From Zarzuela to "Sarswela": Scenes from Filipino Lyrical Theater

The genre of lyrical theater known as zarzuela developed greatly during the 19th century, becoming an important mode of entertainment in Spain. Part of its development occurred thanks to the trips it took to other parts of the Spanish-speaking world. Furthermore, zarzuela reached the Spanish colony of the Philippines, where the most relevant works of the repertoire were played. This form of Spanish lyrical theater (already an adaptation from European operas) coexisted in the Philippines with other performing arts such as European opera and a Tagalog form of popular theater. Local artists were trained to perform the new genre onstage, which, in turn, would later give way to a local creation called sarswela.

The arrival of the zarzuela

In the 19th century, Cuba and the Philippines were the two overseas geographies that remained part of the Spanish Empire after the independence of the colonies in the American continent. This circumstance kept the Philippines in touch with Europe and thus with a great deal of Western artistic expressions. Dramatic and lyrical theater companies performed during this period and made known the current repertoire of the West in the East. The first complete zarzuela staging in the Philippines was El duende [The Fairy], which occurred at the Teatro de Binondo in Manila on February 22, 1851. With a libretto by Luis Olona (1823-1863) and music by Rafael Hernando (1822-1888), it belongs to what is known as a restored zarzuela and was premiered at Teatro de Variedades in Madrid on June 6, 1849. In 1848, a group of political deportees arrived in Manila, among them Álvaro Carazo and Narciso de la Escosura (?-1875), the latter of whom took over the Teatro de Binondo and began to stage works from the Spanish repertoire. On his return to Spain, Escosura encouraged the director of the theater company known as the Teatro del Balón de Cádiz, Manuel López de Ariza, to travel to the Philippines to carry out a few seasons of lyrical and dramatic theater. López de Ariza arrived in Manila in 1852, and naturally, the place where they performed was at Teatro de Binondo [Fig. 1]. They performed a repertoire that included mostly dramatic pieces: Isabel La Católica [Isabel, the Catholic Queen], Diego Corrientes, and some short theatrical pieces by Ramón de la Cruz (1731-1794) of humorous theme and usually of popular characters called sainetes. Additionally, a small work with music was staged: El Tío Caniyitas [Uncle Caniyitas] by Mariano Soriano (1817-1880). In the years 1878 and 1879, two of the most representative zarzuelas were performed in Asia: Jugar con fuego [Playing with Fire] and El barberillo de Lavapiés [The Little Barber of Lavapiés], both by Francisco Asenjo Barbieri (1823-1894). From then on, the history of zarzuela in the Philippines would be linked to the person of Darío Céspedes (?-1884), who, in 1881, created a zarzuela company at the space known as Coliseo Artístico, merely a kiosk that was suitable as a performance theater in the area known as Arroceros.

As press reviews from this period demonstrate, the most important titles of the Spanish zarzuela began to be known in 1855, when Los diamantes de la corona [The Diamonds of the Crown] by Barbieri premiered in Tondo, and Emilio Arrieta’s Marina began to be played in 1860. It is significant that in 1877, the performing of Arrieta’s El Potosí submarino [The Submarine Treasure], shows the presence of the Spanish teatro bufo – a genre of popular satirical musical theater transplanted from France to Spain by Francisco Arderius (1835-1886) in 1866 – into the insular repertoire. One of the best-known anecdotes around zarzuela in Manila concerns Guillermo Cereceda’s Pascual Bailón [Pascual the Dancer]. It turns out that the “daring” dance scene performed in August 1886 (the French can-can) caused a reaction from the church, whose top representatives published a press note criticizing the performance.

A second breath for the zarzuela

The second phase of the zarzuela began in 1881 with the arrival in Manila of two Spanish artists who had made significant careers in the theaters of Spain: Alejandro Cubero (1825-1888) and Elísea Raguer. Cubero worked in the Philippines from April 1881 until March 1887, establishing one of the most important periods of the zarzuela in the Philippines. He died in Spain at the beginning of 1888. With the return of Cubero and Raguer to Spain, this episode came to an end, although Raguer returned to the Philippines in March 1888 and stayed until 1897, when she returned to Spain permanently. Not only they performed new plays, but they also helped professionalize Filipino actors and actresses that already had a certain career on the stages of the time. These included Práxedes Fernández, Patrocinio Tagaroma, Nemesio Ratia, and José Carvajal, among others.

Práxedes Fernández de Pastor (1871-1919), better known as Yeyeng, began her career at a very young age. She joined the Cubero’s troupe and later organized her own company called FERSUTA, using the first syllables of three of its members surnames (Fernández, Suzara, and Tagaroma). On August 12, 1894, on the eve of her marriage to Ricardo Pastor y Panadés, she said goodbye to her audience at Teatro Zorrilla in Manila with a performance of Edmond Audran's La Mascota [The Mascot]. On August 18, she married and moved to Iloilo, where she lived until March 1899. After spending the next three years in Spain, she returned to Manila in February 1902. She was highly appreciated by the Filipino public and in the first two decades of the 20th century, she maintained the presence of the Spanish zarzuela and introduced the Viennese operetta, with plays such as The Count of Luxembourg and The Merry Widow. Patrocinio Tagaroma (1874-1926) also began her theatrical career at an early age. When Yeyeng married and retired from the theater, Tagaroma became the favorite of the public. Nemesio Ratia (1854-1910) was the only Filipino actor to seek a career in Spain. In March 1889, he embarked for Barcelona, later going to Madrid. On September 17, 1889, he had his debut at the Teatro Felipe in Madrid with El lucero del alba [The Morning Star]. By November of the same year, he returned to Manila, appearing at the Teatro Filipino on December 22. José Carvajal (1862-1928) was a Spanish mestizo who became notable as a comedian. On February 8, 1904, at Teatro Zorrilla, he premiered the zarzuela Ligaya, which he authored. At that time he became the director of the Hispano-Tagalog Theater Company. He also worked in the Company of Fernández Pastor. What Yeyeng became as a female performer, he achieved as a male. He was called the Prince of Filipino artists. It is possible to affirm that these two performers were the ones who continued the tradition of Spanish lyrical theater in Asia and made possible the transition to what would later become Filipino sarswela.

The creation of local plays

Among the development of lyrical activities, evidence of an artistic syncretism started to occur. Some texts of zarzuelas began to be translated into Tagalog, such as Buenas noches, Sr. Don Simón [Goodnight, Mr. Don Simon]. Apparently the first such translation into Tagalog, it was performed at Teatro de Tondo in February 1854. One year later, El duende was also performed in the Teatro de Sibacon. The zarzuelas that were showing during the second half of the 19th century were mostly works composed in Spain. But the zarzuela genre was so well received that some playwrights and musicians who settled on the islands began to compose works in Spanish with Filipino themes and characters. These local elements included a genre of traditional Filipino love song written in Tagalog, known as the kundiman, as well as texts in languages such as Tagalog or Chabacano.

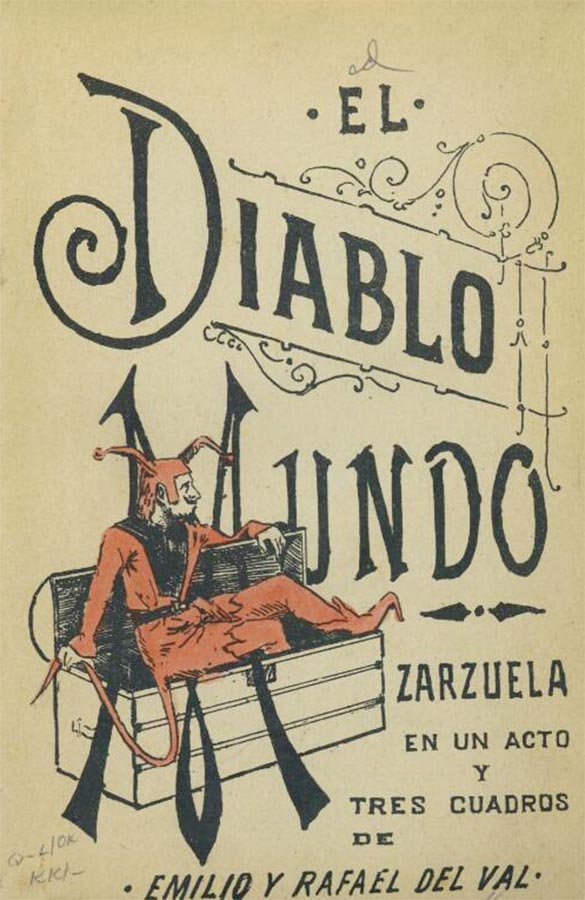

The number of zarzuelas translated into Tagalog accompanied by vernacular music increased, but so did the number of local plays written and performed in Castilian. Salir a tiempo de pobre [Get Out of Poverty in Time] by Antonio Robles made its debut at Teatro de Binondo on May 18, 1852. Other outstanding zarzuelas written in Spanish from the Philippines included El viaje redondo [Round Trip], a one-act piece written in verse by Regino Escalera and Federico Casademunt with music by Ignacio Massaguer (Teatro del Circo in Manila, December 12, 1878); Cuadros filipinos [Filipino Scenes] by Francisco de Paula Entrala, which pointed out the excesses of Tagalog comedy and was premiered by the Alejandro Cubero’s company in 1882; Una novia de encargo [A Custom Bride] in one act and in verse by Ricardo Castro Ronderos with music by Alfredo Goré (Teatro Filipino, March 1, 1884); and El diablo mundo [The Devil World], also a one-act piece by Emilio and Rafael del Val with music by José Estella (Teatro Zorrilla, October 25, 1893) [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2: El diablo mundo front page. (Source)

There were also plays in Spanish which premiered outside of Manila. Such is the case of the following piece (whose subtitles were even longer than the main title): A 7 con 7 el pico o La llegada del “peso insular” y el fin de los contratos usurarios [To 7 with 7, or The Arrival of “Island Pesos” and the End of Precarious Contracts], which was performed at the theater of Iloilo on March 22, 1896. The main title of this piece refers to seven Mexican pesos with seven Spanish reales, and pico was a unit of weight equivalent to 63 1/4 kilograms. This zarzuela is about the introduction of the island peso, or Philippine peso, an initiative implemented in 1896 by Minister D. Tomás Castellanos. The plan was meant to get rid of the Mexican peso, whose widespread presence caused a deep economic crisis in Philippine trade. At the end of the play, the Mexican peso, impersonated by an actor, is kicked out by the island peso and other allegorical characters.

In addition to zarzuela, there were theater performances in Spanish accompanied by music organized by arts and culture associations. Perhaps the best known example is the interpretation of José Rizal’s piece Junto al Pasig [Next to the Pasig River], a short piece composed on request, to be performed by students of the Ateneo de Manila and staged at 6pm on Wednesday, December 8, 1880, at the academic institution. The few musical interventions that appeared in the performance were composed by Blas Echegoyen.

What is relevant about these works is the intention to include Filipino characters, situations, and customs, as well as the mixing of words and expressions in vernacular languages in the dialogue and the combination of Western musical genres and local ones. During this period there were many plays which did not include musical parts, but still tried to expose the diversity of Filipino society.

Local customs and practices

One of the peculiarities of zarzuela in Asia has to do with the general organization of the performances. This varied from paying homage to the actors to changes according to the weather conditions. The función de beneficio, for example, was a special performance designed to show admiration and support to the actors by providing them with splendid and lavish gifts offered by the public or government authorities. Additionally, there were the “hooks” to attract attendees, which consisted of either organizing raffles at the end of the show or providing free transportation if the theater was far from Manila, in a suburb of Tondo, for instance. This was especially important because performances used to end late at night.

Shows were also subjected to the weather conditions. Theater organizers arranged a practical communication system when it came to climate contingencies: if the performance was suspended because of bad weather, the public were notified by means of a red lantern placed at the top of the theater’s flagpole. Additionally, a white lantern was placed on the two bridges over the Pasig River, the Puente Grande (later renamed Puente de España) and Puente de Santa Cruz. The former connected the areas of Binondo and Ermita, while the latter connected Ermita and Santa Cruz. Those on their way could find out before arriving to the show (crossing the river) that it had been cancelled.

The Teatro de Variedades in Manila had a particular building structure which made it possible for people to hear the show from outside. Consequently, those who did not enter for some reason, could stand and listen in from the outside without having to buy a ticket. The theater organization instructed the doormen to ask people to keep walking in order to avoid crowds outside the theater.

Filipino sarswela

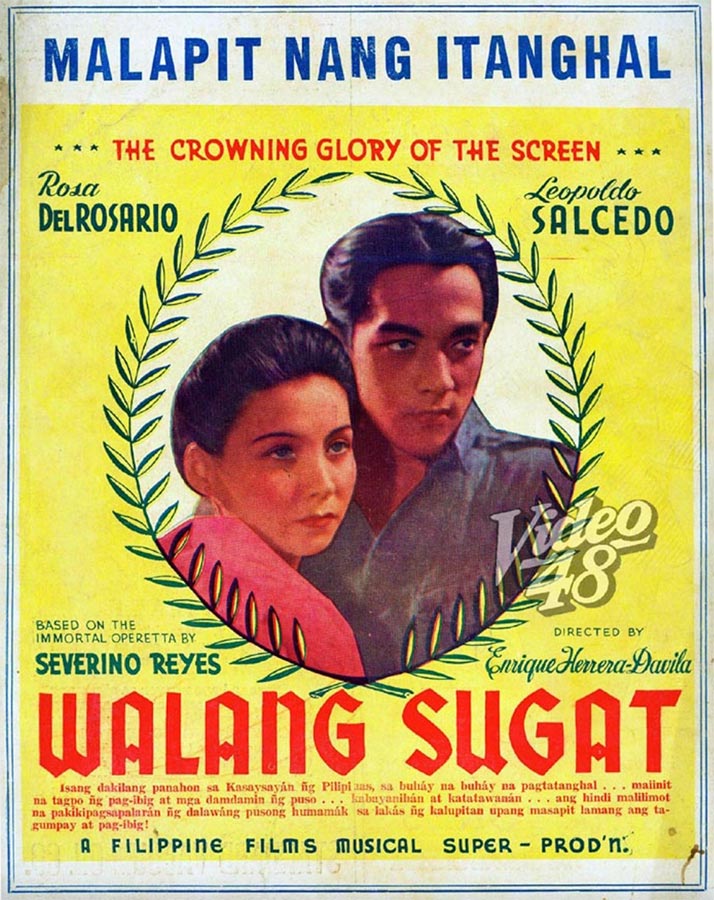

In 1898, the Philippines ceased to be part of the Spanish Crown. With the beginning of a new century and the US occupation, the growth of a new identity began. In this quest for a national character, the community of theater people (singers, composers, musicians) were committed to incorporating the Tagalog language more assiduously in their works. The radical change was to compose works in Tagalog, within the format of the Spanish zarzuela, whose plots portrayed and reflected the sociopolitical discourses of the moment. This resulted in a syncretic genre called sarswela. Outstanding works thus emerged, such as Walang Sugat [Without Wound] by Severino Reyes (1861-1942) with music by Fulgencio Tolentino (1872-1940), which premiered at Teatro Libertad in Manila in 1902. Another was Dalagang Bukid [The Country Maiden] in 1917, featuring a libretto by Hermogenes Ilagan (1873-1943) and music by Leon Ignacio (1882-1967). Dalagang Bukid would later become the script for what has been considered the first Philippine feature film: a silent film of the same title, accompanied by subtitles in English, Spanish, and Tagalog. It was directed by José Nepomuceno (1893-1959) and released in 1919. Walang Sugat was made into a feature film in 1939. It was directed by Enrique Herrera-Dávila [Fig. 3].

With the arrival of new musical genres such as jazz and other artistic tendencies in the second and third decades of the 20th century, a genre from vaudeville, locally known as bodabil, began to take shape in Filipino theaters. Its best representative was Luis Borromeo (ca.1879-?), better known as Borromeo Lou, who since the early 1920s promoted the genre. The bodabil consisted of short light plays that interspersed singing, dancing, and comedians, whose purpose was merely to entertain and expand the type of leisure activities on offer for the population. Its political potential was also diminished. Unlike the sarswela, which could contain political manifestos and social criticism, the bodabil did not cause concern as a politically subversive activity. This new theatrical form and the commodification of cinema, which led to a notable increase in the number of theaters and to the transformation of existing theaters into spaces for film screening, brought an end to the sarswela, a Western pilgrim genre that was able to find its own voice in the East.

Mario Roger Quijano Axle works as professor and researcher at the College of Music at the Universidad Veracruzana (Mexico). His areas of study, along with Mexican music, are French and Spanish music of the 19th and 20th centuries, opera and zarzuela, and artistic and cultural exchanges. Email: mquijano@uv.m