Connecting the Musical Dots of Cold War Korea: Ely Haimowitz and Kim Sunnam

At 7:30 PM on October 2, 2022, I performed modern Korean composers’ pieces from the 20th and 21st centuries at Carnegie Hall in New York. Music is a powerful tool to express my Korean national identity, and Korean modern composers’ musical grammar communicates with me as a performer. For a long time, my performance repertoire was selected from music by European and American composers from different eras. However, I started to add Korean modern composers’ pieces in 2020. Learning more about my native country of Korea through their musical narratives as well as their personal histories feeds my musical imagination about the colonial era (1910-1945) and the Korean War (1950-1953) that were sources of trauma for Korean people. In September 2022, I did an interview with David Kim, the concertmaster of the Philadelphia Orchestra, who shared his experience of visiting South Korea in the 1980s for the first time with his father. Kim told me he cried on the plane when he came back to the United States because he realized that Korea was his land (ttang) and roots (ppuri). 1 By performing the music of Korean modern composers, I construct my national identity and understanding of Korean history – it has been my journey to find my “roots” as well. The music of Korean composers reflects such “roots” by evoking their traumas and sentiments.

American ethnomusicologist Thomas Turino notes, “The famous European composer Igor Stravinsky is often credited with the idea that music has no meaning beyond itself. He was expressing a notion that is held by some people about music, especially European classical instrumental music, that it is an abstract, socially autonomous art. One reason for this attitude is that it is often difficult to capture or translate musical meaning with words.” 2 For Korean modern composers, their lives and their music reflected the tumultuous modern history of Korea: Japanese colonial occupation (1910-1945), liberation from Japan (1945-early 1950s), and the Korean War (1950-1953). The conflicts of the Cold War hardened after the Korean War divided the country into two separate nation-states: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (South Korea), occupied by the USSR and the United States, respectively, with the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between them. After his visit to North Korea to attend a music concert in Pyongyang in 1990, Korean music scholar No Tongŭn said: “Nothing hurts more than the pain of division.” 3 Korean modern composers’ music narrates their nostalgic sorrow, traumas, hope, national sentiment, and despair, allowing us to imagine what their experiences of the Korean War must have been like. This article explores chaotic Cold War Korea by examining the complicated journeys of Korean modern classical musician Kim Sunnam (1917-198?) and American pianist Ely Haimowitz (1920-2010), connecting the musical dots through their music.

Floridian pianist Ely Haimowitz and Korean composer Kim Sunnam in Cold War Korea

To celebrate independence from Japan in 1945, Korean people came together to sing “Liberation Song (Haebang ŭi norae)” by Kim Sunnam, head of the Korean Proletarian Music Union. The piece evokes the post-liberation era (1945-1948), which is sometimes called the haebang gonggan (해방공간, 解放空間) in Korean, or the “space of liberation.” This gonggan (공간, 空間), which can refer to an empty space with nothing in it, was a chaotic period for Korean musicians. In the post-liberation era, the Korean Peninsula was occupied by the United States and the Soviet Union. In the south, the United States Army Military Government (USAMGIK) tried to establish music education and culture there.

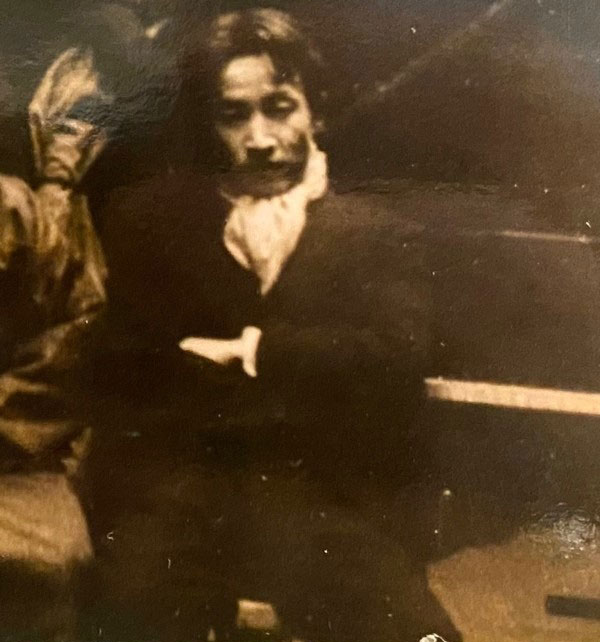

Fig. 1: Kim Sunnam (1917-198?). (Photo courtesy of Kim Sewon)

A Florida native, pianist, and graduate of the Julliard School, Ely Haimowitz arrived in Korea in 1945. Haimowitz was “in charge of music education for the USAMGIK in Korea, 1945-1946, then was made the first cultural affairs officer for the commanding general, US Armed Forces in Korea.” 4 He organized workshops for music teachers and established a music curriculum that included Western music theory and history. 5 Korea’s classical music culture was achieved partially through Haimowitz’s efforts. He helped to organize and raise funds for Korean arts groups and to develop the Korea Symphony. 6 Political struggles brought confusion and instability, but ironically, Korean modern composers created beautiful and experimental music with their patriotic voices. The conductor Im Wŏnsik (1919-2002) and pianist Yun Kisŏn (1921-2013) were the first Koreans to study at the Juilliard School with Haimowitz’s help, and they established Korean music education and classical music culture when they returned to their home country. Haimowitz helped Kim Sunnam receive a scholarship to the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, California. He also showed Kim’s music to Aaron Copland, the American composer, who offered Kim a scholarship to participate in the Tanglewood Music Festival in Massachusetts, but Kim was not able to go to the U.S. 7 The leader of the Korea Musicians’ Coalition, Kim wrote the piece “People’s Protester (Inminhangjaengga)” in 1946 with the lyrics of modern poet Im Insik (Im Hwa, 1908-1953). 8 When the USAMGIK cracked down on the left, an arrest order was issued for Kim as the composer of this song, and he fled to the North in 1948, leaving behind his family in the South. 9 Korean scholar No Tongŭn notes that approximately one hundred Korean classical musicians went to the North – all musicians in their 30s who studied in Japan. Unfortunately, he has not been able to track their work since they defected to the North. 10

Fig. 2: Kim Sunnam’s daughter, Kim Sewon, visited Ely Haimowitz in Reno, Nevada. (Photo Courtesy of Kim Sewon)

In 1952, Kim left North Korea to study in Russia at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory of Music with Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978). He wrote a number of instrumental pieces and songs, but he had to return to North Korea in 1953. 11 Kim’s honor, title, and right to create compositions were taken away in 1955, and his compositions were forfeited. He was purged and sent to Sinpo from Pyongyang to do hard labor because his music was criticized as “bourgeois.” 12 Unfortunately, it is hard to connect the dots of his life in North Korea after he was purged. Some Korean scholars claim that he passed away in 1986, but his daughter received information that he passed away in the early 1980s from pneumonia caught while doing hard labor.

Kim Sewon’s (b. 1945) memories of her father in North Korea: My Father, Kim Sunnam

Kim Sunnam’s “Lullaby (Jajangga)” (1948) is one of the pieces I performed at Carnegie Hall this October. I called Kim Sewon (b. 1945), Kim Sunnam’s daughter in Seoul, from Florida to share this exciting news. Earlier this past summer, I had met her in Seoul to conduct an interview. She is one of Korea’s distinguished broadcasters, and she published the book My Father, Kim Sunnam in the 1990s. Kim Sewon never met her father, who had left for North Korea. She recalls her trips to Russia, China, Mongolia, and Europe to find traces of her father. Kim’s mother and grandmother talked about her father in Japanese so that she would not understand them, but she overheard them talking about her father in Korean late one night when they thought she had gone to sleep. She could not talk about her father for many years, until the ban on music by composers who were kidnapped or defected to the North was lifted in 1988. Kim Sewon still remembers how she was excited to attend a recital to listen to her father’s pieces the first time they were performed in Seoul in public. Korean newspapers had highlighted her life as the daughter of someone who had defected to North Korea, so she described the moment to me as feeling that “the nail in her heart had finally been pulled out.”

Fig. 3: Kim Sunnam’s collection of Korean Art Songs, Lullaby (1948). (Photo Courtesy of Kim Sewon)

Kim Sewon is now 77 years old and is proud to recognize Kim Sunnam as her father. She further told me that her father left two things for her: her name, “Sewon,” and his song “Lullaby” from the collection of Korean Art Songs, Lullaby (Jajangga), which was published in 1948. Korean music scholars assert that this song is for Koreans who were in chaos during the post-liberation era and that he wrote it for Korean people as though soothing a baby. However, his three lullaby songs were also a gift for his only child, the daughter he named “Sewon,” the meaning of her name expressing his wish that she become a beautiful person in the world. Kim wrote another “Lullaby (Jajangga)” in 1950, two years after he had left for North Korea. In the lullaby, he sang from the North to his daughter, who remained in the South at the time: “Sleep well, my baby / [My] proud Partisan’s baby / When new spring comes / [your] father will also come.” 13

Fin

July 27, 2023, is the 70th anniversary of the Korean Armistice Agreement of the Korean War. The conflict between two opposed ideologies not only divided the Korean Peninsula but also separated musicians in the South from those in the North. Due to struggles between political ideologies, some musicians stayed in South Korea and others left for North Korea. I argue that Korean modern composers’ musical works drove the creation of their musical language and led to their music being a dramatic musical diary of these tumultuous times. They were activists and artists, and their music survived amid the tragedy of the Cold War. Korean modern composer Kim Sunnam and American pianist Ely Haimowitz crossed paths in tumultuous times. Kim’s Konzert für piano in D, “Dedicated to Mr. Haimowitz,” survived long after their parting. Haimowitz gave this concerto to Kim’s only child, Kim Sewon, and after a long journey, his music finally arrived in his hometown of Seoul.

On September 9, 2022, my research and questions led me to visit Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, where Haimowitz had studied. There, in a blue folder box, his handwriting, letters, pictures, newspapers, and Korean and English articles preserve Haimowitz’s voice. In one of his letters, Haimowitz writes, "And then in the years to come, even a thousand years hence, men will not remember Korea today for its political problems or leaders or systems alone; they will remember the great achievements of Korea's artists. For we know that human life on earth is short, but its art endures forever.” 14 The chaotic and harrowing layers of history and politics on the Korean Peninsula are reflected in Korean modern musicians’ musical grammar. Regardless of whether these musicians were on the left or right, or in the North or South, their music expresses their Korean roots, and we continue to remember “the great achievements of Korea’s artists,” as Haimowitz wrote.

Dr. Yoon Joo Hwang is an Assistant Professor of Music at the University of Central Florida. Recently, she completed the North Korea Program at George Washington University to expand her research into music in Cold War Korea. E-mail: yoon.hwang@ucf.edu