Silk Road Treasures on Show at a New Exhibition at the Louvre Museum in Paris

“The Splendours of Uzbekistan’s Oases” opened on 23 November 2022 and will run until 6 March 2023. It is the first Louvre exhibition to feature more than 170 artefacts from the Silk Road urban centres situated on the territory of present-day Uzbekistan.

The title of the exhibition entices the viewer to believe that the history of the vast region, narrated from the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE until the powerful Timurid empire from the early 15th century, is closely related to the history of the contemporary nation-state of Uzbekistan. The truth is that the first Uzbek ethnic tribes settled in Transoxiana, the territory between the Oxus (Amu Darya) and the Jaxartes (Sur Darya) rivers, at the beginning of the 16th century. The Buddhist, Zoroastrian, and Islamic artefacts on show were created long before the borders of present-day Uzbekistan were delimitated by Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union in the early 1920s. In an attempt to attract international investors and to boost the tourist potential of the post-Soviet independent state of Uzbekistan, the exhibition serves a rather politically connotated agenda. The show is co-organized by the Louvre in partnership with the Art and Culture Development Foundation of the Republic of Uzbekistan established under the Cabinet of Ministers. The French President Emmanuel Macron and the Uzbek President Shavkat Mirzoyev attended the officially opening on 22 November 2022 in Paris.

The exhibition took more than five years to organize. Initially planned in the larger Hall Napoléon, the current show had to adjust to the newly allocated and much smaller enfilade gallery of the Richelieu Wing on the first underground floor of the Louvre [Fig.1]. Due to the lack of space, the star piece – the southern wall of the Sogdian Hall of the Ambassadors from the mid-7th century [Fig. 2] is exhibited in the Islamic Galleries which disrupts the logical flow of this important exhibition.

Fig. 1: Entrance to the exhibition, Louvre, Paris. Photograph by the author, 2022.

In order to fully grasp the significance of the event, the viewers are repeatedly told by means of short texts illustrating each historic period that the artefacts they see leave Uzbekistan for the first time. Indeed, the span of the exhibition, chronologically covering more than 1,900 years of the most sophisticated cultural production along the Silk Roads, is truly breath-taking! The curators, Yannick Lintz, recently appointed as president of Musée Guimet, and Rocco Rante, an archaeologist in the Department of Islamic Art at the Louvre, have had access to the collections of eight national and local museums. Some of the artefacts have never been on show even in Uzbekistan because of their fragility or recent restorations. Originally, additional artworks for the Louvre exhibition could be borrowed from the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, but due to the economic and political restrictions on Russia as a result of the ongoing war in Ukraine, that exchange was impossible.

Fig. 2: Detail of the Southern wall of the Hall of the Ambassadors from the mid-7th century CE depicting a sacrificial procession to a Zoroastrian fire temple, most likely on Nowruz, the Persian New Year. Photograph by the author, 2022.

The star attractions of the exhibition include the head of a Kushan prince from the Dalverzin tepa, 1st-2nd century CE [Fig.3] and the Khalchayan statues, both sites found in the valley of the Surkhan Darya (a northern tributary of the Oxus) dating from the Kushan period (40-230 CE). The area was occupied by the Yuezhi, a nomad group who migrated into the region of ancient Bactria in the middle of the 2nd century BCE after they were driven out of their homeland in present-day Gansu province in north-western China by a rival nomad clan. The Khalchayan palace was built in the Hellenistic period in the 2nd century BCE, and was excavated between 1959 and 1963 by the famous archaeologist and architectural historian Galina Pugachenkova (1915-2007). The paintings and almost life-size sculptures in painted clay recovered from the palace, rank among the most remarkable finds of the ancient world. The sculpture of the Khalchayan prince with armour from the 1st century CE [Fig. 4] is characterized by his slightly slanting eyes, long, thin moustache, and the hair tied with a ribbon typical of the steppe horsemen. He holds a sword in his right hand and a cataphract’s armour in his left hand. His armours represent the triumph of the Kushans’ princely aristocracy over the traditional cataphract warriors of the Sakas. In the early 3rd century CE, the Kushan Empire dissolved, probably due to the arrivals of the Huns.

Fig. 3: Head of a Kushan prince, Dalverzin tepa, 1st-2nd century CE. (Photograph by the author, 2022)

Fig. 4: The sculpture of the Khalchayan prince with armour from the 1st century CE. Photograph by the author, 2022.

Another fascinating group highlights the Bodhisattvas found in Dalverzin tepa, dating from the 3rd century CE. One of them is an impressive fragmentary statue of an elaborately dressed Bodhisattva wearing three necklaces, of which the last one opens towards the abdomen and is characteristic of the adornments worn by Buddhist adherents of high rank [Fig. 5]. The lower part reveals his trousers decorated with belts typical of Buddhist costume.

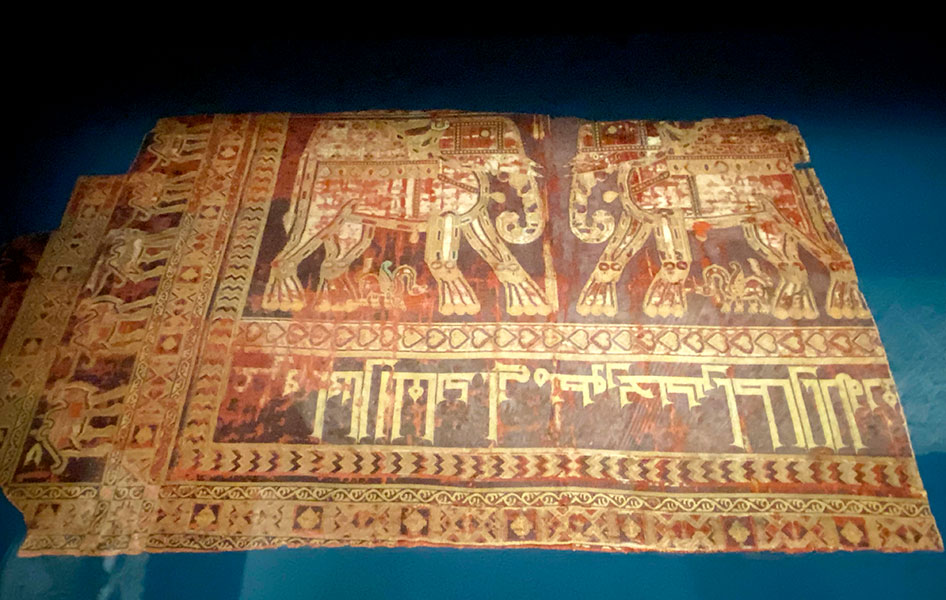

The exhibition also features selected rare textiles. The silk shroud of Saint Josse from 970 is particularly interesting [Fig. 6]. The cloth protected the relics of Josse, a seventh-century Breton saint. The largest fragment is decorated with two elephants facing each other under which are two small, long-necked Chinese dragons. Camels are depicted on the borders as though in a moving caravan. The Arabic text reads ‘Glory and good fortune to the Qa’id Abu Mansur Bakhtekin, may God grant him long [life]’. This textile piece epitomises the complex cultural interactions along the Silk Roads in which Indian, Chinese, and local Zoroastrian visual vocabulary mixed. The Arabic inscription in the linear Kufic script marks the shift towards the Islamic history of Central Asia that starts as early as the 8th century CE with the Muslim conquest of 705, when Qutayba ibn Muslim became the governor of the historic province of Khurasan.

Fig. 5: Statue of a Bodhisattva found in Dalverzin tepa from the 3rd century CE. Photograph by the author, 2022.

In the early decades of the Arab conquest many Zoroastrian and Buddhist monuments were burned by the invading armies. The exhibition showcases one of the most fascinating restoration projects conducted by the French restorer Delphine Elie-Lefebvre at the State Museum in Samarqand. The Kafir Qal’a gate consists of several fragments of carbonized wood that has been subjected to very high temperatures and very little oxygen, highly unusual circumstances that have allowed the mineral matter to be preserved. The door reveals a complex composition depicting the seated four-armed figure of Nana, the widely venerated Sogdian and Bactrian goddess of prosperity, the equivalent of the Iranian goddess Anahita, surrounded by tiers of musicians, priests, and gift-bearers reflecting the social life of the Sogdians prior to 712.

Gradually, the city of Samarqand became the capital of several powerful Islamic empires that conquered larger parts of Central Asia. One of the most prominent and aesthetically sophisticated family that ruled across the Silk Roads are the Timurids. Their dynastic founder Amir Timur (r. 1370-1405), known in the west as Tamerlane, led numerous military campaigns from his capital city of Samarqand and surrounded it with villages bearing the names of the largest Islamic capitals: Sultaniyya, Shiraz, Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo. Timur and his descendants employed monumental architecture as a tool to legitimize their rule on a grand scale and to assert themselves as heirs to major Islamic empires. The exhibition features a fantastic wooden inlay door from around 1425 created by Timur’s grandson Ulugh Beg (r. 1409-1449) for the Timurid dynastic mausoleum of Gur-i Amir, the family burial ground.

Fig. 6: Silk Shroud of Saint Josse from 970 CE. Photograph by the author, 2022.

What is rather puzzling is the size and scale of the information on the Timurids provided by the curators. Both Timur and Ulugh Beg, who are highly regarded as the founding fathers of the Uzbek nation, are diminished to stickers on the wall the size of an index finger. Even if the limited exhibition space could not provide enough exposure, there could have been other more respectable ways to tell the stories of their glorious reigns by a world-renowned museum. What is even more disturbing are the images used for the two historic figures. The curators have decided to use portrait busts created by the Russian anthropologist Mikhail Gerasimov in 1941. Gerasimov was commissioned directly by Stalin to exhume the skeletons of the Timurids and to reconstruct their busts in order to prove the ethnogenetic origins of the Uzbek nation and to attribute the burials in the Timurid mausoleum to the male descendants of the dynasty. Gerasimov’s expedition in Samarqand is regarded to this day as a highly controversial desecration of the entombments and as an assault on Islamic burial traditions. It seems that neither the French nor the Uzbek organizers were bothered to reflect on the accuracy of the historic truth as any information on Gerasimov is missing.

The purpose of the exhibition – to transport the viewers to the civilizations in the heart of Central Asia – seems to be fulfilled by the quality and variety of the 170 artefacts depicting Zoroastrian, Buddhist, Sogdian, and Islamic masterpieces. Yet the general European connoisseur is given very limited historic context in which to place these artefacts. The exhibition catalogue, published only in French, features exclusively French, Russian, and Uzbek authors, an agreement made by the Louvre and the Art and Culture Development Foundation. It provides short essays on the key periods highlighted in the exhibition and remains an important contribution to the study of the material culture along the Silk Roads.

In connection with the exhibition, a documentary directed by Jivko Darakchiev entitled “A Timeless Journey in Uzbekistan” was created in collaboration with the Louvre. The film was aired on 27 November 2022 on the Arte TV channel and can be viewed here. It echoes the archaeological discoveries done by the Soviet scholars in the 1950s and 1960s, and links the artefacts to the actual modern history of Uzbekistan.

Dr. Elena Paskaleva is an assistant professor in critical heritage studies at Leiden University. She teaches post-graduate courses on material culture, memory and commemoration in Europe and Asia. Dr. Paskaleva is also the coordinator of the Asian Heritages Cluster at the International Institute for Asian Studies. E-mail: elpask@gmail.com