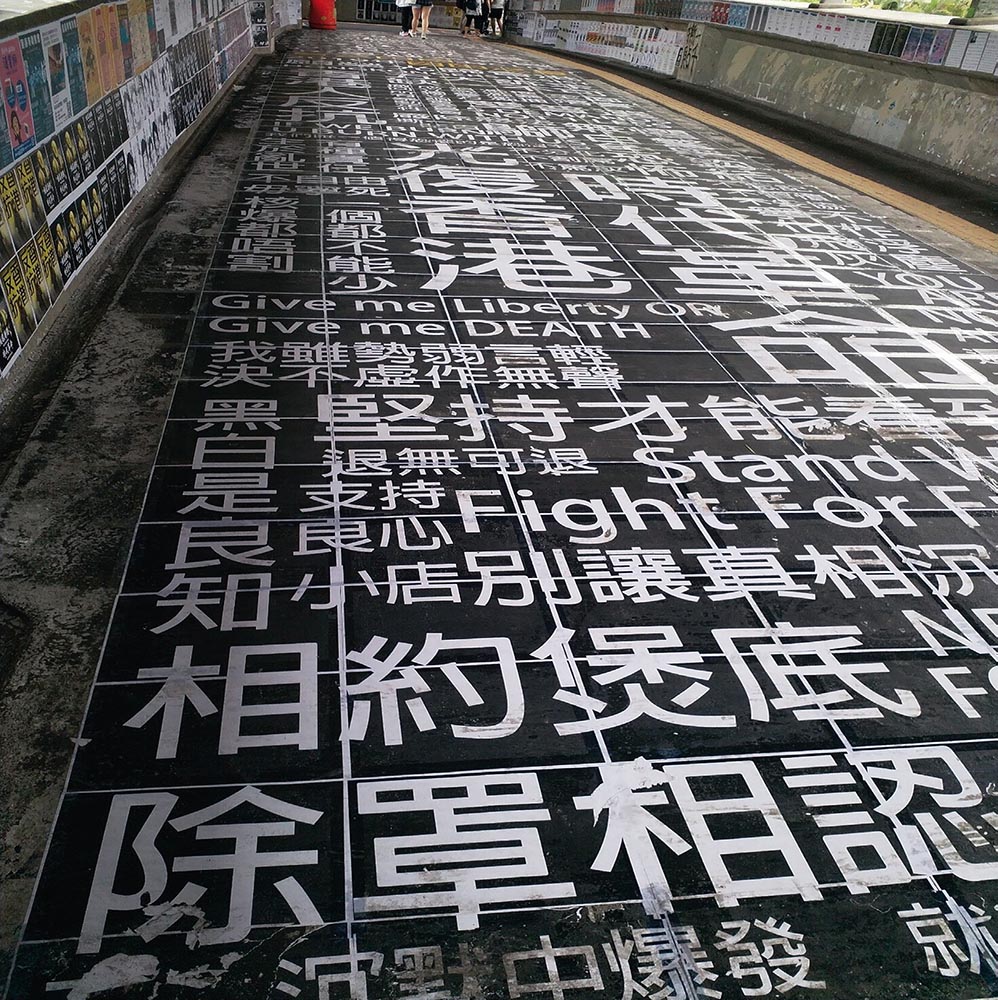

Surrounded by slogans. Perpetual protest in public space during the Hong Kong 2019 protests

On the way to the metro, I walk past graffiti and posters asking me to be conscious and supportive of the protests. In the metro itself footage of protesters is shown on the many television screens.1 Public space in Hong Kong can no longer be neutral, it seems. The protests in Hong Kong are entering their fifth month at the time of writing. Originally demanding the withdrawal of a controversial extradition bill, they quickly transformed into a larger cry for accountability of those in power, with universal suffrage and an independent investigation into police brutality amongst the five main demands. The Lennon Walls2 that have popped up all over Hong Kong and other places across the world are home to post-its, posters and various other visual media, put there by anyone wishing to express their support for the movement. In this article I discuss the transformation of Hong Kong’s public areas into spaces of perpetual protest.

Fig. 1: The ‘Lennon Bridge’ in Tai Wo Hau.

It is nearly impossible to walk anywhere in Hong Kong today without encountering signs and slogans of the protests on walls, pavements, railings, walkways, poles, ceilings and so on. Furthermore, buildings targeted for their (perceived) support of the Communist Party have fortified themselves with bars and reinforced doors, adding to the changing image of Hong Kong’s streets.

One of the most impressive aspects of the movement is its diversity and expertise in visual imagery. The use of social media and image hosting sites, combined with Hong Kong’s population density and high economic development, allows for a rapid spread and high visibility of new protest images. Some of these are curated, organized by certain organizations, but others are more guerrilla in nature, posted online for anyone to print out and disperse across Hong Kong. Based on a number of photos taken during the movement I discuss some themes and motives that characterize the visual makeup of the protests, along the lines of four categories: ‘memory and remembrance’, ‘appeals and explanation’, ‘beyond the local context’, and ‘the changing city’.

Memory and remembrance

The movement uses dates as stark reminders of events in the past. Repeated references to these dates help to legitimise the movement by giving it a solid foundation of historic events. The dates are displayed on so-called ‘protest calendars’ (fig.2), and considering the censorship regime of the ever-encroaching mainland China, it makes perfect sense to connect to and remind people of its history.

Fig. 2: Remembering the movement near Wong Tai Sin temple.

Memories of important protest events are kept alive through posters displaying, and chants repeating, their dates. For example, references to ‘6.4’ (六四 ), the date of the Tiananmen massacre, are a relatively common sight (see fig.3).

Fig. 3: Appeals to history and memory at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

‘7.21’ and ‘8.31’ are two other well-known dates; the first refers to the attacks on protesters by assailants with knives on 21 July 2019, and the second to the police violence inside a metro station on 31 August 2019. Other dates such as ‘10.1’ and ‘8.11’ again refer to incidents of police violence: respectively, the first live gunshot injury and a rubber bullet shot into a protester’s eye (see fig.4). Dates have become part of the canon of Hong Kong protests, with numerous public displays urging us to remember. This is also typified in graffiti seen around the city stating, “Some moved on, but not us”, or “we will never forget”. Slogans such as 毋忘721 831 [Don’t forget 721 831!] are seen all over Hong Kong.

Historical appeals are powerful metaphors. There is an awareness among the protesters of China’s power of their need to shape the narrative. The ubiquitous nature of these ‘calendars’ shows a protest against a regime that has a tight grip on the memory and history of its people. They appeal to their observers to remember and spread the word, and not fall prey to manipulation and subversion by the Chinese state. Some posters, written in simplified Chinese, directly appeal to the many mainland Chinese visitors with the aim to unbalance the state’s narrative. These posters are engaged in a silent battle with the state’s propaganda apparatus.

Appeals and explanation

A second major part of the visual makeup of the movement is clarification. Acts of vandalism or destruction are explained by protestors – on site – to inform passers-by, with the intention to spread a message that goes beyond wanton violence. Figure 4 shows a vandalized Starbucks, targeted by protestors because the branch is managed by the pro-Beijing Maxim’s Group. The spray-painted texts explain their reasons as well as their vow to not steal from the property.

Fig. 4: Informing the public about vandalism; photo taken near Jordan.

The promise and act of not stealing is vital as it crystalizes the vandalism as ideological destruction. The belief in this ethos was exemplified by a person being tied up and left for the police after he was seen trying to loot a XiaoMi store.3 Other public messages explain why the MTR is a target of attacks, or why certain stores are boycotted, or as the movement grew more violent, became a target for ‘renovations’. The MTR was targeted due to its perceived role in assisting the police as well as possibly ‘covering up’ police brutality by refusing to make camera footage inside the stations public. Most famously on 31 August (8.31.), when policemen entered the station and clashes took place. Rumours of possible deaths due to police brutality spread rapidly leading to outrage and further demands of public accountability of the police and the possible role of the MTR in protecting or facilitating the authorities.

Beyond the local context: from offline to online, domestic to abroad

A large part of the movement is its digital sensibility. This bleeds into the real world as online memes and imageries are reproduced on the streets. Technologies such as QR codes serve to establish an ephemeral bridge between the ‘real’ world and the digital world ‘out there’, reached through our phones on the streets. Pepe the Frog, an American cartoon character, has been adopted by the protesters as an icon (fig.5).

Fig. 5: Online and offline in Diamond Hill.

Other cartoon characters, such as the dog (連狗) and pig (連豬) (fig.6), hail from the LIHKG Forum, one of Hong Kong’s most popular forums and used by many protesters. The protesters have been identified as “young, educated, and middle class”,4 which explains the popularity of using emblematic icons taken from the internet. These images can digitally communicate the protest message beyond the local context, across the world, shared through social media.

Fig. 6: Emojis come to life at University Station 黨鐡不了 [Cannot stand the (communist) party rail].

With ‘beyond the local context’ I refer to the strategy of sharing that underlies the protests. Clearly, posters and other visuals are made not exclusively for the local observer but with (international) television and social media in mind. Exemplary of this strategy are protest messages at university graduation ceremonies. By cladding the walls of graduation venues with protest images and slogans, most photos taken at the ceremony will become carriers of pro-protest messages. As people share their pictures of Hong Kong, they inadvertently share protest messages.

The changing city: accommodating the protests

The visual media in the public space ensures one is constantly reminded of the protests during the daily commute. Recently, however, the reminders are also found in the structural changes that the city has been submitted to. The city is bearing silent witness to the breakdown of the normal state of being. The changing cityscape is reacting to and accommodating the protests in different ways. For example, in anticipation of large crowds and for safety concerns, fences and chains at pedestrian crossings have been removed and replaced with simple tape. The little changes affect the way in which we now navigate the city. Metal grating was installed to open sides of railway bridges/walkways after the protests started, most likely to prevent people (protesters) from throwing things onto the rails, or accessing the station after closing time (fig.7).

Fig. 7: Newly installed grates near above Kowloon Tong metro station.

Lastly are some of the protective measures taken by many companies, such as the Bank of China, Yoshinoya and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. Due to the recent targeting of ‘pro-Beijing’ establishments, some companies have opted to protect their properties; glass windows have, for example, made way for metal panels, further changing the atmosphere on the streets (fig.8). Walking around Hong Kong, some establishments look like construction sites blending into the background, with only simple signs fixed to the facade betraying their function.

Fig. 8: San Po Kong Bank of China ‘bunker’, showing security measures taken.

Keeping the movement alive

Everyday space has become protest space, but the protest has also bled into the fabric of everyday life. Many restaurants have televisions broadcasting the news; the Metro, used by a majority of the population, shows protest footage inside the train cars, making it near impossible to escape the protests even on quiet days. Not to mention the categorization of restaurants and businesses into ‘Yellow’ (pro-protesters) or ‘Blue’ (pro-police). The political becomes the everyday.

The protesters have succeeded brilliantly in transforming Hong Kong into a political site. I have shown but a snapshot of the diversity of the visual culture of the movement and have left out many of the common slogans sprayed all over Hong Kong, such as 光复香港,时代革命 [Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times],香港人加油 [Keep it up Hong Kongers], which later turned into 香港反抗 [Hong Konger – resist], a more provocative statement. Revising this article several months later, the slogan 香港人報仇 [Hong Kongers take revenge] has become popular, as the general legitimacy of the government and police force continues to be eroded.

Travelling anywhere within Hong Kong one is sure to encounter some form of protest related art, be it graffiti, posters or some other method of altering the public space. The protestors have also cleverly managed to dance between off- and online space, national and international space. International attention is seen as an effective weapon to put pressure on the government and many of the posters speak beyond the observer on the ground. There is a digital strategy of sharing, spreading, and making viral the protest’s art. It is a constant game between the government who regularly cleans up contested sites, and protesters who come back the next day with updated posters, occasionally even sardonically thanking the government for cleaning up the old, irrelevant posters and giving them a blank canvas to express themselves.

A final point relating to digital technologies is the blurring of audience of these images. Many images are meant to be photographed and shared, rather than seen by passers-by. One example are the many posters that speak directly to foreign leaders, imploring them to intervene. Or the posters thanking other countries for showing solidarity with the Hong Kong movement. These speak ‘beyond’ the local, relying on the press and local observers to share these online. They are decontextualized within Hong Kong in order to speak beyond.

The ever-developing professionalization and standardization of the protest art is also of note. Different forms are being explored, such as the post-it imagery of the dog and pig. Other locations might feature large art pieces tailor-made to fit a precise location, such as on the ‘Lennon bridge’ (fig. 1). The movement is more than people semi-randomly sticking flyers on walls; it is seemingly blossoming in its creative expression, and speed of employment. By turning everyday space into protest space the protests, since June, have turned Hong Kong into a space of perpetual protest reaching beyond the local into the digital world and through it, the entire physical world.

Postscript

Revising this article several months later with still no end in sight, most of the artwork has been removed or replaced by more recent versions (fig. 9). The government has stepped up its efforts to clean up the city, leading to new strategies and tactics in a city engulfed in a seemingly endless daily struggle.

Fig. 9: Graffiti has been painted over.

Milan Ismangil, PhD candidate at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, writes about culture and everyday life https://notjustaboutculture.com