoil of the recession for Japan. With the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy in 1991, the country entered a period “marked by a sense of millennial crisis, social malaise, and economic stagnation,” a time referred to as the “Lost Decades.” 3 Initially produced utilizing the low-budget strategies of independent filmmakers, these films emphasized more of an atmospheric horror.

Although this was originally due to financial constraints, films produced with this effect sparked a renewed interest in what would later be referred to as the “J-horror” film, a new aesthetic that would become representative of the entire cinematic genre to overseas audiences. In the face of a crumbling economy and society in crisis, both audiences and filmmakers became almost entirely fixated on the “monstrous” female ghost. The female “monsters” that manifested as a result of these changes, however, were considerably different from those that appeared in supernatural films prior, and certain character tropes emerged.

The dead wet girl: Sadako of Ringu (“The Ring”)

Of particular note in this regard is the “dead wet girl,” a term first coined by film scholar David Kalat to describe the, at the time, very unique female ghost character emerging in J-horror. 4 Seen to be highly distinct from not only earlier Japanese supernatural films but also American horror, these characters are, as the term implies, dead and wet, but also specifically “girls.” While often literally “wet” with water, which is traditionally a common motif to evoke the supernatural, this wetness can also be seen as tied to the feminine, as in for example the cosmological concept of yin and yang, where the feminine is not only associated with the “dark” but also the wet. The dead wet girl can therefore be interpreted as a figure of untapped feminine power, which can in turn explain why she is typically portrayed as possessing extraordinary bordering on inhuman power. It is arguably out of fear of this potential power that the dead wet girl is persecuted. As a girl – in other words, a young, unmarried woman – she is full of vitality, regularly made “wet” through menstruation and thus ripe for pregnancy, but as yet unfettered by social obligations, namely marriage and motherhood. So long as she remains unfettered, the dead wet girl cannot be controlled and is a threat to society.

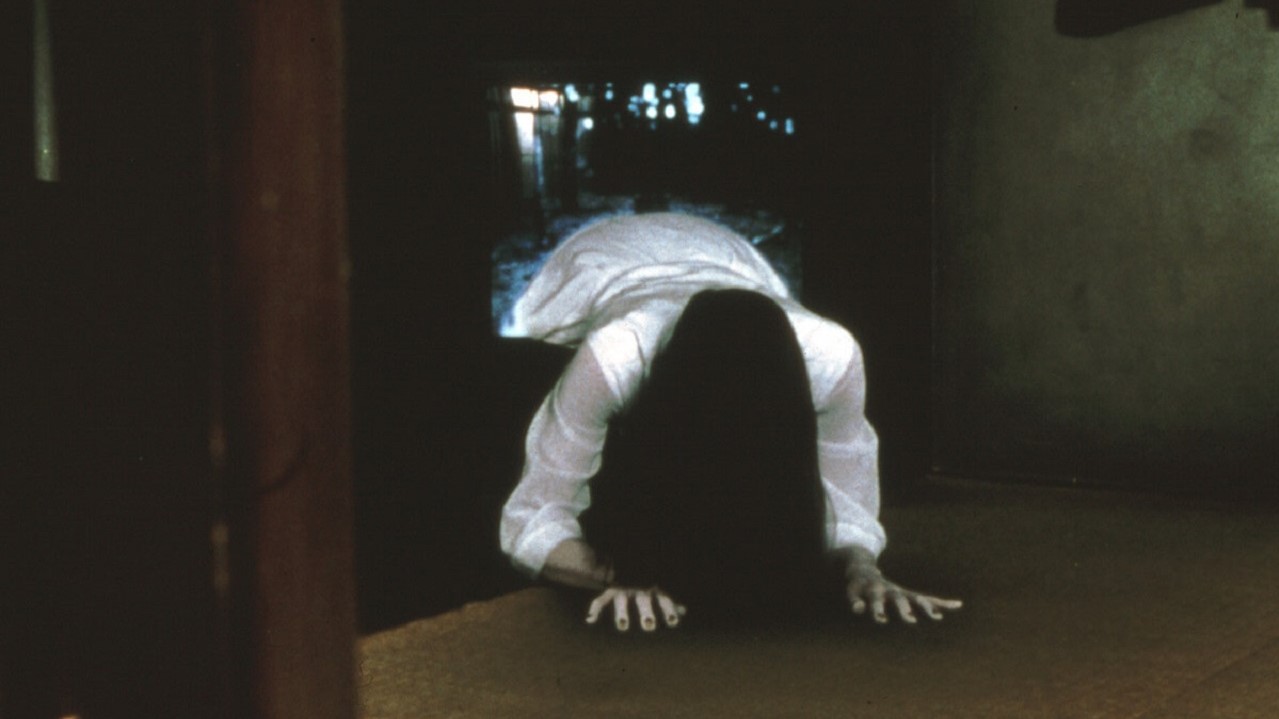

Fig. 2: Screenshot of Sadako emerging from a television to complete her killing curse in the film Ringu. Directed by Nakata Hideo, Toho, 1998.

The success of director Nakata Hideo’s first Ringu (リング, “The Ring”) film in 1998 is often credited with popularizing the genre internationally, and the character Yamamura Sadako is attributed as the official progenitor of the dead wet girl, making her perhaps the best-known figure of J-horror both within Japan and overseas. 5 Even those who have never seen a Ringu film recognize her image, often conflating her appearance with the entire J-horror genre. It is perhaps little surprise then that Sadako continues to serve as one of the strongest examples of the character trope.

While most may recognize Sadako as the “monstrous” female ghost who resides in a well and kills people using a cursed video that brings death to all who watch it, it is important to note that the character possessed extraordinary power while still alive as a little girl. In the first film, newspaper journalist Asakawa Reiko enlists the help of her ex-husband, Takayama Ryūji, who is both a professor and a psychic, to try and put a stop to Sadako’s curse before her time runs out in seven days. Their pursuits are made even more desperate when their son, Yōichi, also ends up watching the video. Over the course of their investigation, the two discover that Sadako’s mother, who was also gifted with preternatural power, was convinced to demonstrate her abilities in an attempt to prove the existence of extrasensory perception. During the demonstration, one of the attending reporters denounced her mother as a fraud, inciting his colleagues to join in on the ridicule, and was subsequently killed psychokinetically by Sadako. Ultimately, it is the fear of her potential power as Sadako fully matures that results in her being attacked and then thrown down a well to die, serving as the impetus for the entire franchise.

The nature of Sadako’s death being so inextricably linked to water further affirms her status as a dead wet girl. While water is often seen as a source for purification in Japanese religious belief, water has been continuously utilized as a visual motif to evoke the supernatural. This is largely due to flowing bodies of water, such as the ocean or rivers, being viewed as fluid boundaries between worlds of the living and the dead. In Sadako’s case, however, her death takes place in a “still” body of water, which cannot freely carry her spirit to the netherworld, her body left to rot inside the well. Combined with being cut off from flowing waters and thus incapable of moving on even if she wanted to, Sadako has been left to fester, both in body and spirit, in the well’s waters for years.

By the time Reiko and Ryūji find the well to try and recover her corpse, she is long since beyond any form of spiritual pacification, which may explain her indiscriminate desire to inflict suffering in the form of a video tape that anyone could potentially watch. It also explains why Sadako is not seen to be at peace at the end of Ringu and proceeds to kill Ryūji by emerging from his television that starts inexplicably playing her cursed video. It is revealed afterwards that what spared Reiko was not the recovery of Sadako’s corpse after all, but the fact that Reiko had Ryūji watch the video and made a copy of the tape, effectively aiding the female “monster” in the dissemination of her curse.

The monstrous mother: Kayako of Ju-On (“The Grudge”)

While J-horror cinema might seem to be largely dominated by the dead wet girl, a second major character trope that is equally present is the “monstrous mother.” Although her origins are closely tied to traditional, premodern views in Japan, the monstrous mother as she is seen in J-horror arguably reflects more the growing concerns over the fracturing of the nuclear household and its potential impact on Japanese contemporary society. According to Chika Kinoshita, “a casual survey of J-horror films is enough to fathom the depth of crisis in the normative family life of the recessionary Japan; single parents, abused, abandoned, and/or murdered children constitute most J-horror narratives.” 6

Fig. 3: Screenshot of Kayako’s hair in the film Ju-On: The Grudge 2. Directed by Shimizu Takashi, Lions Gate, 2003.

Concerns over this “crisis,” however, are largely focused on women and their specific role in the household that they are failing to uphold or are neglecting altogether. While women may not necessarily be expected to uphold traditional familial values structured around a patriarchal society as in premodern times, getting married and having children are still considered the most defining traits of womanhood in Japan. Even today, women wishing to remain independent and pursue careers past the age of 30 continue to face considerable prejudice and discrimination, especially single working mothers. The monstrous mother can thus be viewed as an expression of largely male or patriarchal anxieties about women becoming increasingly independent and breaking away from the established family norm. Consequently, the monstrous mother tends to be portrayed as a character who is not only seen to be similarly “non-traditional,” but also as a woman who has somehow “failed” her children, often by killing or abusing them physically or mentally, through neglect or violence.

Aside from Sadako, Saeki Kayako of director Shimizu Takashi’s Ju-On (呪怨, “The Grudge”) franchise is another iconic figure of J-horror. 7 While her appearance almost always comes paired with that of her son, Toshio, most viewers may find it difficult to recognize her character as a monstrous mother. Most will associate her more with having suffered great violence by her husband, Takeo, transforming her into the primary agent of the “Ju-On,” the curse or “grudge” that subsequently infects her house. As a result of the incident, she now targets anyone who enters the space.

The apparent impetus for the violence done unto her, however, has largely to do with Kayako’s status as a mother. In the 2002 theatrical film, Ju-On: The Grudge, it is hinted that Takeo killed both her and Toshio due to his suspecting that Kayako was having an affair and that Toshio was not in fact his biological son. In the direct-to-video version made of Ju-On two years prior, these suspicions are at least partially substantiated by Kayako’s journal, which reveals that she had been thoroughly obsessed with another man, though this could have been purely a one-sided infatuation on Kayako’s part. In both versions, the source of Takeo’s rage is less about his wife’s suspected adultery and more about his lack of biological progeny.

Overall, the audience is given little context for Kayako’s “monstrous” acts as a vengeful ghost. This is largely due to the fact that she is characterized as being physically unable to even walk, let alone speak for herself. Most will recognize the sound of the her eerie death rattle, a product of her husband’s violence, who brutalized her body and broke her neck in his fit of rage. How she physically presents to the audience altogether embodies her perceived “failures” as a mother.

The “woman” erased, the “monster” remains: J-horror today & beyond

Although it should be acknowledged that there is less of an imbalance in gendered representation of the “monster” in Japanese horror as of late, more J-horror films are still made featuring a female “monster” as the sole or primary supernatural antagonist rather than a male one. Despite the Japanese film industry having a history of making concerted efforts to attract young male audiences by utilizing action genres, such as the yakuza film in the 1970s and 1980s, thereby increasing the presence of both aggressive male characters and graphic violence in Japanese cinema, it is particularly notable that portrayals of male “monsters” have not significantly increased in J-horror films.

This implies an overall emphasis on conflating the feminine with the monstrous, with women being perceived as more fear-inducing in J-horror. Adding to this is the overall effect of commercialism on portrayals of the female “monster” in J-horror. More often than not, films are being made that notably reduce or heavily abstract her depiction as an actual woman character, and now seem to follow more of a checklist formula, diminishing her to an object, a prop piece in the scenery of Japanese horror. No longer does she really require a narrative to explain or justify her actions. Her image becomes virtually interchangeable with those found in other J-horror films.

A notable example of this can be found in the film Sadako vs. Kayako (貞子VS伽椰子), 8 which was a crossover film of the Ringu and Ju-On series. In the film, both Sadako and Kayako are depicted killing their victims utilizing their respective cursing methods, with no apparent hope of defeating either of them. The sense of futility is perhaps heightened by the fact that the speed at which each “monster” metes out her punishment has been rapidly accelerated, giving little time for victims to find a way to save themselves. 9 The solution that is proposed to save the two main female characters – Suzuka, who entered the Saeki house, and Yuri, who watched the cursed videotape – is to have Suzuka watch the video from inside the house alongside Yuri. Being thus afflicted by both curses, Sadako and Kayako would presumably battle one another over the two girls and destroy each other in the process.

Fig. 4: Screenshot of Sadako’s hair in the film Sadako vs. Kayako. Directed by Shiraishi Kōji, Kadokawa, 2016.

While this pitting of horror icons from popular franchises against one another is not an original concept, 10 what is notable is how the two female “monsters” are, barring some superficial elements, virtually indistinguishable from one another in the film. This is heavily affected by the minimal narrative details given on either character, resulting on entirely visual or aural cues to signify the two women. Even these identifiers, however, are seen to be used for the two interchangeably.

One notable example is when Yuri, who is only cursed by Sadako at the time, is taking a shower in the bathroom where she is visited by the female ghost in the form of masses of Sadako’s hair covering the ceiling and dropping down on her from above. This scene, however, is highly evocative of scenes from the Ju-On films. One of the most memorable scenes, aside from the climax, in Ju-On: The Grudge is of Rika in the shower feeling Kayako’s hand on her head while she is washing her hair. In Ju-On: The Grudge 2, the scene with perhaps the strongest visual impact is when Kayako kills characters Tomoka and Noritaka, the entire ceiling covered with her hair. In contrast, no such scenes take place in either of Nakata Hideo’s Ringu films.

Furthermore, Sadako’s well, which is arguably one of the most crucial visual features to her character, is almost completely altered in Sadako vs. Kayako. The well itself does not figure into the cursed video footage, nor is she seen crawling out of the well in the film, which is perhaps the most iconic scene of the Ringu franchise. In fact, the well that is present in Sadako vs. Kayako is not even hers, but one located on the grounds of the Saeki house. Ultimately, the well is only utilized at the end of the film when the plan to have the two female ghosts fight one another backfires horribly and Yuri sacrifices herself to lure them into the well so it can be sealed with all three of them inside. Instead, the spirits end up colliding and then combining to form a new entity that possesses Yuri’s body referred to as “Sadakaya.” The reveal of Sadakaya at the conclusion of the film serves as the epitome of this tropification of the female “monster” in Japanese horror. Who each woman was is both irrelevant and insignificant.

Fig. 5: Screenshot of Sadakaya emerging from the well in the film Sadako vs. Kayako. Directed by Shiraishi Kōji, Kadokawa, 2016.

Considering the effect and influence of the monstrous feminine begs the question of what the female “monster” truly represents for her audiences, both then and now, male and female. Is she merely a reflection of views and attitudes towards women through the eyes of male writers? Or perhaps she embodies the fears of men regarding women altogether? This is especially relevant for the J-horror film industry itself, as filmmakers are predominantly men, and it continues to be difficult for women directors to gain entry. For any aspiring director of J-horror to gain an opportunity, regardless of gender, they must first be mentored by established (male) directors, effectively making men the gatekeepers for the entire genre. The fact that there is really only one notable woman director actively creating J-horror films today, Asato Mari, 11 mentored by Kurosawa Kiyoshi, 12 is indicative of this.

As films have increasingly de-emphasized the personal narrative and humanity of the female “monster,” her status as a woman is steadily erased, making it virtually impossible for the audience to sympathize with her. This growing trend in portrayal runs the risk of being harmful to the self-perception of women. Not only can it potentially influence female audiences, but also future creators of horror. This is evident given that the term J-horror has come to be associated with an overall horror film aesthetic that almost requires the presence of a monstrous female. As other countries, both in other parts of Asia and in the West, have taken to adapting this aesthetic for their own respective horror cinemas, the far-reaching impact of Japanese horror cinema’s female “monster” cannot be disregarded.

Jennifer M. Yoo, Ph.D. is currently affiliated with Tufts University as a Lecturer in Japanese culture, film, and literature for the Department of International Literary and Cultural Studies.