A virtual exhibition for remote times

Tangential Stress 2020

14 May 2020 - ongoing

Museum of Nepali Art (MoNA), Kathmandu, Nepal

https://360mona.com

In early 2020, the Museum of Nepali Art (MoNA) was preparing for its grand opening, just as coronavirus grew increasingly ominous worldwide. The museum’s permanent collection of contemporary and traditional Nepali art would have to wait until October 2020 to welcome the public. In the interim, MoNA’s curator commissioned 19 Nepali artists to produce works dealing with the socioeconomic, ecological, psychological, and emotional impacts of the global pandemic. ‘Tangential Stress’ is the result; a free, fully virtual exhibition showcasing artwork depicting the multiple ways COVID-19 has transformed life in Nepal and around the world over the past year.

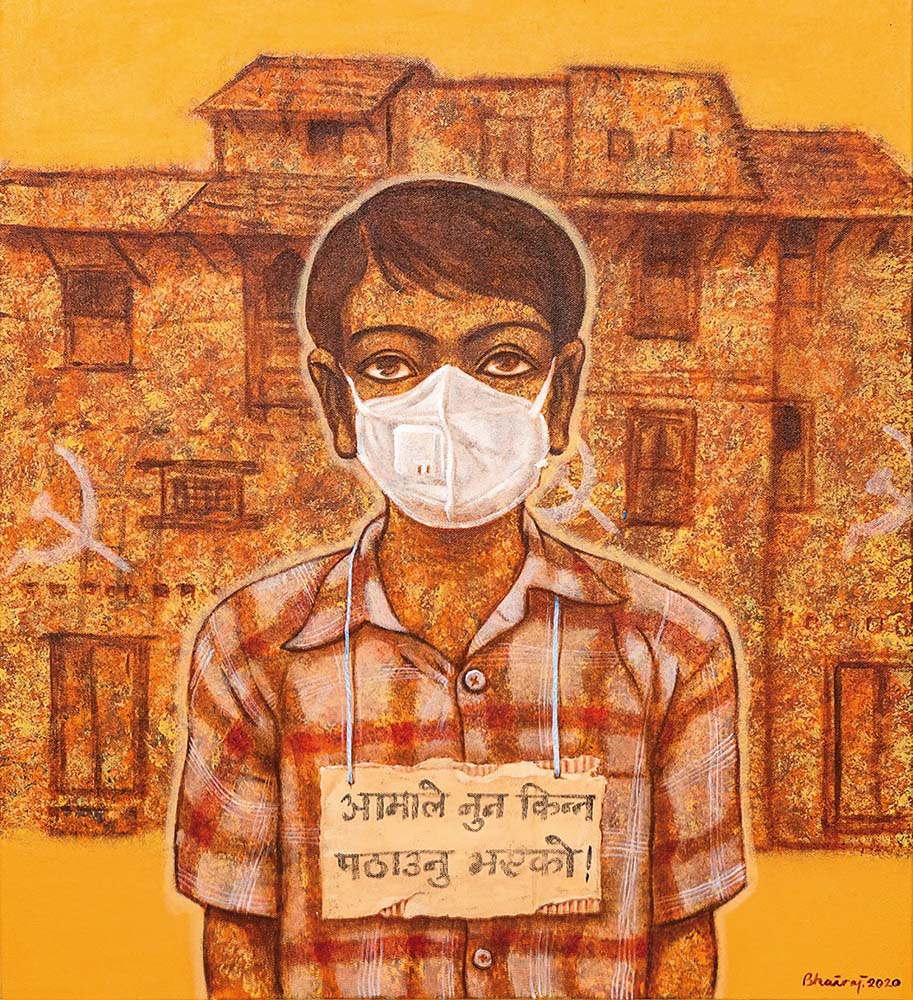

Fig. 1: Powerlessness, by Bhai Raj Maharjan

The Museum of Nepali Art (MoNA)

The Museum of Nepali Art (MoNA) finally opened its doors after eight months of delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequent lockdowns. The new museum is housed on the grounds of the Kathmandu Guest House (KGH), one of the most iconic hotels in Nepal. The MoNA – curated by Rajan Sakya, CEO of the KGH Group of Hotels – aims to create a platform for Nepali artists working in a variety of media and styles. It dedicates a space for the public appreciation and dissemination of Nepal’s artistic heritage. The country has a long, rich history of creative production: Hindu devotional art, Thangka and Paubhā paintings, world-renowned statuary, meticulous woodwork, and more. Such traditions continue today, alongside modern artists working in more contemporary styles. Nepali artwork often hangs in private collections abroad or in foreign museums, such as The Rubin in New York City. Meanwhile, art that remains in Nepal often fails to reach a wider audience. The Museum of Nepali Art seeks to redress this, keeping Nepali art in the country and offering a committed space where the public can experience it.

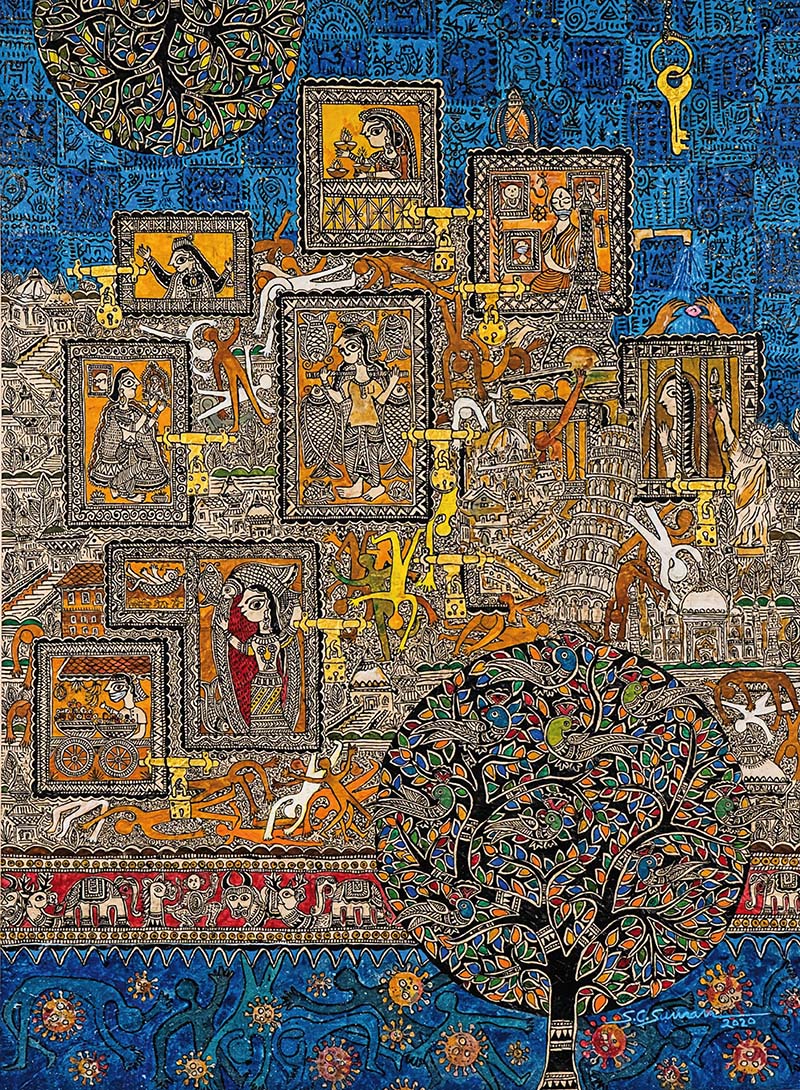

Fig. 2: Mahakala - Destruction with cause, by Rajani Sinkhwal.

The MoNA originally scheduled its grand opening for February-March 2020, precisely the months when the scale of COVID-19 was clearly becoming a threat. The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a veritable pandemic on March 11, and Nepal imposed a nationwide lockdown on March 24. The MoNA’s permanent collection of art (religious and secular, traditional and contemporary) would have to wait. The museum, however, quickly shifted gears. Its curator commissioned 19 works by Nepali artists, each addressing pandemic conditions in Nepal. These were swiftly arranged into a digital exhibition entitled ‘Tangential Stress’. The virtual interface simulates a walk through the manicured grounds of the Kathmandu Guest House, punctuated by icons representing pieces of art. It launched in May 2020, making it among the earliest exhibits focused on the virus’ impacts, and the first virtual showcase of its kind in Nepal.

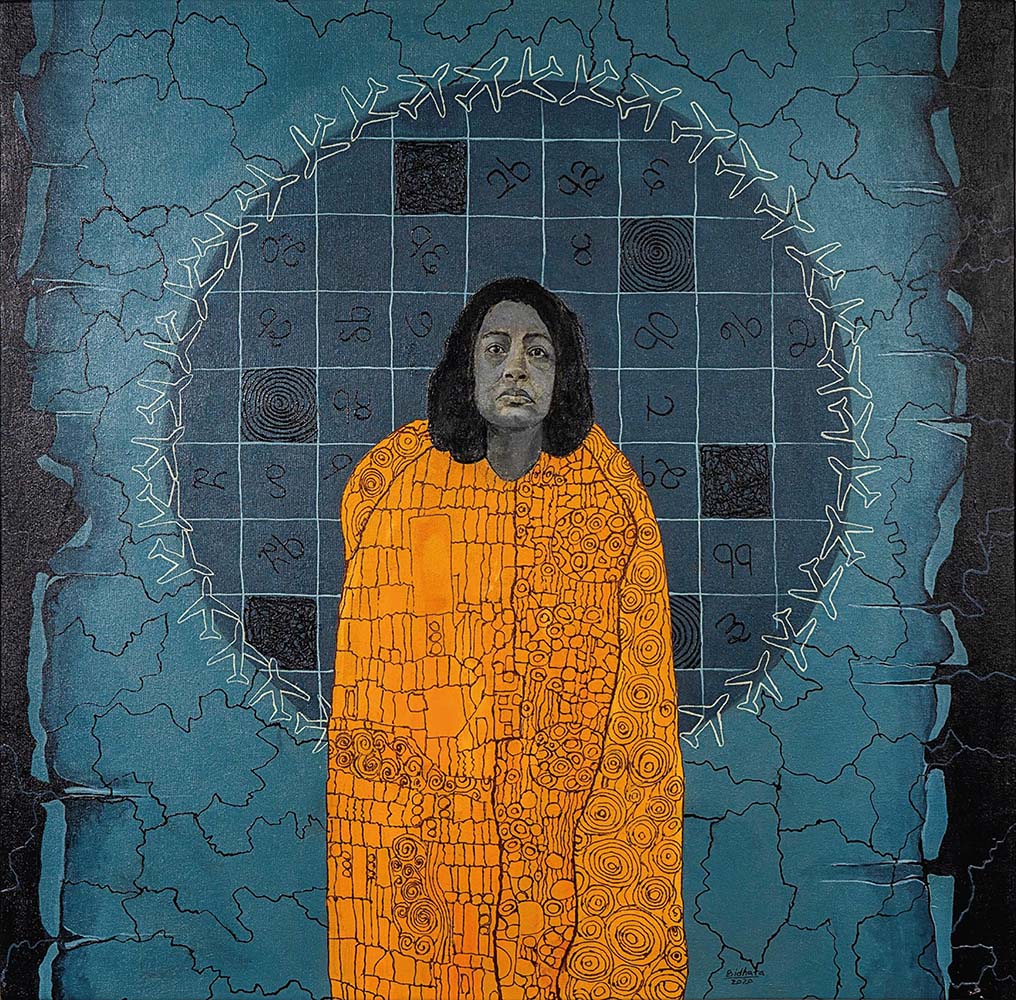

Fig. 3: Your life before mine, by Pramila Bajracharya.

‘Tangential Stress’ in Pandemic Times

The art of ‘Tangential Stress’ is diverse, though all of it hinges on the epidemiological, psycho-emotional, and socioeconomic effects of COVID-19. Several of the pieces take a more expansive view of such effects, depicting the resurgence of nature as humans stayed home, and/or highlighting human perseverance in the face of a biological threat. Sagar Manandhar’s Creativity Never Dies – composed of abstract flashes of color surrounding the fluid shapes of the world’s continents – is a testament to the persistence of creativity and nature during these trying times. Koshal Hamal’s Art in Lockdown depicts a line of multicolored flowers winding in sharp turns up a bright green canvas, with the blossoms representing the experiences and memories that comprise a life. Asha Dangol’s New Avatar evokes the Newari Paubā style, depicting a deity with five heads: the artist and his wife, but also a pig, buffalo, and cow. Behind the figure, viral particles float above a bright blue Earth, hinting at and hoping for a different ecological future. Similar themes emerge in Prithvi Shrestha’s A Game, an inventive self-portrait of the artist, wearing a facemask, surrounded by signs of nature’s reassertion.

The now-ubiquitous shape of the SARS-CoV-2 particle, with its signature ‘crown’ of spike proteins, appears in many of the works on display. Sunita Rana’s आशा (Hope) has an upbeat, vibrant color scheme in which a human figure emerges from, or perhaps is submerged within, a flood of bubbles and virions. Pradip Kumar Bajracharya’s So Small Yet So Big!!! depicts ethereal bodies sprawled and tangled beneath enormous renderings of coronavirus particles. The virions loom menacingly above the faceless bodies. The virus, normally invisible, is thus made to feel commensurate with its outsized impacts. Such impacts include economic and geopolitical disparities shaping unequal pandemic outcomes, themes taken up strongly in Binod Pradhan’s Same Planet, Different Effects and Bhai Raj Maharjan’s Powerlessness.

Fig. 4: Hope Amidst Despair, by SC Suman.

Another theme addressed in ‘Tangential Stress’ is the toll of psychological and social isolation. Batsa Gopal Vaidya’s Lockdown and Ranju Yadav’s Pregnancy During Pandemic each portray a singular figure – a masked boy and a pregnant woman, respectively – to evoke the peculiar combination of fear and loneliness characteristic of the COVID era. Gopal Kalapremi Shrestha’s series of two-tone, puzzle-like images reflects a pronounced disorientation through optical trickery, a chaos that reverberates with the psychological upheavals wrought by lockdowns. Kiran Manandhar’s The Eternal Debate yields a similar effect through its poignant portrayal of internal struggles and the conflicting facets of one’s self. Among the most effective paintings in this vein is Bidhata KC’s Ekkais Din – 21 Days. The mixed-media self-portrait represents the artist in quarantine after returning to Nepal from a residency in Vienna. Hers was a literal, spatial isolation as well as a psychological, emotional one. Her piece pays deliberate homage to Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss, yet with a clear difference: whereas Klimt’s famous painting shows two bodies entwined in embrace, KC’s self-portrait depicts only herself, looking somber. She is encircled by a ring of airplanes pointing in all directions, which surround a grid of scratchy designs and Nepali numerals, as if marking time on a prison wall.

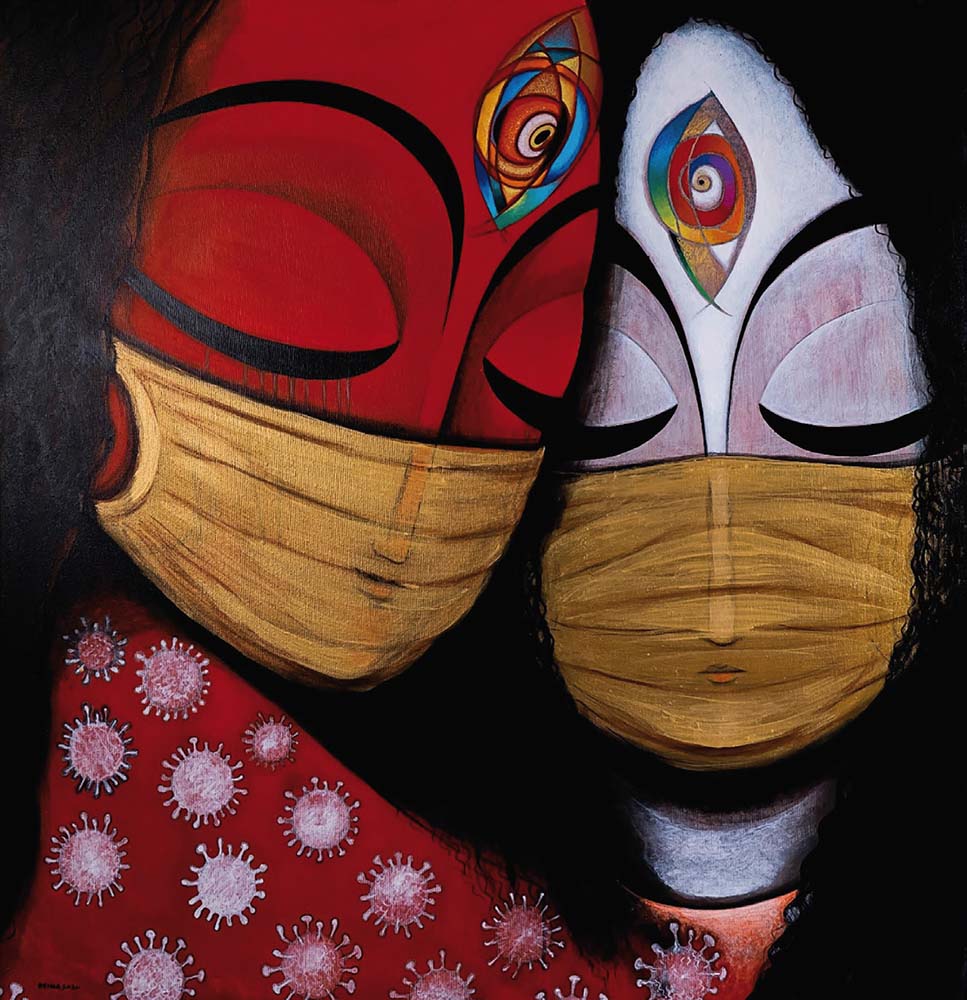

Destruction and hope

The exhibition is shot through with a central tension between destruction and hope. Rajani Sinkhwal’s Mahakala: Destruction with Cause shows the deity of destruction in detail; an apt symbol for a virus wreaking indiscriminate havoc across the world. In the face of such devastation, signs of hope, or at least consolation, can also be found: Pramila Bajracharya’s tribute to a healthcare worker in Your Life Before Mine, Manish Lal Shrestha’s ringing bell exploding with color in Sound of Silence, Erina Tamrakar’s masked figures tenderly posed in The Variable Gem. There is a certain solidarity during lockdown conditions, a recognition that humans are alone, but together. Govinda Lal Singh Dangol’s Daibya Shakti evokes this feeling by superimposing a globe upon a traditional Nepali door, a white facemask stretched across them both.

All these themes – destruction and solidarity, isolation and hope – stand out in SC Suman’s Hope Amidst Despair. The sharp composition foregrounds eight scenes of isolation. It looks as if the artist is capturing snapshot views through a series of windows, each one padlocked shut. Silhouettes – likely representing those lost to COVID – float through the marginal spaces between the frames, across a jumbled landscape of buildings and temples, world landmarks and staircases. The ‘outside’ is menacing, the ‘inside’ is stifling. An unassuming golden key hangs in the upper-right corner of the painting, hinting at the possibility of opening the padlocks that enforce our confinement, as if the solution to COVID were simple and just beyond reach.

Fig. 5: Ekkais Din – 21 Days, by Bidhata KC.

Considering how swiftly ‘Tangential Stress’ came together, it is admirable how well the commissioned works speak to one another. As a whole, they express the intersecting feelings that have come to characterise life during a global health crisis. Beyond the art’s aesthetic merits, the virtual nature of the exhibition amplifies the show’s themes: it is the pandemic itself that inhibits in-person appreciation of pandemic paintings. To take a remote, virtual tour constantly reminds viewers of the new reality addressed in the art. In that sense, ‘Tangential Stress’ is ideally suited to the present moment.

Fig. 6: The variable gem, by Erina Tamrakar.

Beyond this exhibition, the museum also launched a second virtual show entitled ‘Inception: A Collection of Nepali Masterpieces’ (https://www.360mona.com/inception), which highlights more traditional styles from Nepal. For those in Kathmandu, the MoNA is now open for public admission.

Benjamin Linder, currently a Fellow at IIAS, is an anthropologist focusing on socio-spatial transformations in urban Nepal. He previously worked with MoNA curator Rajan Sakya and others at the Kathmandu Guest House to produce the coffee-table book Thamel Through Time: Commemorating 50 Years of Kathmandu Guest House and Thamel 1968-2018.