Surprising Testimonies: Retracing the Trajectories of Highland Minority Refugee-Soldiers under the Khmer Republic

The difficulty of finding official written records on the Khmer Republic appeared to me unexpectedly, during ethnographic fieldwork in the hilly province of Mondulkiri. I had set out to study how indigenous Bunong highland dwellers made sense of Christianity. I learned that many had converted in the early 1970s, after having crossed the nearby border to South Vietnam, fleeing American bombings and Khmer Rouge rebels. However, I also heard that some of these refugees were repatriated to Cambodia to become soldiers. Hence, I found myself in search of written proof of this recruitment and of the underlying military relations between Cambodia and South Vietnam.

In May 2009 I first met Mé Nok and Pö Nok at their home with my Bunong colleague Neth Prak. 1 We had gone to see the elderly couple because wife and husband were first-generation Protestants. I had heard many stories of escape, but what Mé Nok and Pö Nok told us surprised me to the point that I initially thought that I must have misunderstood something. After their escape to a refugee camp in South Vietnam, they said, they converted to Christianity in Phnom Penh. Neither Neth nor I had heard of Bunong people living in the capital at that time.

We learned that Pö Nok had been recruited in the Bu Bong refugee camp by a highly placed Bunong military official who told him that he would be taken back to Cambodia to help defend his homelands. He and Mé Nok said that they boarded a helicopter along with hundreds of fellow Bunong refugees. After a training near Saigon, the recruits were brought to Phnom Penh and settled in a camp on Chroy Changvar, a peninsula that separates the Tonle Sap and Mekong rivers, directly across from the royal palace. Rather than being sent to fight in their native Mondulkiri, many of the Bunong soldiers were asked to guard bridges that linked the city to the surrounding province.

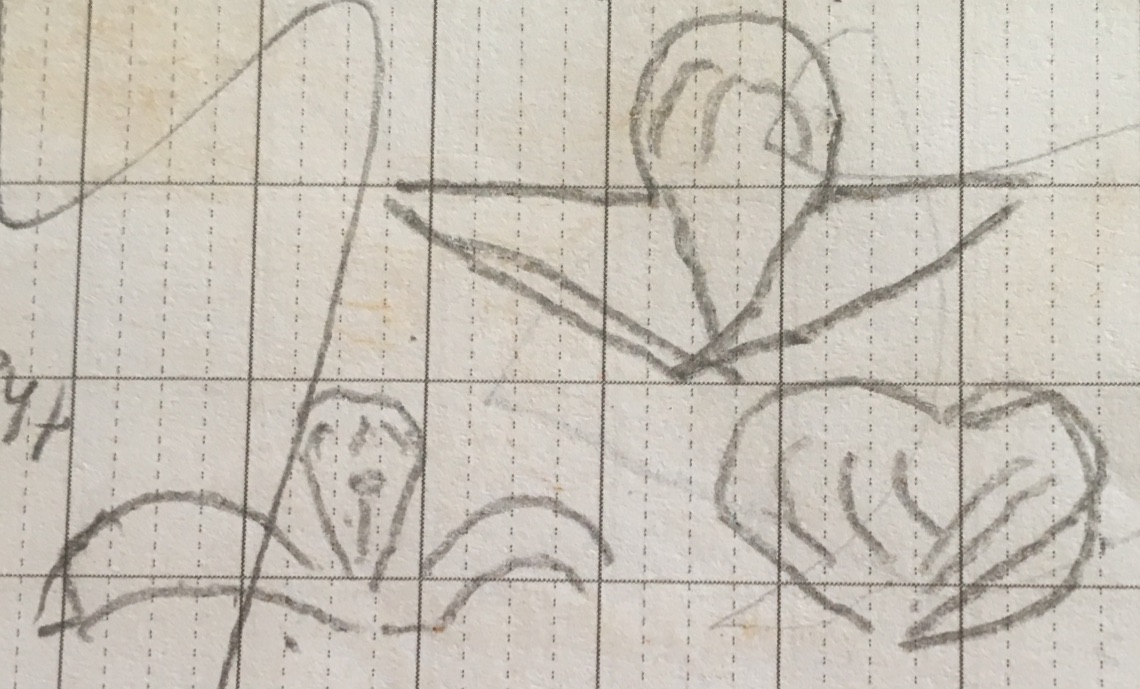

Fig. 2: Sketch of the three insignia. (Drawing by Pö Mon, 2020; Photo courtesy of Catherine Scheer)

On 17 April 1975, those Bunong who had survived to that point were killed by the Khmer Rouge, seemingly with few exceptions. Mé Nok and Pö Nok told us about one other survivor, Pö Mon, who had similarly been recruited in the South Vietnamese refugee camp and joined the Cambodian Special Forces. I found no sign of other survivors, only Bunong people who told me about family members who had left the camp for Phnom Penh and never came back.

Unfortunately, I did not have the chance to explore this historic episode further during my PhD research, but I got back to it as soon as I could. With only three elderly witnesses, it was urgent. Their accounts enabled me to retrace the Bunong refugees’ trajectories and learn about their life in Phnom Penh, but they did not provide much information about the political backdrop.

Two secondary sources provided clues. One is Po Dharma’s 2006 history of the Front Uni de Lutte des Races Opprimées (FULRO), an ethno-nationalist movement that connected South Vietnamese highland minorities to Cambodia-based Cham and Khmer Krom who also resented the Vietnamese power. Po Dharma mentioned the creation of a special brigade within the Khmer Republic’s army that was to put FULRO militants under the command of Colonel Les Kosem, the movement’s Cham leader. The names of two of the original highland commanders matched those given by Mé Nok as the leaders of the camp in Chroy Changvar. Thus, a link to the FULRO was established.

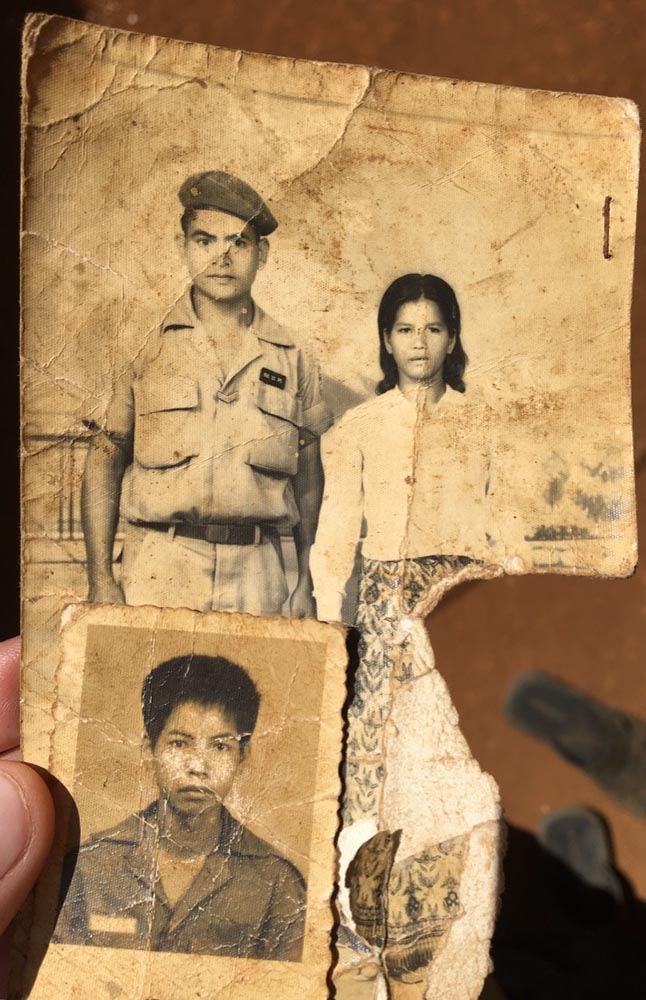

Fig. 3: Interview with Bunong sisters showing the picture of their lost siblings and brother-in-law. (Photo courtesy of Kim Sochea, 2020)

This link was corroborated in 2017 by William Chickering, a former “Green Beret” in the United States Army, who was stationed in South Vietnam in the 1960s, worked as a journalist in Phnom Penh in the early 1970s, and has written a history of the FULRO. 2 Chickering knew the highland leaders of the movement and confirmed to me that they oversaw the Bunong soldiers in Phnom Penh.

The other useful secondary source is Gerald Hickey’s 1982 ethno-history of the war years in the central highlands of Vietnam, which mentions in passing that in 1970, FULRO leaders, who came from the highlands of Vietnam and were based in Phnom Penh, “made frequent visits to Vietnam to recruit highlanders to go to Cambodia.” 3 His 1970 note on the “The War in Cambodia” for the Rand Corporation details Les Kosem’s plan to create a highland armed force intended to operate as a guerrilla group in the mountainous border regions between Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. 4

The first written report that I came across confirming that Bunong refugees, in particular, had enlisted in the Khmer Republic’s army was a brief 1971 Le Monde article by Jean-Claude Pomonti. 5

Fig. 4: The original photos of the lost family members taken in the early 1970s and their recent photo-edited reunion. (Photo courtesy of the Breen sisters [Yeut, Reut, and Weut], 2020)

The only official documents recording these highlanders’ transfer from South Vietnam to Cambodia that I have found are among the over 2000 eclectic documents in the Les Kosem archives, which have been available for consultation at the Documentation Center of Cambodia since 2022. There, I discovered three edifying letters, all from June and July 1971.

In one, the Prime Minister of the Republic of Vietnam [RVN] agrees to a May 1971 request by Khmer Republic Premier Lon Nol to allow “the recruitment of 1600 men among the active elements of the Khmer refugees from Mondulkiri in Quang Duc.” 6 In another, the RVN Ministry of Defense writes to the representative of the Khmer Republic’s army about recruitment and training support that the RVN was providing. 7 Finally, there was a correspondence between the Khmer Republic’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and its Ambassador to RVN that inventories the “Khmer Loeu” (“Upland Khmer”) 8 in the Bu Bong camp, many of whom wanted to be “repatriated” to Cambodia.

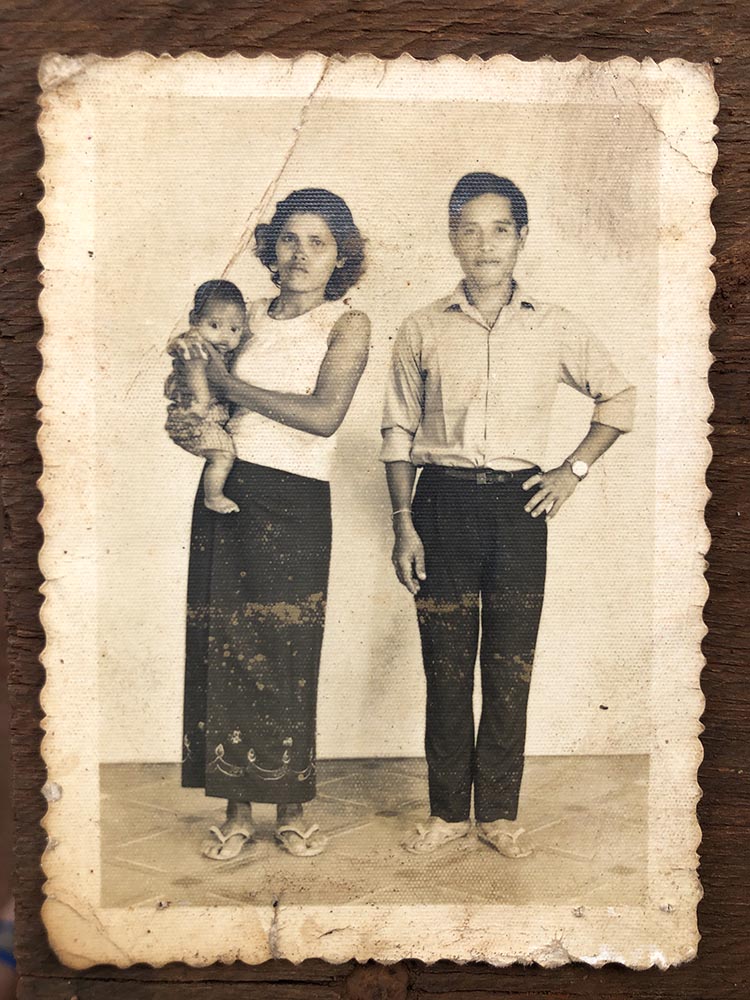

Fig. 5 : The 1970s originals showing the Bunong men in their Khmer National Armed Forces uniform. (Photo courtesy of the Breen sisters [Yeut, Reut, and Weut], 2020)

To check whether the Vietnamese archives held more evidence of this collaboration, I asked the help of Huy Bảo Nguyễn Phúc, a Vietnamese history student. Despite an extensive search through files held in Ho Chi Minh City, he did not find anything about the “Khmer Loeu” refugees’ transfer to Phnom Penh.

In addition to cross-checking how my three witnesses came to Phnom Penh, specific aspects of their journey necessitated further inquiry. Some led me to delve into military history. Kenneth Conboy, an American policy analyst interested in Southeast Asian armed forces, published several books containing illustrations of insignia. In 2019, during one of my last long conversations with Pö Mon, I asked him whether he remembered the insignia on his Cambodian Special Forces uniform. Without much hesitation, he drew three parachute insignias in my notebook: a Khmer, a Thai, and a U.S. one, closely resembling those depicted in Conboy’s work [Figs. 1 and 2].

Fig. 6: Mé and Pö Nok retrieved the photo after their return to the highlands in the 1990s. They had survived the Khmer Rouge regime and made it back all the way up to Mondulkiri. There, they reunited with Mé Nok’s sister, who had been repatriated from Vietnam in 1986 and kept the photo safe all those years. (Photo courtesy of Mé and Pö Nok, 2022)

Photos also unexpectedly appeared in the field. In Mondulkiri in 2020 we were interviewing three sisters, who had stayed behind in the refugee camp in Vietnam while two of their siblings left for Cambodia [Fig. 3]. A large, plasticized color photo featured their long-lost sister, next to her husband and her younger brother, both in uniform [Fig. 4]. They also showed me the two timeworn black-and-white photos taken in Phnom Penh on which the colorized version was based [Fig. 5].

The sisters explained that the Bunong recruiter who travelled back and forth between Phnom Penh and the South Vietnamese camps carried news and photos between separated family members.

Another of these rare visual testimonies turned up in 2022, when Mé Nok and Pö Nok’s daughter showed me a colorized photo of her parents with a baby [Fig. 6]. Tucked into the back of the frame was the faded and creased black-and-white photo. It had been taken in Phnom Penh and carried back to Mé Nok’s parents and younger sister, who had stayed behind in Vietnam.

The testimonies of Pö Mon, Mé and Pö Nok, and others have shone some light into a dark corner of history. Further research in the Vietnamese archives might provide a better understanding of the decisions that shaped the highland minorities’ trajectories. But now it is urgent to talk to elderly Bunong and other highland holders of oral history. Their testimonies fill in some of the numerous gaps in a dominant history that has largely shut them out.

Catherine Scheer is assistant professor in anthropology at the French School of Asian Studies (EFEO) and statutory researcher at the Centre for Southeast Asia (CASE). Her research involves highland dwellers in Cambodia’s margins and questions their recent history as well as the intersection of Christian missions, development work, and indigenous rights activism. Email: catherine.scheer@efeo.net