Transcultural Objects from the Global Hispanophone

Transcultural objects are objects that have circulated beyond their place of origin, and, in that movement, acquired new meanings, adopted new uses, and transformed their destinations. Transculturation refers to the transformations that occur between cultures that come into contact with one another, resulting in the creation of new and unique cultural forms. The study of objects (material and non-material) as examples of transculturation is therefore an invitation to reflect on the creation, mobility, and alteration of things as they encounter other things, other places, and other people.

Art historians, historians, and anthropologists have largely seen the exchange of objects as part of human beings’ ways of learning, evolving, and relating to each other. Objects are therefore a source of knowledge. They speak and tell stories. What is more, in helping translate everyday practices from one place to another, they are agents of change and mediators of culture.

This Focus section explores the transcultural objects that have emerged from the contact among Spain, Latin America, Asia, and Africa. The essays gathered here are written by scholars in the fields of literary and cultural analysis, art history, and musicology. Their research on material culture extends our knowledge of the well-known transatlantic route that connected Spain with Latin American countries to lesser-known contact zones in the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, and the Pacific. The transcultural objects discussed in this Focus section reveal the historical and cultural links between places such as Mexico and Japan, Brazil and Africa, and the Philippines and Spain. The study of the cultural contact between Spanish-speaking countries and diasporic communities (and the field of study within which it falls) has recently been termed Studies of the Global Hispanophone.

Mindful of the colonial history that has brought these cultures into contact, the contributors to this issue revise, expand, and attempt to decolonize our knowledge of such encounters by introducing us to lesser-known histories through a series of objects that still exist today. We understand transcultural objects here in broad terms as encompassing not only material objects but also examples of transcultural legacies that take shape, for example, in architecture, food and cooking, lyric theatre, and even islands.

Overall this collection of essays emphasises (1) the processes of transculturation that brought such objects into being and (2) their transculturating power: in other words, what they do to the cultures they traverse. Transcultural objects are firmly grounded in particular geopolitical locations and have often been cast as commodities exchanged between static cultures. This collection stresses how such objects blur and connect the cultural formations through which they pass, mapping out new world geographies. Ultimately, we hope to offer alternative cartographies of the globe by tracing the lives of the transcultural objects presented here.

Ignacio López-Calvo introduces us to the afterlives of transpacific material culture through a number of objects that attest to early-modern, 20th-century, and contemporary Japanese-Mexican transculturation. The objects include foodstuffs (spice-covered peanuts, shaved flavoured ice, and the condiment known as chamoy); techniques for distilling tuba (Philippine coconut wine) and mezcal; items of clothing (China Poblana, the Mexican national dress); and ornamental plants such as Jacarandas. López-Calvo puts forward the idea that each object functions as a symbolic repository of memories and identities that are transmitted from generation to generation, both among the Japanese diaspora in Mexico and back “home” in Japan. Likewise, López-Calvo also alerts us to how certain objects and social practices lose emotional value with the passing of time.

In “Islands of the Global Hispanophone,” Benita Sampedro Vizcaya attends to islands as transcultural objects. Against visions of islands as picturesque tropical paradises, her lucid text proposes understanding historical islands as imperial spaces of exile, deterritorialisation, trade, enslavement, militarisation, and exploitation. Her claim that islands have often been the first (graspable, physical) object of conquest illuminates the colonial imagination, which Sampedro Vizcaya proposes should be assessed in tandem with the perspectives of island dwellers. In doing so, she emphasises the epistemological possibilities that arise from centring studies of colonial pasts and presents on the specificities of islands as well as their relationality with land and water. Her piece explores places such as Cuba, the Canary Islands, Annobón, and Fernando Poo (currently Bioko), which is situated off the West African coast.

Paula Park’s piece follows the trajectory of the Brazilian musical instrument known as the berimbau through its travels from Africa, presumably through the Philippines, to South America. In parallel with this, she also traces the itinerary of its counterpart, the belembaotuyan, played by Chamorro people in Guam. In admirable detail, Park explains the craft that goes into making these instruments. She also highlights their commonalities, which include the use of a gourd as the resonance box, the twangy sound they produce, and a possible link to an earlier string-bow instrument from Africa. Park also notes remarkable differences that arise when the berimbau and belembaotuyan are played in different locations or cultures. This piece tells a curious and truly global story about the belembaotuyan, which was presumably brought to the island of Guam by crews of the Manila galleons during way-stops in their journeys across the Pacific. Slaves, who were familiar with other versions of string-bow instruments from their homelands, started to play the belembaotuyan and make their own music. If nowadays the sound of the Brazilian berimbau is intrinsically linked to capoeira and Brazil, the research that Park has conducted on the belembaotuyan in Guam contributes to the study of material culture from what might be called the Latin Black Pacific.

From a different location, the Hispanic Philippines, Mario Quijano analyses the transculturation of a genre of lyrical theatre named sarswela, which became a popular form of entertainment at the turn of the 20th century. Quijano briefly traces the evolution of the genre from Spanish zarzuela. Having initially been written and performed in Spanish by Spaniards, it was later taken up by Filipinos (mostly) in Manila. Slowly, Filipino themes and genres (such as the love songs known as kundiman) were introduced into the performances. Philippine sarswela appeared in the context of an emerging nationalism fostered by artists and politicians. Its plays were written and performed in Tagalog and other Philippine languages; they were put on in Manila but also elsewhere in the archipelago. Anecdotally, Quijano comments on specific customs (such as issuing weather warnings and dispersing crowds of spectators who have not paid) that would often be considered part of how performances are managed. This piece is crucial for understanding the transculturating potential of art forms that, far from copying the (European) centre, represent symptoms of local creativity.

If theatres were built in the Philippines specifically for performances of sarswelas, the construction of churches was a symbol of Christian conquest and colonialism, but also of artistic transculturation. In his analysis of a sculptural relief on the Church of Saint Joaquin in IloIlo (Visayas), Patrick Flores demonstrates that the Spaniards spread their images and pictorial rhetoric across the colonial world. Here, the imagery of the Spanish Reconquest (a combination of war, violence, and baroque expressionism) was introduced to the Philippines. The relief commemorates the surrender of Tetouan, the Moroccan city whose defeat at the hands of the Spanish in the 17th century became so emblematic of imperial power that it was reproduced thousands of kilometres away in the Philippines. In addition to admiring the distinctiveness of Catholic churches in the Philippines, Flores’ text underscores the relevance of art and architecture as part of world art history.

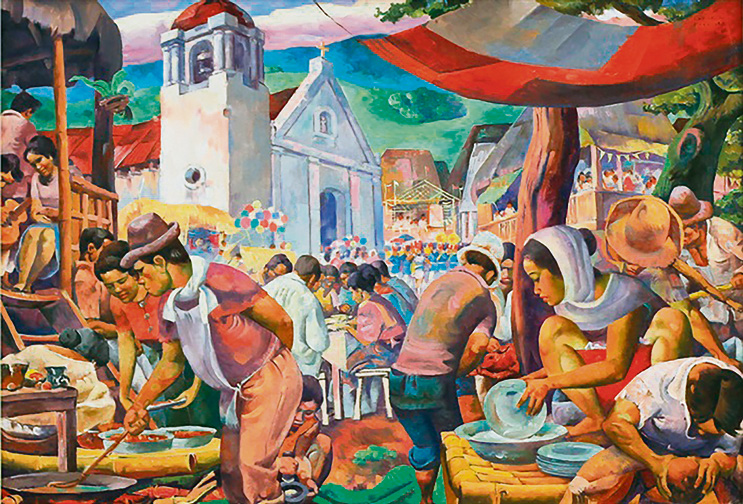

It is clear from this introduction that linguistic transculturation is part of the lives and afterlives of these objects, whose original names, new names, alternative spellings, and adaptations are as necessary as they are innovative. Linguistic transculturation is also evidence of the glocality of transcultural objects: their existence (and meaning) in a particular place and time is the result of global influences. Foreign words in local languages are best understood by the communities in which they are created, and therefore where they feel at home. Pista ng Angono (or The Fiesta of Angono), a painting by Filipino muralist Carlos “Botong” Francisco [Figure 2], is illustrative, in its title and in its representation, of a Philippine town fiesta, which is uniquely familiar to the Philippine cultural imaginary.

In addition to offering our readers the opportunity to learn about transcultural objects from the Global Hispanophone and to show how this method and field of inquiry helps us to gain planetary consciousness, we hope to spark our readers’ curiosity to know more about the lives of the things that surround us.

Irene Villaescusa Illán is an Assistant Professor of Cultural Analysis at the University of Amsterdam. Before moving to the Netherlands, she lived and worked in Hong Kong. Her research has mostly focused on Philippine literature written in Spanish. Email: i.villaescusaillan@uva.nl