A Cityscape below the Winds

In July 2021, my book World Heritage and Urban Politics in Melaka, Malaysia. A Cityscape below the Winds was published in the Asian Heritages Series. The publishing process has been a wonderful experience thanks to the Series Editors, the publication teams at IIAS and Amsterdam University Press, the anonymous reviewers, and, last but not least, my Melakan interlocutors and friends. Without each and every one of them, the publication of this book would not have been possible. The book is still fresh, and it has received only one review so far. A quite positive one I must add, and I was glad that it came from an established researcher with an expertise on critical heritage studies in the region. 1

In September 2021, I had the honour to present this work at the first “IIAS Book Talks” webinar. The very first question from the audience concerned the choice of Melaka as case study. As some might know, Melaka represents only part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site “Melaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca.” Let me say that, when I had to select an urban World Heritage Site in Malaysia for my doctoral research, I chose Melaka for two simple reasons. First, it is the city par excellence to unravel the intricacies of the international, national, and local politics of heritage in Malaysia. Melaka is celebrated as the cradle of the nation. Its glorified sultanate (c. 1400-1511) was followed by the Portuguese, Dutch, and British colonial administrations. Because of its importance in the national narrative, Melaka was a priority in the agenda of World Heritage nominations. Second, despite the numerous publications on Melaka, a critical heritage approach was still missing, especially in comparison with its twin World Heritage city of George Town. In 2008, for example, Gwynn Jenkins published a book which explored the sociocultural and architectural history of George Town in light of the World Heritage inscription process. 2 Because Melaka and George Town together constitute a single World Heritage Site, a book on the other half of it – Melaka in this case – hopefully expands the understanding of urban World Heritage politics in Malaysia.

When I started this journey I was interested to know what happens to a city after inscription in the World Heritage List. Fieldwork opened my mind not only to the effects of such a designation in the long term. It also led me to understand how heritage conservation unfolds on the ground with specific reference to processes of “museumification” and “replication,” tourism gentrification, the politics at play in the making of “racialized” tourism enclaves, and urban struggles like the one that the Chetti community was undertaking against a high-rise construction next to its century-old kampung (“village”).

Melaka’s urban development and tourism in light of recent events

Kampung Chetti is a low-rise “heritage village” located just metres away from the World Heritage boundaries. Within the boundaries, limits on new constructions have been introduced to preserve the historical landscape. Nevertheless, Melaka has attracted the interest of developers, who are not constrained by conservation regulations when they seek to build high-rises all around the site. I started to realize the intricacies and asymmetries of heritage hierarchies, which unfold where international/national/local heritage systems as well as ethnic majorities and minorities meet. 3

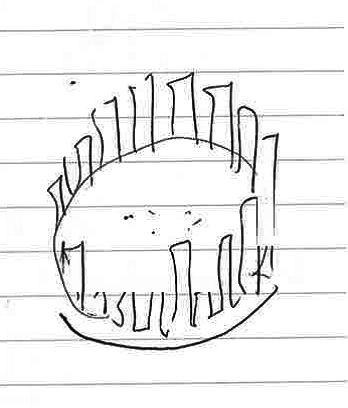

During an interview, one conservation expert sketched a circle. At its center was the World Heritage Site, surrounded by high-rises [Fig. 2]. It represents what he foresaw following the construction boom triggered by the World Heritage status. My interlocutor was frustrated because there was no building height control around the site, and new high-rises were going to affect both the World Heritage landscape and other vernacular neighbourhoods such as Kampung Chetti.

Figure 2: Sketch representing the future of Melaka. (Photo by Pierpaolo De Giosa, 2013)

I returned to Melaka in 2022, after a two-year long border closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the “heritage villages” around the World Heritage Site have their own adjacent high-rises now. Others along the coast are also affected by land reclamation projects that are meant to create new land and artificial islands from the sea. It is along the coastline, in fact, that the predictions of that sketch are most evident. Empty lots downtown are scarce, 4 so land reclamation aims at providing more space for the construction of high-end real estate, hotels, malls, theme parks, and cruise facilities. For example, the M-WEZ (Melaka Waterfront Economic Zone) was launched in 2021 with the objective of transforming a mega-development corridor – stretching for 33 kilometres along the reclaimed coastline – into an “International Investment Destination.”

The M-WEZ promises to attract billions of ringgit from abroad, and to create thousands of new jobs for locals. There are, however, many risks to be considered, especially in light of the recent global pandemic and the local economic and political instability. First, the pandemic has taught us that to rely entirely on tourism and foreign investment is unsustainable. Most of the tourism-related businesses downtown have been badly affected in the last two years, and even well-known hotels have closed down. Second, the pandemic has exacerbated the foregoing slump in the property market. Melaka is indeed affected by an oversupply of residential units, retail space, and hotel rooms. Third, many mega-development projects on reclaimed land have been launched on the wave of enthusiasm for the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, introduced by China in 2013. Companies and investors from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore have been particularly active in this context. This makes sense, given that Chinese and Singaporeans made up the bulk of Melaka’s tourist arrivals before the pandemic. The property market impasse is intensified even more by capital controls or bans that have affected the outflow of money from China, Malaysia’s largest trading partner. Finally, such mega-development projects countertrend local preferences for low-rise landed properties and affordable housing. There is a feeling that Melakans themselves are not going to gain anything, neither in terms of job opportunities nor in the purchase of properties that are mostly targeting foreigners and the well-off. Overall, many Melakans fear that such overambitious projects are not going to materialise. Melaka already has quite a number of failed projects, or “white elephants” as they are locally called, and many think that the M-WEZ will be yet another. 5

Fig. 3: A view of high-rises under construction from St. Paul’s Hill. (Photo by Pierpaolo De Giosa, 2013)

Moving towards other shores

Publishing my first monograph has been a personal milestone, and I am sure it played a crucial role in future research trajectories. When the book was published, I was preparing my application for a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship grant, which I had the good fortune to obtain. So, I am embarking on a new project called “Malaysian Reclaimed Landscapes: Urbanization, Heritage, and Sustainability along the Littoral.” This research will take my interests in critical heritage studies and urban anthropology to other shores, not so far away from Melaka: Penang and Langkawi, where land reclamation projects are being planned. Penang South Reclamation involves the creation of three artificial islands, and Widad@Langkasuka intends to reclaim land in the shape of an eagle, the symbol of Langkawi.

Fig. 4: High-rise under construction beside Kampung Morten (Photo by Pierpaolo De Giosa, 2013)

Many are concerned about the socio-ecological effects for the environment and coastal communities. On the one hand, reclaimed landscapes are being planned for large-scale construction projects, modelled on high-tech fantasies of a luxurious lifestyle in a greener and smarter environment. On the other hand, such projects are intended to transform spaces that represent enduring heritage (e.g., fisheries, seascapes, and biodiversity). Reclaimed landscapes thus emerge as contested spaces where what is not considered heritage becomes attractive for development.

This ethnographic project will explore the ways environmental activism and discourses on sustainability and heritage unfold on the ground, together with the masterplans and compensation policies at work around yet-to-be-built-islands. I will thus conduct fieldwork among a diverse range of actors such as local residents, fishermen, surfers, activists, architects, and academics, but also governmental elites and developers. The project will also involve co-design activities with local stakeholders and the production of a Toolkit in a free-access booklet version. It will based on emic perspectives, creating space for those marginalized voices in spatial planning and development. The project advocates the importance of ethnographic insights for policy-oriented practices in order to make a more sustainable and equitable planet.

Pierpaolo De Giosa is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Asian Studies of Palacký University Olomouc. E-mail: pierpa.degios@zoho.com