Waste in contemporary Chinese art. Byproducts of China's urban development and consumerism

Waste has made a presence in contemporary Chinese art since the beginning of the 21st century, either incorporated into installation artworks, as the content of photographs or paintings, or featured in documentary films. This artistic trend simultaneously reflects and warns of the rapid accumulation of waste brought about by China’s embracement of global consumerism and urban-focused development. Analyzing different approaches adopted by a number of artists who deal with waste, this article explores the criticality embodied in their works that help raise awareness of the increasingly severe social and environmental consequences.

Phoenixes rising from the waste

Xu Bing (b. 1955), a leading contemporary Chinese artist, completed a large installation piece entitled Phoenix Project in 2010. It consists of two gargantuan sculptures of the legendary phoenix, one 100 feet long and the other 90 feet long (fig.1). The romantic connotations of this creature, however, are contrasted with the hard reality that contributed to their creation, since the two mythical birds are made entirely of building waste and tools that Xu collected from construction sites, which are ubiquitous in contemporary China with its endless process of urban development. These recycled materials include shovels, hard hats, bamboo scaffolding, steel rebar and scrap iron, extinguishers, jackhammers, pipes, tire rims, saws, screwdrivers, pliers, plastic accordion tubing, among other countless items that were painstakingly arranged to form the body, feathers, and talons of the creatures. The industrial construction gives the birds a solid and punitive stance as they rise into the air. Yet as night falls, their mythical quality appears when LED lights laced all over their bodies create an ephemeral and twinkling manifestation.

This work directly engages with the mainstream social discourse in contemporary China, the consumption-oriented urban development. Xu began this work in early 2008 when he was invited to create a piece of public art for the atrium of the World Financial Center in Beijing, which was then under construction. Upon visiting the site he was shocked by the primitive working conditions in which migrant workers labored; they posed a striking contrast with the ultra-modern lifestyle that the extravagant building symbolised.1 In response, he constructed his public installation with recycled waste materials and tools collected from the very construction site it was to be installed, and he hired migrant workers to assist in his project. This was an unusual time, just a few months before the global financial crisis would take its toll, and also the time when the Beijing government implemented tighter controls over cultural production in the city to insure a ‘harmonious’ image of Beijing and China for the international audience in anticipation of the upcoming summer Olympics. In accordance, the building’s developers withdrew their financial support for the work, due to financial constraints but probably also out of concern towards the potentially controversial meaning that the birds might convey to the Chinese authorities.2 Xu continued on his own and completed the Phoenix Project in 2010. The grand scale, the raw appearance, and the process that was modeled upon Beijing’s urban redevelopment, won the Phoenix Project the reputation of “an artwork almost too vivid in its resemblance to contemporary China.”3

In this work, Xu intends to draw attention to both the workers who built the two phoenixes, the demolition of old neighborhoods and the construction of new urban structures such as the World Financial Center that are regarded as more suitable for Beijing’s metropolitan image. Demolition and construction are major sources of the skyrocketing accumulation of waste in the country. This, added by waste produced by an increasingly affluent and rapidly growing urban population, led to China surpassing the U.S. in 2005, becoming the world’s largest municipal solid waste generator.4 Practically, waste has become an unavoidable sight in and outside of Chinese cities and has caught the attention of many critical-minded contemporary Chinese artists.

Xu Bing’s Phoenix Project exemplifies a growing trend among contemporary Chinese artists who seek to engage with various problematic byproducts of China’s GDP-driven and urban-focused consumerist development strategies. Their works open up various forms of ‘civic politics’, a term adopted by Chinese art critic Wang Nanming in his discussion of Chinese socially engaged art, thus contributing to the growth of bottom-up civic public space.5

Waste as an aesthetic object

Xi’an artist Xing Danwen (b. 1967) might have been one of the first contemporary Chinese artists to turn her attention to the increasing presence of waste in China. Her photographic series disCONNEXION (fig. 2), completed in 2002-2003, takes as its subject matter industrial electronic waste, known as ‘E-trash’, that developed countries have dumped in China. Every year, thousands of tons of electronic trash are transported from America, Japan, Korea, and other developed countries, to southern coastal regions such as Guangdong and Fujian, where they are sorted and recycled. According to a recent United Nations report, China is currently the largest e-waste dumping site in the world.6 During her field research in Guangdong Province, one of the most developed regions in China, Xing discovered that thousands of local and migrant workers made a tough living by sorting out mounds of computer and electronic trash in primitive and unprotected working conditions. These waste pickers were exposed to various toxic substances as they tore apart discarded electronic appliances, and during the process they also seriously polluted water and soil in the surrounding areas and beyond, and indirectly contaminated local agricultural produce.7

Xing’s approach to this distressing reality, which had apparently been going on without much public attention in the shadow of spectacular economic success in this part of China, was aesthetic abstraction. Rather than exposing the abhorred working conditions, she photographed the products of strenuous and long hours of labor: mounds of circuit boards, plastic cords, silicon chips, and other electronic components. She gave each mound a close-up shot, capturing disparate shapes and colors of fragmented mechanical products. Her aestheticizing of the cold and lifeless scrap turned them into provocative and enticing images. Their semi-abstract and aesthetically intriguing appearance simultaneously draws audiences in and surprises them once they realise what has been photographed. In a twisted way, these images constitute a distinctive portrait of the downside of China’s rapid development that, in Xing’s words, “conveys the immensity of the problem as well as the unbearable details I witnessed in these e-wastelands.”8 Titled disCONNEXION, ironically relating to electronic products’ purpose of facilitating connection, the work reflects the socio-cultural disconnection between different social groups such as producers of electronic goods, consumers of them, and the trash pickers who also deal with them, in an increasingly atomized contemporary society. The aestheticization and abstraction of the otherwise formidable reality becomes Xing’s unique way of revealing a dark side of globalization and exposing an ugly truth behind China’s rapid development.

Jiangsu-born multimedia artist Han Bing (b. 1974) also used waste as his object of aesthetic contemplation when he made rubbish-ridden rivers, a by-product of China’s consumerist urbanization, the topic of his art.9 He was drawn to the appallingly visible contamination of above-ground water throughout China as a result of the mindless and irresponsible disposal of everyday trash, and began his multiple-year photographic series Urban Amber in 2005. The photo Urban Amber-Red Flags Flying on Skylines Cranes (2006), taken in Beijing, presents a bluish green body of water where one sees water lilies and fallen leaf-like objects floating above a forest of construction cranes with red flags flying overhead, a prevailing sight in China’s accelerated urban expansion. At first glance, the image looks exquisite, giving the illusion of an attractive water surface covered by foliage and animated by swimming fish beneath. Looking closely, however, one realises that it is waste such as garbage bags, plastic bottles, and human sewage that make up the water’s surface. The bluish-green color itself is the result of the water being heavily polluted by putrid rubbish and masses of algae. In other pieces from the series (fig. 3) we see reflections of various man-made structures, such as glamorous skyscrapers and new residential complexes for the rich, shanty dwellings for the urban poor, migrants and peasants, and commercial establishments and advertising billboards, all indistinguishably shrouded under a body of water infested with filthy rubbish.

In this conceptual work, Han took photos of many heavily polluted bodies of water in Beijing and produced single-exposure images without any modifications other than simply turning them upside down. However, it is with such a witty and perceptive reversal that the rubbish thoughtlessly thrown away by people has returned, taking up position in the sky of Han’s landscape. In this series, Han brings to the forefront the paradoxical result of industrialization and reveals a prominent downside of Chinese urbanization. Chinese cities have built higher and higher structures to house the dreams of urbanites, as these construction cranes are still doing in Han Bing’s photo. Simultaneously, the modernized urban lifestyle that centers on material consumption and convenient living has produced ever dirtier and stinkier rivers, ponds, and lakes. Han’s seemingly charming portrayals of the garbage-infested rivers function like amber, which was well put by art critic Maya Kovskyaya: “capturing the sediment of an age, and reflecting the dark side of dreams of modernization.”10

Waste as a component of living space

While some contemporary Chinese artists imbed their social critique in an aestheticizing approach, by presenting the unexpected beauty of waste in their close-up images, others seek to contextualize the presence of waste and directly depict its impact on social space and human existence. Sichuan painter Liu Xintao (b. 1968) captures the invasion of trash in urban public spaces in his Collapsing Night, a series of oil paintings that he has concentrated on since 2005.11 In Collapsing Night-Wild Lily that Liu completed in 2007 (fig. 4), the canvas confronts the viewer with cluttered trash conspicuously taking up the foreground near a street manhole. Amid the scattered trash of unrecognizable objects, some blossoming white lilies emerge. They, however, are rotting like the trash surrounding them. In the middle ground we see the upper bodies of a hugging couple, one of whom is topless while the other’s condition is ambiguous. The love between humans is exposed in the littered street and acquires an incongruous nature.

Behind this all is a wide paved road receding dramatically and submerging into a well-lit area in the distance. This rational and well-ordered section of the cityscape, pushed into a thin slice at the top of the canvas, is in noticeable contrast with the irrational presence of the trash and the hugging pair. Liu describes, as follows, his experience of absurdity in real life that inspired this painting series: “I took a walk at the early evening and what I saw were wild dogs barking, rats scurrying, and stinking garbage piling up here and there. Behind such a messy environment the profile of a thriving city suddenly appeared in distance with its shining and intoxicating neon lights. It was an extremely absurd and even horrific scene”.12

The dominance of the trash in the composition hints upon the wasteful lifestyle promoted in an increasingly consumption-oriented urban culture. A rising urban middle-class who benefits from China’s economic reforms is accustomed to a lifestyle that over-consumes and discards the unwanted with abandon. The composition also points to the way contemporary Chinese urbanites treat or abuse public spaces. Since the 1990s, as art historian Wu Hung has commented, there has been a strong disparity between the care Chinese urbanites attend to their private space and their total disregard for what they consider public space.13 This contrast, I argue, reflects a general decline of social conscience and sense of responsibility among the Chinese population. The source of this problem, one may argue, is the rising dominance of self-interested materialism and a consumption-driven culture, which lacks the effect of moral restraints, like the traditional Confucian ethos or Communist ideology used to have on Chinese citizens. Essentially, it is also a reflection of the lack of their active participation in public space, a problem attributable to the authoritarian approach that denies the right of ordinary citizens to participate in the development and transformation of their cities.

The problem with garbage is also what motivated Shandong artist Wang Jiuliang (b. 1976) to initiate his sociological survey, which locates and documents landfills used for Beijing’s waste.14 He has taken hundreds of photographs, of often disheartening visual content, which show both the natural environment and human beings negatively impacted by the rapid increase of urban waste production. Dominated by the ideology of consumerism, accompanied by rapid urban expansion and increasing affluence, Chinese cities have generated ever more waste in various forms, such as everyday household garbage, electronic and industrial rubbish, or construction and demolition debris.

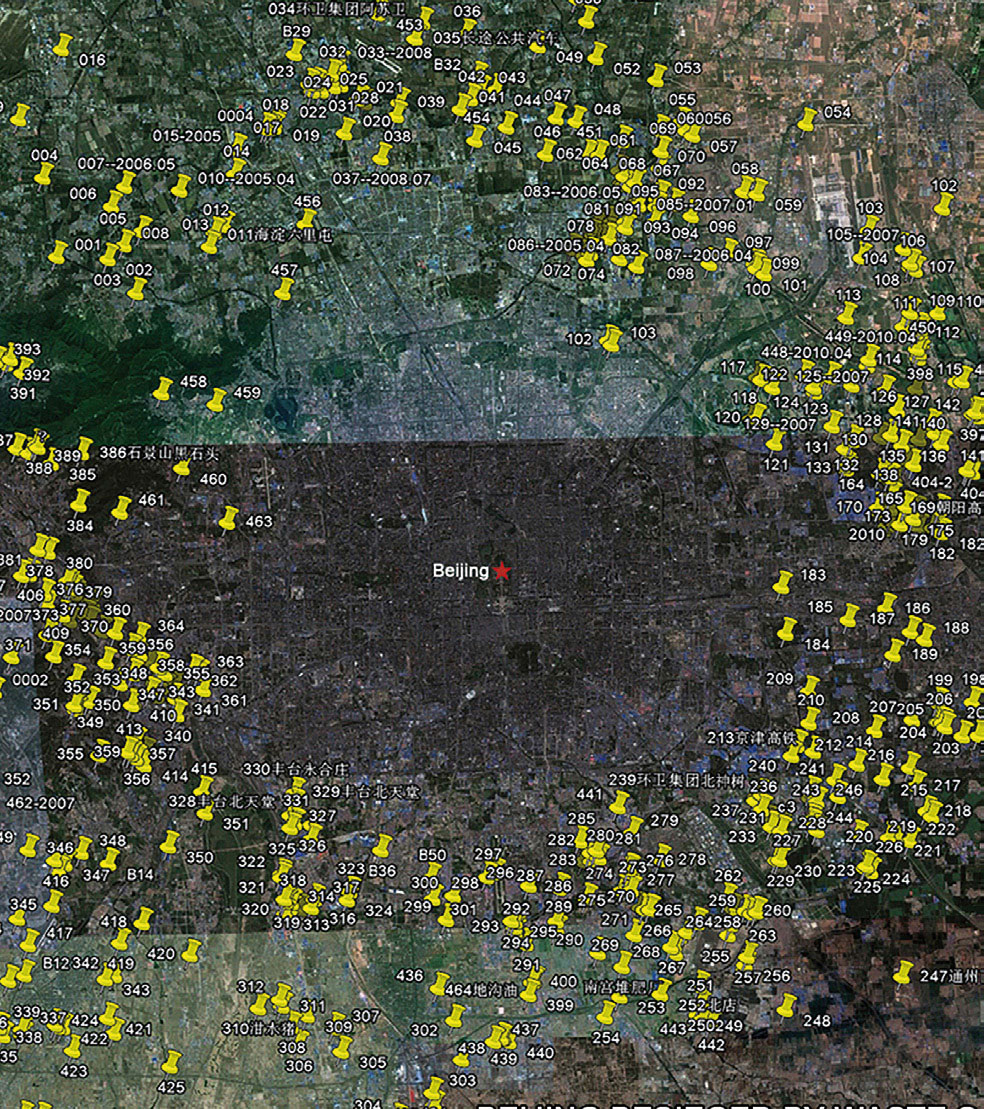

In 2011, Wang released his first documentary, entitled Beijing Besieged by Waste, which combines photographs and video footage of many large landfill sites on the outskirts of Beijing (fig. 5), and of the scavengers, mostly migrant workers from the countryside, who live near and on the dumps.15 Wang mapped the locations of more than 500 landfills surrounding Beijing, and this documentary is a striking summary of his discoveries in the hitherto unseen dirty backyard of China’s capital.16 The 72-minute video narrates Beijing’s distressing cycle of consumption, the ill-managed and sometimes illegal operation of waste disposal, the appalling destruction of the environment including rivers, soil, and air, the horrific lives lived by scavengers and their children, and government negligence or implicit collaboration.

Wang’s film shows how, in order to meet the insatiable demand for construction materials as thousands of new buildings are added to the city’s urban landscape, workers dig deep into mountains and rivers to excavate stones and sand. The numerous pits left behind are used as ready-made landfills into which tons of urban waste are poured. Many of these operations are illegal, but continue nevertheless. On the flip side of this rapid urbanization and rising consumerism, is the bleak and liminal existence of thousands of scavengers, who try to thrive at the lowest level of Chinese society by sorting and recycling waste. Wang’s film takes us into the everyday lives and mentality of these people who live in shabby shelters built from recycled materials, and whose clothes and sometimes food are sourced from the dumps themselves. There, children find toys that their parents would not be able to afford.

Overall, Wang’s photographs and his documentary expose this dark reality existing side-by-side with a world-class city populated by glistering skyscrapers and embellished with iconic architectural projects from internationally famed architects. As his research reveals, the continuous urban expansion, the growing materialism and consumerism, and the negligence from both the municipal government and urban residents seem to have pushed China’s capital city to the edge of self-suffocation with the hundreds of landfills forming a thick belt encircling the city proper.

Civic politics

The increasing presence of waste in art speaks to the omnipresence of waste in contemporary urban society. Accompanying apparent prosperities, brought about by China’s spectacular economic development and nationwide urbanization in the past two decades, is the astonishing accumulation of garbage. Artists such as those discussed above are keenly aware of this problem and in their art they examine waste in its various forms and conditions; they have developed new concepts, methodologies, and aesthetics surrounding waste. Their creative interpretations and realistic representations of waste endow this lowly material a unique role of criticality and make visible its invasive presence, exposing waste as a phenomenon largely ignored in the state-controlled mainstream media and cultural production until recently. As such, their efforts contribute to the growth of ‘green public sphere’, a term coined by environmental scholars in their discussions about China’s rising environmental activism.17

Moreover, the works produced by these individual artists could be seen as ‘parallel structures’, a concept advanced by Vaclav Havel in his call for individuals to engage in small-scale work and politics from below to challenge the totalitarian dictatorship and create a better society.18 Resonating Havel’s political ideas is Chinese art critic Wang Nanming’s adoption of ‘civic politics’ as a useful concept for discussing the work of contemporary Chinese artists who engage with social problems and accentuate the power of artworks to stimulate civic awareness and create new, albeit small-scale, public spheres.19 Wang argues that ‘civic politics’ is different from the grand and centralized top-down politics, and defines it as multilateral, thriving on everyday practice.20 He thus recognizes the importance of various individual-based and different approaches adopted by artists who assume a critical attitude towards Chinese urban reality.

In a post-totalitarian but still authoritative regime of China, these ‘parallel structures’ of artworks challenge the official portrayal of China’s economic development and urbanization, which centers on magnificent cities, glittering skyscrapers, and lavish shopping malls. They constitute various forms of ‘civic politics’ that help to uncover a hidden truth concerning the byproducts of mainstream socioeconomic transformations and open up space for doubt and reflection of the very process. Essentially, the significance of these artworks lies in their potential to contribute to the growth of bottom-up civic consciousness and public space.

Meiqin Wang, Associate Professor of Art History, California State University Northridge (mwang@csun.edu).