A Tailor Street in Singapore’s Chinatown

Before the advent of ready-made clothing, most Chinese who lived in Singapore’s town area knew where to go to get their clothing tailor made: Kwong Hup Yeun Gai (Cantonese: 廣合源街), or Pagoda Street as it is officially known. This essay accounts for the rise and fall of a tailor street in Singapore's Chinatown at the intersection of global clothing trends, the dynamics of business enclave formation, and the everyday history of shops and shopkeeping between 1945 and the 1980s. Asia has a long tradition of tailoring, but the urban tailor shop in Eastern Asia manifestly indigenized a Western and gendered (masculine) form of handicraft-based business and mode of consumption. The name yangfu dian (洋服店), literally Western Clothing Shop, originated during the Meiji era in Japan. From around the 1880s, beginning in Japan and spreading to the colonial and semi-colonial port cities across East and Southeast Asia, putting on the Western suit became a mark of the Asian man’s modernity and his assumption of Western “civilized” norms.

As early as 1880, the Master Tailors’ Association 新加坡轩辕洋服商会 (Xinjiapo Xuanyuan Yangfu Shanghui) was founded in Singapore. It was also in this decade that the English-educated Asian elite began to appear in suits. But these early (Chinese and Indian) tailor shops – congregating on High Street and Coleman Street – mostly served the European residents of the port city.

The mass adoption of the tailor-made shirt and trousers for everyday wear, and the suit for more formal occasions, most likely began in the 1920s. The rubber boom of the 1920s, mass schooling for the Chinese, the advent of the three “Worlds” Amusement Parks, and the circulation of Hollywood and Hollywood-mimicking Shanghai-made films, meant that it became an urbane expectation for the average male resident to be seen in shirt and trousers on the streets, if not yet at their workplaces. In 1932, The Singapore Directory, written with the visitor from China in mind, contained this sartorial commentary: “[Chinese] men mostly dress themselves in western clothing. In business settings, they often wear short sleeved shirts and broad trousers (阔裤 kuoku), with no distinction between daily and ceremonial wear. There isn't the practice here of putting on the (Chinese) long gown and jacket (长衫马褂 changsha magua 1

Two early advertisements from the inter-war period show how the imagined consumer still had to be educated and cajoled into tailoring shirts and trousers for everyday wear. In 1926, to advertise for its opening at 117 North Bridge Road, a tailor noted, “Clothing is what brings orderliness to one’s body, and if one sincerely wished to appear orderly through one’s clothing, then measurements have to be precise, and the cut has to fit your body.” It was further shared that the shop had all kinds of fabrics, and “could make Chinese and Western clothes for commercial and educational occasions.” 2 By 1934, the norms had somewhat shifted. Another tailor at No. 127 Amoy Street could now proposition their product as a familial norm to be passed down the generations, as depicted in this image of a suit-clad father telling his son, “The New Year is arriving, let’s go to Hock Seng Chun to make a new set of clothing” [Fig. 1]. 3

Fig. 1: Advertisement for a tailor shop in Nanyang Siang Pau on 30 November 1934. (Image courtesy of the Singapore Press Holdings)

The same 1932 directory listed 87 Chinese tailoring shops in the Singapore town area. The majority clustered along North Bridge Road (29), Selegie Road (20), and Coleman Street (9). Those on Coleman Street, along with their peers on High Street (1) and Tanglin Road (5), served mainly the European, Eurasian, and wealthy Asian clientele. The rest of the tailors catered to what was gradually becoming a daily necessity for the male half of the emerging Asian middle class. In the 1930s, there was little indication – beyond the three tailors which had set up shop there (Seng Chang 成昌, Nam Chang 南昌, and Hwa Hing 华興) – that Pagoda Street would later on develop into Singapore’s premier tailoring street.

Kwong Hup Yeun Gai(广合源街): From Vice to Tailoring Street

In fact, for most of its history, Pagoda Street had a seamy reputation for housing the town’s public brothels, coolie and opium dens, and setting the scene for Chinatown’s vice-related crimes. The street apparently acquired its colloquial Chinese name, “Kwong Hup Yeun,” from a 19th-century coolie-importing firm, whose history remains shrouded in myth. By the early 20th century, an area called Ngau Chey Sui (牛车水 Niu Che Shui) in Cantonese had appeared, with the opera houses, brothels, opium dens, and teahouses of Smith Street (戏院街Xiyuan Jie) at its centre. The area spilled from there into neighbouring streets (such as Pagoda Street and Keong Saik Road), but it was contained within the boundaries set by Neil Road, South Bridge Road, Tanjong Pagar, and Upper Cross Street. Ngau Chey Sui was an unapologetically Cantonese entertainment town. Before the Shanghainese turned up with their amusement parks and cinemas in the 1920s, the dandies of Singapore had to learn to swagger in Cantonese.

The first tailor shops on Kwong Hup Yeun Gai had to contend with this lively entertainment scene unfolding nightly on their shopfronts. They must have been attracted to the foot-traffic that accompanied the bustle of Chinatown. At the same time, the declining entertainment businesses, now increasingly seen as fuel for “vices” by reformists, created relatively cheaper rental opportunities. A quick search of Chinese news articles that mention the street from the 1920s reveal a spate of crimes ranging from petty theft to crimes of passion and murder.

The rapid expansion of the tailoring industry after the Second World War was a Singapore-wide phenomenon. From 87 shops in 1932, the number of Chinese-operated tailoring establishments grew to 394 by 1958, according to a commercial directory published in that year. North Bridge Road (40) and Selegie (20) continued to have the greatest concentrations of tailoring shops – close to one in every ten and one in every 20 were located there, respectively. More significant perhaps was the spread of tailoring services to suburban residential areas outside the town area: Geylang (27), Jalan Besar (16), Joo Chiat (15), and Serangoon Road (9).

While tailoring remained Cantonese-dominant in the town area, in Singapore’s suburbs, Hakkas – and later on Hainanese – began to make serious inroads. At its peak in the 1950s and 1960s, according to an estimate based on guild membership numbers, there might have been upwards of 1000 tailoring establishments across the island. By the late 1990s, there were perhaps no more than 200 tailoring shops still in operation. 4

The sudden expansion of tailoring after the war and its rapid decline after the mid-1970s can be traced to global structural causes. The story of Singapore’s rapid economic development since the 1950s – and the attendant growth of general demand for clothing – need not be repeated here. Likewise, the replacement of tailor-made clothing by mass-produced garments, marketed by global brands and made available in Singapore department stores from the 1970s and 1980s, is another well told tale.

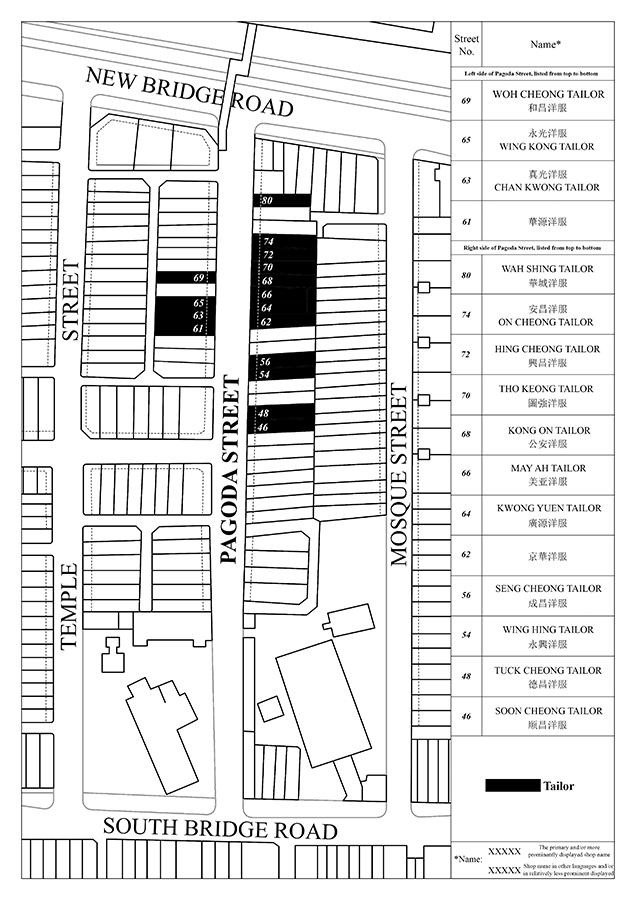

Kwong Hup Yeun Gai in Chinatown deserves a closer scrutiny as a tailoring street and community, which both rode on the crest of 1950s expansionism and somehow managed to buck the trend of rapid decline, at least up to the 1980s. In 1958, the street counted 13 tailoring concerns. This appears to be a smaller number compared to the other roads named above, but it was also the shortest street (perhaps one-fifth the length of North Bridge Road), thus making it probably the most densely packed area with tailors at that time. At its peak, perhaps in the 1970s, 23 out of 59 shops on the street were tailoring joints [Fig. 2]. A survey by a conservation advocacy group in 1985 showed that there were still 16 tailor shops operating on the street [Fig. 3]. Even on the eve of their collective closure, although the industry had declined, it was reportedly still the go-to place for tailor-made suits Chinese in Singapore. 5

Fig. 3: Map indicating tailor shops on Pagoda Street in 1985.

“(Even) customers from outside Niu Che Shui spoke Cantonese”

In accounting for the concentration of Cantonese tailors on Pagoda Street, the veteran tailor Wong Chew Chung (b. 1931) noted that even customers from outside Chinatown spoke Cantonese to the tailors 6 To the immigrant tailors, Pagoda Street offered the freedom of socializing freely in the language and culture of their home county. Language mattered. According to Wong, everywhere else, Cantonese and Hakka tailors learned to speak the language of their clientele: English in Katong and Tanglin, Malay in Geylang. Only on Kwong Hup Yeu Gai did Chinese customers of all dialect backgrounds conform to the lingua franca of Ngau Chey Sui. 7

It is easy to forget today that Ngau Chey Sui was still a “Chinatown” in the 1950s, in the sense that the majority of its residents were first-generation newcomers. In 1948, when Wong Chew Chung arrived in Singapore as a 17-year-old migrant, he already had one foot in the door of the tailoring industry. His father had been in Singapore, most likely from before WWII, and was working as a tailor in a shop on North Bridge Road. Chew Chung and his father were cramped into a second-floor room on 55 Sago Street with four other Cantonese migrant workers: three tailors and two other workers. It was his fathers’ friends who helped placed him as an apprentice in the tailor shop Chan Kwong Kongsi (真光公司 Zhenguang Gongsi) at 63 Pagoda Street.

At Chan Kwong, Chew Chung learned his craft from the bottom up, lived on the premises of the shop, and went unpaid for two years (1950-2). Upon completion of the apprenticeship, he was offered a job as a tailor in the shop for the salary of $120 (Malayan dollars) a month. Determined to be his own boss, he quit after two months to start his own business in Kim Chuan Road (Paya Lebar). He then moved to Geylang before finally settling in Katong (Shopping Centre) in the 1990s.

Although his familial network landed him a job, there was no way for a newcomer like Chew Chung to set up shop in a premier retailing location like Kwong Hup Yeun Gai. Due to rent control legislation, rent was low ($80 a month in the 1950s), so that the market value of the retail space came to be expressed in the form of an unofficial “entry fee” called “kopi-money.” Chew Chung’s boss, the towkay of Chan Kwong Kongsi, could only afford the $6000 “kopi-money” to lease the shop in 1948 thanks to help from a brother-in-law, who was running a textile-related business on Arab Street. The entry fee was the equivalent of 50 months of the confirmed tailor’s salary. 8

As business on the street boomed during the 1950s, it was the already established insiders who muscled in on whatever limited shopfront retail space came on the market. Chan Pak Heong (陈伯雄 Chen Boxiong), a second-generation owner of Seng Cheong Tailoring Shop (成昌洋服Chengchang Yangfu), the oldest on the block (since 1918) at no. 46 and 48, co-owned two shops with his brother, and subsequently invested in at least a few others on the street through his relatives. At least four shops on the streets were co-owned by two other pairs of fraternal brothers. In other words, a random customer on Pagoda Street had a one-in-four chance of walking into a Chan family-owned shop. By the 1960s, the unofficial entry fee for leasing a shop on Pagoda Street had risen to between $10,000 and $20,000. (Malayan dollars)

The tailoring shop was a craft-based family business. The towkay was hence at once the master craftsman, the business owner, and the family patriarch. The shops on Pagoda Street were considered “big” by contemporary industry standards. Each firm had on average 20 members, including the towkay, his wife, 15 or so tailors, and two or three apprentices. A “medium”-sized shop would be run by the towkay and his wife, along with family members and two to four hired assistants. 9 The tailoring shop was equipped such that every worker would have his own sewing machine – 20 for the big tailor shops, and five to ten for the medium-sized tailor shops. The shop came together as a “family” through the meals that were provided for all employees. Everyone sat together and ate the same two meals provided by the towkay: an early lunch at 9:30 A.M. before the shop opened and a dinner before the busiest retailing hours of the day (i.e., the final two hours before the shop closed at 9:00 P.M.). Everyone worked seven days a week, with only four days off during the Lunar New Year celebrations.

Physically the shop was broken up into three parts on the ground floor. The retailing space on the shopfront was about ten metres deep. In addition to the huge tailoring tables, a big shop would display upwards of 50 types of fabrics in their glass cabinets, which customers could touch and feel on request. The towkay-cum-master-tailor helmed the shopfront, and he played the role of making the sales pitch, measuring, fitting, and most important of all, cutting (裁剪 caijian) the fabric. The back end, filled with 20 sewing machines, served as the workshop, where workers spent the long workday producing as many as five shirts per person per day. Separating the two spaces, interestingly, was the kitchen, which was helmed either by the towkay’s wife or a hired cook.

Tailor shops on Pagoda Street predominantly served the local Chinese market. Plain short-sleeved shirts and trousers would have been the most in demand by men in business for everyday wear. Another staple was shorts worn by working-class men. The very first item an apprentice was made to learn to sew was a set of shorts that would subsequently become his attire in the shop. The most challenging to assemble item was the suit. For businessmen of some standing, who had to regularly attend social functions in the guilds or huiguans, it had become an expectation since the 1920s to put on the suit. Although not as much in demand, tailors could also make the formal suit for black-tie events. As Wong Chew Chung put it, the suit is “easy to make, but whether it’s beautiful and fitting, that's another question.” 10

Heritage Businesses in Singapore

The decline of tailoring in Singapore, and on Pagoda Street in particular, in the face of the industrial manufacturing of ready-made clothing since the 1970s and 1980s was perhaps inevitable. To many of the towkays, the business was a means of supporting their families. The uncertainty of the business meant that from the 1980s onwards, it became harder for families to pass them to children, who tended to be better educated and had more attractive career options. Many of the towkays simply chose to end their businesses in 1993, when their shops were acquired by the government for urban renewal.

Fig. 4: Interior of Tuck Cheong Tailor preserved and on display in the Chinatown Heritage Centre. (Photo by the author, 2025)

In recent years, the National Heritage Board in Singapore has begun to champion the cause of heritage businesses – small businesses that have been passed down for three or more generations. On Pagoda Street, however, all of the tailor shops of yesteryear are gone. One of them, Tuck Cheong Tailor, however, has its furniture and interior décor preserved and displayed by the Singapore Tourism Board in the Chinatown Heritage Centre [Fig. 4]. While that is to be lauded, it is a pity that all the tailoring shops were closed en masse during the 1990s. Had one or two shops been allowed to carry on, it is plausible, especially from today’s perspective, that an institution like the fashion department of an arts college might “adopt” the space as a both a practicing heritage site, and a design studio for older tailors and young designers to meet and interact. 11

Seng Guo-Quan is Assistant Professor in the Department of History at the National University of Singapore. Email: hissgq@nus.edu.sg