Contemporary Chinese Master of the Traditional Papercut

Paper cutting is an ancient art in China largely performed by women in the countryside. Using red paper, they cut festive and auspicious images which are hung on doorways, windows, and elsewhere. For centuries the images and techniques survived in rural China. Recently such papercuts have become the focus of collectors, national programs, and professors who are dedicated to preserving the native art. Modern artists have taken this ancient art and transformed it into a new and exciting form of contemporary expression.

Largely an ancient women’s art transmitted from generation to generation in the countryside, Chinese papercut artists celebrate the national holidays of the Spring Festival and New Year with their designs. Nearly all homes- farmhouses to urban apartments- display the lively red designs on their door frames. Such works carry symbolic associations because they were traditionally used for religious rituals and to depict deities. Often made with red paper, the most propitious color, papercuts use auspicious imagery and often include such lucky characters as ‘Fu (福, blessing)’ ‘Xi (囍, double happiness)’ ‘Shou (壽, longevity) as well as more secular imagery. A fifth-generation papercutter in Yu County, Hebei Province, Zhang Haiquan explained the wide range of motifs used: opera characters, historical tales, flora and fauna, landscape scenery, lucky emblems, and activities from daily life grace windowpanes across China during the Spring Festival. 1 However, the art is in danger of disappearing as the rural population moves to the cities. Artist and historian Professor Lu Shengzhong has brought the appreciation of the art to a new height and created papercuts that relate to more contemporary art in their format, imagery, and techniques. Moreover, he trained several important artists at the Central Academy of Art in Beijing. In addition, recent governmental programs have given support to preserve the skill in the rural districts and to, in turn, stimulate the local economy.

Contemporary Chinese papercut artist: Lu Shengzhong

Lu Shengzhong was a most gifted artist and teacher who is celebrated for discovering the artistic potential of the traditional papercut and for making extrordinary works of art. 2 Lu (1952-2022) was born in Dayuji Village, in Shandong Province and discovered papercutting by watching his mother as a child. During his college years in the 1980s, Lu rejected the western-looking styles adopted in the academies of art, turning instead to the rural art of the papercut. As one of the important scholars and practitioners in the field 3 Lu employed and reused a small red figure derived from folk art [Fig. 1]. This figure is described as a paper figure for calling souls, having a baby, a wedding or funeral, and celebrating festivals. 4 As Lu said, “I use paper to cut this little red figure to demonstrate the delicate fragility of human beings. Ephemeral. A human’s life is shorter than a paper’s thickness. The material is not important. What is more important is the process you use to create that material. This is more valuable to me.” 5 Lu Shengzhong visited rustic villages to further study the art, relating his experience in his book, Calling Soul: “But when I arrived there, there wasn't a life-like flower at all, because they didn't create art according to real-life objects. Far from being naive, these were more mature than mainstream art, because behind them were thousands of year's historical accumulation. . . . Also, the old women were not illiterate. Apart from traditional customs, the patterns in their work were diverse and hard for us to learn; flowers, butterflies and phoenixes had different interpretations, . . . A piece of papercut for window decoration is a symbol for a dissertation. Together, all of them can make up a heavy book. When night falls, every household had distinct red papercuts on windows, which told different stories and conveyed varied concepts. All the villagers, young or old, knew the meanings, but we just saw the patterns — actually, we were 'illiterate.’ As I cut paper with my scissors and separate the shapes that result from my activity, I am making a statement against the separation of body and soul in contemporary thought. Summoning the detached forms of the souls so that they can be reunited with their bodies, the process echoes the juxtaposition of positive and negative forms or the perfect coexistence of the curves of Yin and Yang." 6

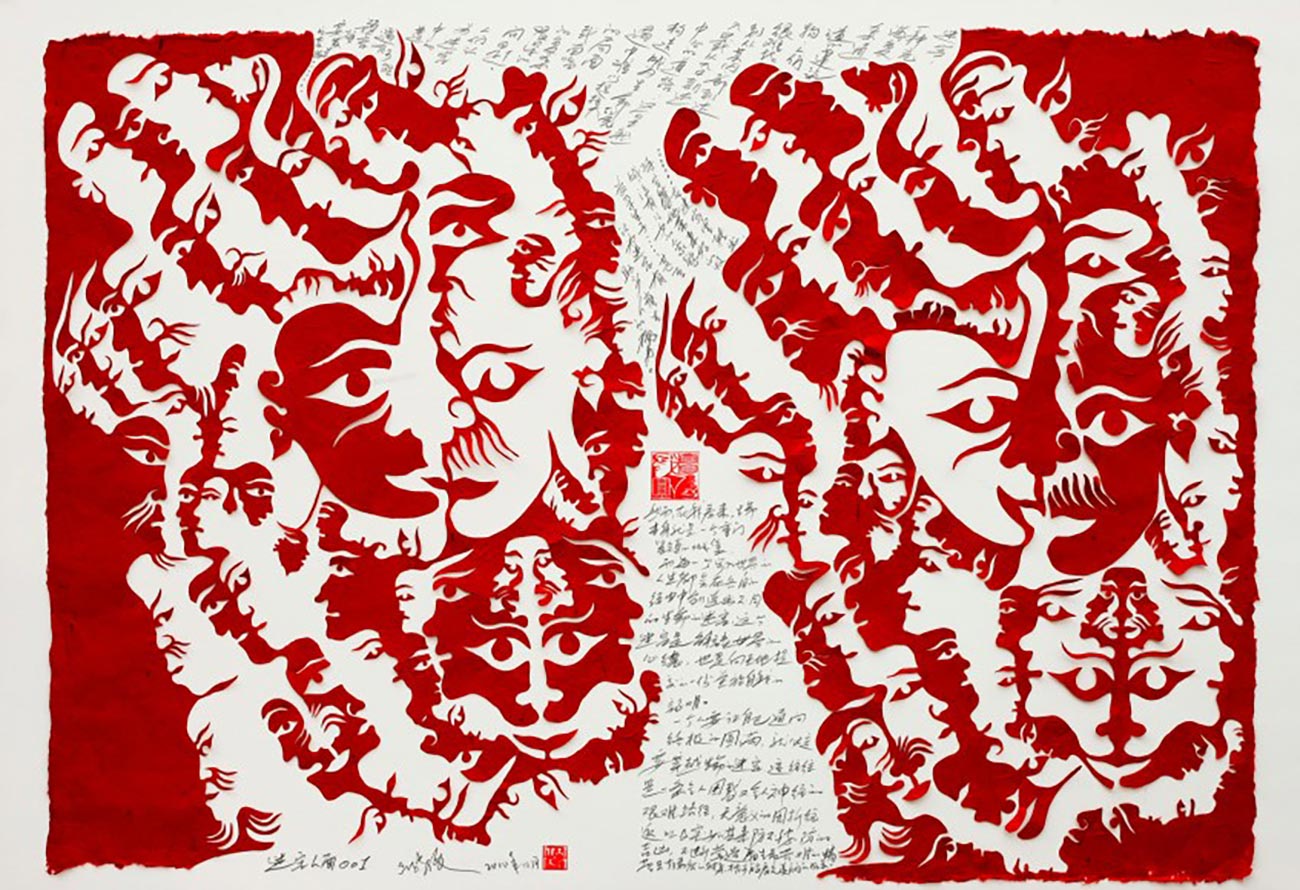

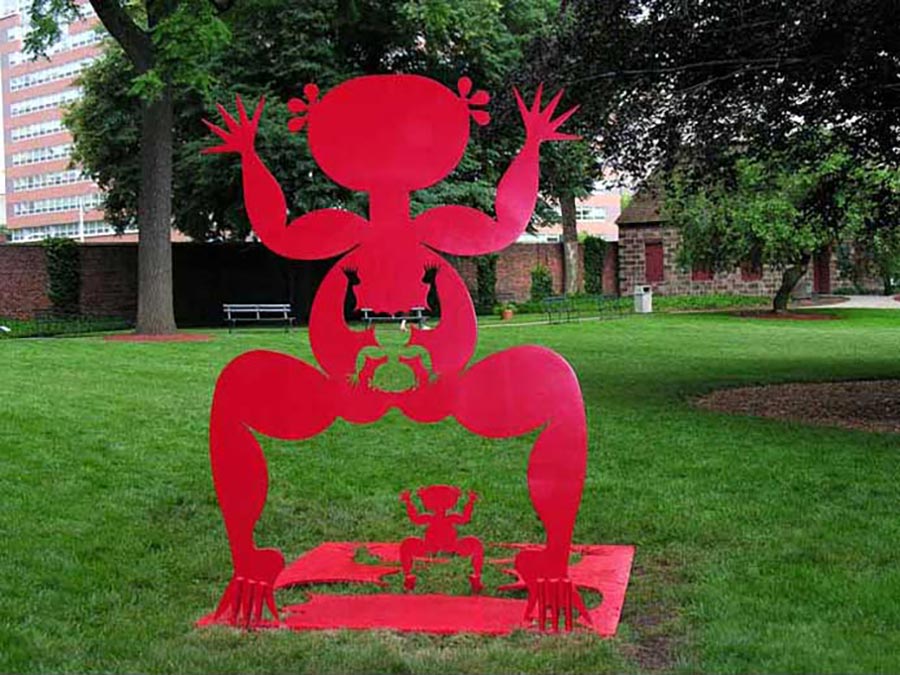

The red character is a flat two-dimensional representation of a child-like body: soft flesh lacking muscular development arranged in a symmetrical presentation with arms held up, palms up facing out, and extended fingers. Bent at the knee and outspread, the legs flank the body, and the feet appear claw-like. Two sprays of hair emerge on either side of the head, like the hair knots worn by prepubescent children. Its body is naked, as the curious articulation of the buttocks makes clear and reads as female, though gender specificity is lacking. Over the years, Lu used the image as a totem in dozens of configurations, with variations in size, placement, media, and formats. Among these formats he employed the paper bound book. For example, two pages from the 2004 Book of Humanity are identical: at the center of each page is a large red papercut on a white ground, two square frames repeat smaller images with ten little red people across and ten down [Fig. 1]. Soon, Lu considered not only the paper cut but the paper from which it was cut as important as the subject. Both were bearers of the image, positive and negative. Appreciation of the positive and negative space was an essential aesthetic concern in paper cutting, but for the first time, the scraps were not discarded and had equal value. Lu attests that “on these waste scraps of paper were visible the same spirit and emotion as in the ‘formal design’ I had cut out.” 7

Lu used his red person as a kind of script, like a Chinese character, he worked to employ the image in several dispositions with the potential to replicate it a great many times and in a variety of positions and sizes. His Book of Humanity was an enormously difficult project: cuttings and scraps filled 20 red volumes and 40 black volumes, each comprising 90 pages. By 2003, when the project was finally realized, he had employed seven expert papercutters and many others to prepare the pages and bind the volumes, beginning a method of using many helpers. 8 Lu’s work is archly ironic as he adopts a familiar folk art, an ephemeral living art practiced in the countryside which is a typically illiterate environment, and mounts it as a book, an icon of the thousand-year-old elite literary tradition. What is more, in the book format, his red figures act like characters in China’s ancient pictographic script. In consonance with several contemporary artists like Xu Bing (b. 1955 Chongqing) 9 and Wenda Gu (b. 1955 Shanghai), 10 Lu’s artistic efforts looked like writing while they did not communicate a legible message. While the former artists’ efforts were concerned with marks that mimicked calligraphy, Lu’s use of the image took on complex and multivalent meanings as representations of “humanity” or “souls;” and with the presentation of the positive and negative parts of the papercut, it evoked the philosophic duality of Yin and Yang, transient and long lasting, body and soul, and more. The configurations of the red figures did not convey a readable text, yet they perpetuated and preserved a primeval and idiomatic form of communication. Lu relies on the image to convey his message, much like the woodcuts. He also published two books illustrating his works and explaining his thinking. Working with a team of students and papercutters, Lu embarked on a monumental cut paper installation. Craftsmen and students used needles to cut and assemble a total of 600,000 paper men for the Human Brick exhibited in his solo show at Beijing’s Today Museum in 2015 [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2: Lu Shengzhong, Human Brick, which used 600,000 red paper men cut by craftsmen using needles. (Image courtesy of Central Academy of Fine Arts, cafa.com.ch)

A display at Central Academy of Fine Arts where he teaches had hundreds of thousands of tiny red characters affixed to the ceiling and walls of the exhibition space, an installation measuring 1350cm x 300cm x 500cm. In a further iteration, Lu had immense plastic Chinese coins fabricated (99cm x 18cm) and mounted on old fashioned wooden bases. Filling the plexiglass coins were innumerable tiny red figures. In this way humanity and money were presented in a modern format but appeared as old-fashioned looking artefacts, merging the divide between tradition and contemporary art. 11 Moreover, the red humanoids seemed dwarfed by the coins in which they are contained which could have been a sardonic reference to the all too important role of money in society.

Fig. 3: Lu Shengzhong, The Book of Humanity: Empty Book, 2007. Papercut, Chinese traditionally bound books. Dimensions variable depending on installation, c. measuring 228.6 cm. (Image courtesy of Chambers Fine Art, NY)

Another large-scale installation, originally created for the Venice Biennale of 2003, (though his participation was cancelled due to SARS) 12 was another iteration of Book of Humanity: Empty Book that was on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and elsewhere (Figure 3). 13 On its ceiling, he mounted free-standing scrolls measuring 228.6 cm tall with trails of red paper cutouts. The top portion of each scroll was taken up with a carefully cut circular design within which tiny red figures ran, jumped, and danced. Beneath the central disc were long red trails of images that resembled calligraphy or hieroglyphs from a distance. They were, in fact, the scraps of paper left over from cutting out the top motif. The grandeur of the display awed viewers. But one must consider why the books are empty? Again, Lu chooses to be enigmatic and may be indirectly critical of modern society and the prohibitions against free speech.

Fig. 4: Lu Shengzhong, Face Maze 001, 2010 paper cut, thread on paper with pencil inscriptions. (Image courtesy of Chambers Fine Art, NY)

In sum, Lu increased the range of types of art made of cut paper, filling rooms from ceiling to floor with his red figures. Unlike the auspicious images that proliferate in rural traditions, he found one motif that he routinely employed in a number of formats including books, installations, and even cutout metal sculptures. He has greatly inspired later artists who studied with him at CAFA.

Fig. 5: Lu Shengzhong, Shape and Shadow III, 2007 painted metal 240x180x2 cm. (Image courtesy of Chambers Fine Art, NY).

Fig. 6: Lu Shengzhong, Shape and Shadow, 2002 painted steel 81 x50 x 66 cm. (Image courtesy of Chambers Fine Art, NY)

Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky is an art historian and curator. She teaches at Bard College Lehman College and has published widely on Chinese medieval art and Contemporary Chinese art. For more about her and her work, visit http://www.karetzky.com. Email: karetzky@bard.edu