Shadow Neighbourhoods: The Street Dwellers and Vendors of Escolta Santa Cruz, Manila

The Manila research team for the Southeast Asia Neighbourhoods Network (SEANNET) considered how urban redevelopment and gentrification alter the configuration of neighbourhoods.

Our essay title suggests the complex relationships between formal and informal systems and structures in the city and how they frame and mediate exchanges between social groups. 1 These groups include ourselves as researchers, who were initially outsiders to this specific neighbourhood context.

We did our first site visits to Escolta in late 2016 and proceeded to work with our women partners from early 2017 through the middle of 2020. These women are ‘neighbours’ in Escolta who occupy various spots on the sidewalk fronting commercial shops as well as areas beside an estuary. This corner of Plaza Sta. Cruz was a busy thoroughfare, situated at the intersection of a church, a commercial bank, fast food restaurants, and jeepney transport points. While we became acquainted with a number of women from our early site visits, our main collaborators were seven women who were third- and fourth-generation residents of Sta. Cruz, the district where Escolta is located. These women managed to keep their ‘spots’ in Escolta by maintaining informal concessions with fellow street dwellers and vendors, building owners, and their suki (“loyal customers”). These relationships also included tenuous ones with authorities, whether local politicians, police, the clearing operation squad of the local city government, or staff of the social welfare department. We were interested in how these negotiations shaped this neighbourhood of women, one formed around strategies and tactics of neighbourliness and attitudes of being neighbourly. We eventually surmised that theirs is a neighbourhood beyond ownership, a neighbourhood beyond property.

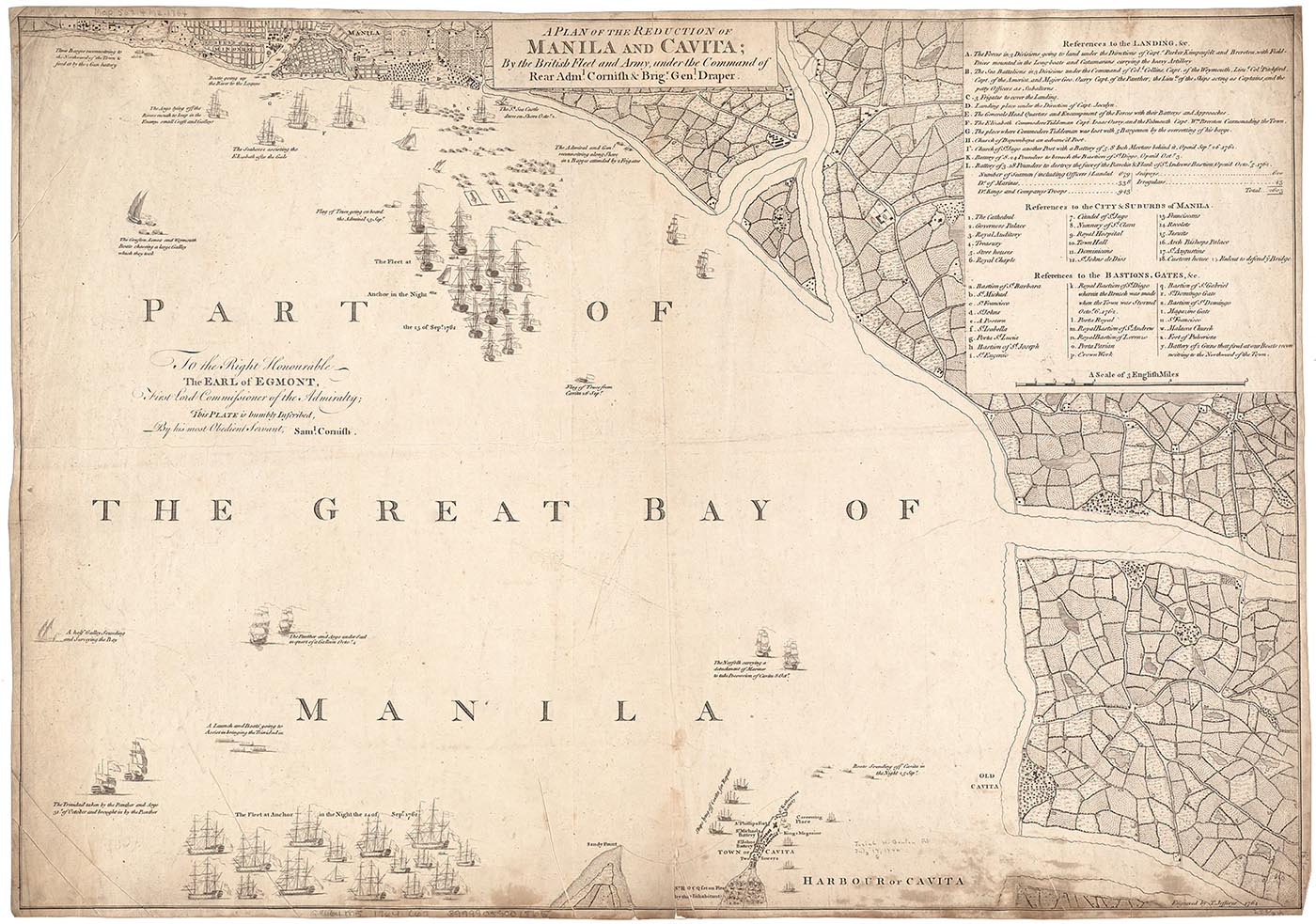

Escolta is a street corridor connecting the districts of Quiapo and Santa Cruz in Manila. It used to be a thriving commercial strip linking the Pasig River to the walled city Intramuros, and to busy Chinatown, Binondo. 2 Manila flourished as a port city from the galleon trade between 1565 and 1815 [Fig. 1]. Even then, Escolta housed warehouses and bodegas for commercial goods. 3 The city was heavily bombed during the Japanese occupation, and Escolta fell into ruins. It had a brief revival in the 1950s and 1960s but fell into dereliction in the 1970s, when Manila was overshadowed by rising commercial districts, primarily those in Makati City and Quezon City.

Fig. 1. A plan of the reduction of Manila and Cavite, 1764. Reproduced under a Creative Commons license, courtesy of The Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library on Flickr.

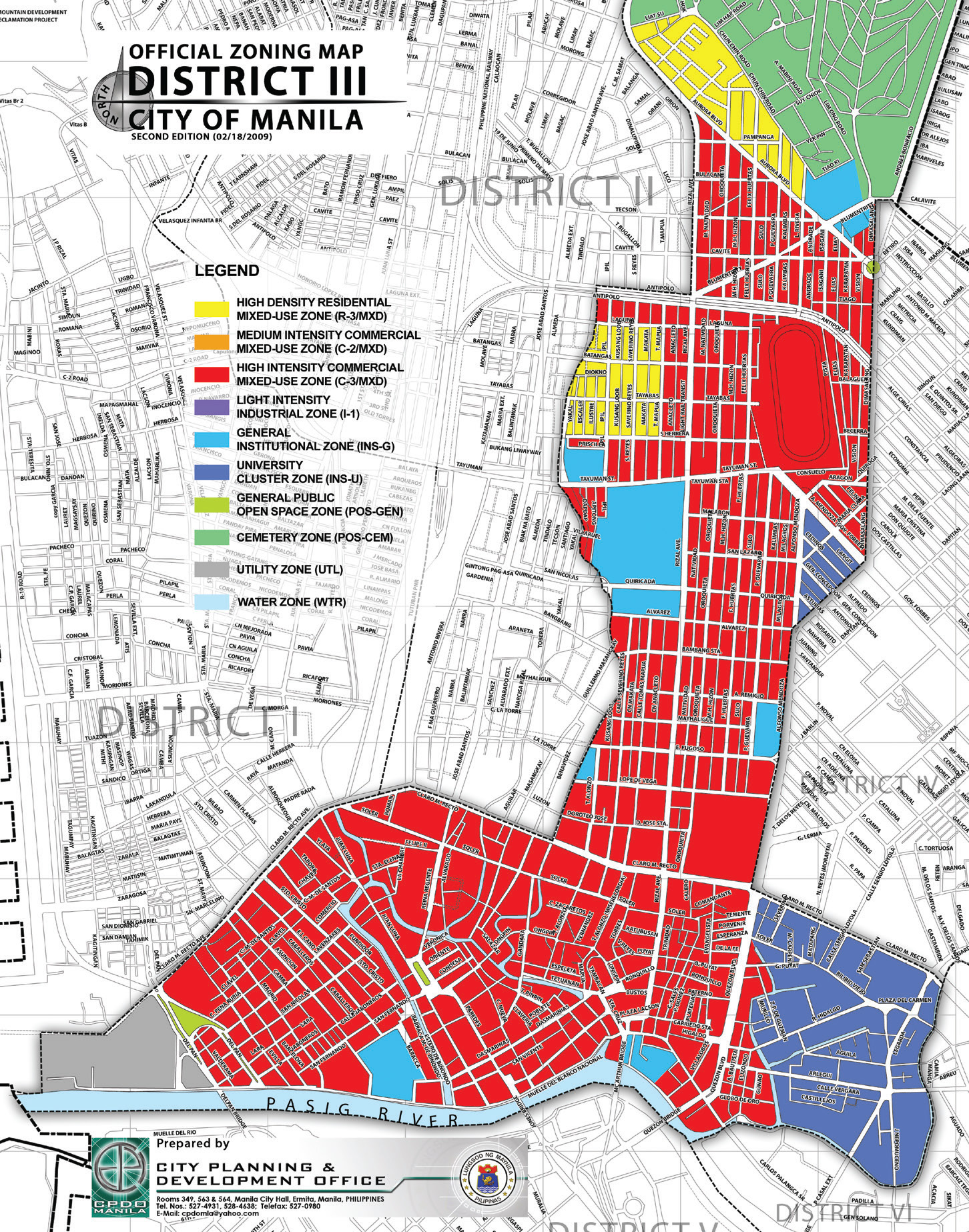

The late 1990s saw efforts in reviving and revitalising Escolta, with the local city government eyeing it as a crucial commercial development corridor. This occurred alongside campaigns to conserve and reuse historic buildings in the area. There were also plans in the early 2000s for Escolta to adopt a mixed-use development plan, which did not materialise. One of the more well-known urban redevelopment projects of this period was Revive Manila, conceived by Manila mayor Lito Atienza from the early 2000s to 2007. 4

Escolta had long been the focus of an architectural conservation campaign by heritage advocates, as several of its postwar structures were either being demolished or had become derelict. 5 Around 2013 onward, Escolta and other areas in Metro Manila saw a revival through art and cultural events, trendy shops, hip coffee bars and restaurants, bazaars, and street parties. These drew crowds interested in ‘happenings,’ exhibition openings, architecture photography, and art-related events. In Escolta, these centred around the First United Building, which houses a small historical museum, several offices for design start-ups, a space for the art laboratory 98B, a ground floor with booths selling artisanal and vintage products, a coffee shop, a bar, and even a barber shop. 6 At present, Escolta remains a commercial area, albeit less busy compared to other commercial zones in Metro Manila. Most of its buildings remain offices and storage for business. Structures on the fringes of Plaza Sta. Cruz, however, continue to fall into disrepair.

Our practices as educators, cultural workers, and artists inform our interest in the mobilisation of arts and culture in development campaigns. While similar to the local festivals and events organised by the Manila City government’s cultural office, the programs that happened in Escolta unwittingly yet effectively cloaked state and business interests with campaigns for heritage advocacy and local culture promotion, making them seemingly removed from local politics and dominant business interests. These development strategies are often deployed for revitalising derelict areas in inner cities and inform recent trends of transforming old neighbourhoods into so-called cultural hubs, a widespread phenomenon across cities in Southeast Asia.

Neighbourliness Amidst Uncertainty

Our cooperation with our women partners yielded new ways of understanding life on the streets of Manila. Our research allowed us to shift our focus from neighbourhoods as geographically bound units towards an understanding of ‘neighbourliness,’ or what we and our women partners call “attitudes of being neighbourly.” Early studies of Philippine culture identified kinship structure as the primary unit of socialisation in Philippine society. Jocano situated the importance of the family and kinship structure in an agricultural socioeconomic formation, wherein farming becomes “a nuclear-family affair, with the members as the basic working unit.” 7 Residence also provides an understanding of kindred relations: households within neighbourhoods have nuclear families, related by kinship to residents of adjacent dwellings. There were no fixed physical boundaries for neighbourhoods, however. Rather, “it is the quality and intensity of social relationships” that define a household or individual as kapitbahay or kaingod (neighbours). 8 Torres describes the neighbourhood as “the most effective segment of the rural society where collective responsibility and a social member gains from his labor in kind by sharing in the harvest of rice, for example… [thus] normative reciprocal obligations for production are implicit between kinsmen,” while outsiders are not expected to do the same. 9

A lay person’s understanding of neighbourhood would be houses adjoining each other. The Tagalog word kapitbahay literally means a house linked to another or houses near each other. The proximity of housing units or residences is dictated by social class, hence the variation in neighbourhood clusters or configuration: looban is a term often associated with inner city slums; a “compound” is a plot of land with houses for relatives or extended family members; a “village” or a “subdivision” can refer to suburban housing developments, to middle-class housing outside the metropolitan core, or to gated communities in the city. Neighbourhoods in the city are managed through associations whose officers are voted for by residents. Housing projects by the government for military and employees in active service are often configured around blocks. These are considered neighbourhoods, too.

Fig. 2. Map activity, marking sites in Escolta and areas of Manila where our women partners previously lived and worked, April 2018.

During our visits to Escolta, we conversed with, listened to, recorded, and reflected on the lives of our women partners, which they mostly conveyed through narratives and life stories. Our research is grounded in six workshops we designed and facilitated: from our earliest planning workshop as a research group in 2017 to the more recent nutrition and hygiene workshop we had with children in 2019. Our planning workshop addressed concerns regarding cross-disciplinary research in local communities, the conduct of site visits and field work, and the forms of ethnography we wanted to engage. We noted that our primary aim was to mobilise the tools and methods of art to interrogate and analyse the dynamics between culture and urban development as well as the relationships between creative groups, artists, artists collectives, the state, private agencies, lobby groups, and local communities.

The research initially had three smaller projects, which centred on issues of homelessness, precariousness, inclusion, and collective agency. Only two of these pushed through. In 2018, we had a walking tour of Escolta, which included a family history and mapping workshop at the local YMCA led by Alma Quinto. We also hosted a cookout, which included a timeline and personal history workshop at a cafeteria in Escolta led by Nathalie Dagmang. We had preparatory sessions for the local action workshop at the local YMCA in 2019, followed by the country action workshop with members of the different SEANNET research teams in the same year. In March 2020, we worked with children on a workshop about nutrition and hygiene at the Museo Pambata (Children’s Museum). We consistently began our workshops with a review of SEANNET’s research goals, previous activities and interactions, and the levelling of expectations. The workshop method allowed us to work at a scale that was small and flexible, open to greater interaction and intimacy that would have otherwise been difficult on a larger scale. We knew we wanted to move away from the ‘city as laboratory' approach and explore how a grassroots approach can lead to deeper engagements with urban communities.

Fig. 3. Official Zoning Map District III, City of Manila, City Planning and Development Office. (Photo courtesy of Manila City Hall).

We asked what it meant to be neighbourly under precarious and uncertain living conditions. How are neighbourhoods formed in the absence of property? In one of our workshops, a partner named Susan insightfully claimed that they know that changes in the city are inevitable, but that all they want is for their voices to be heard. She hoped “to be part of whatever change will happen in Escolta” (Sana ay kasali kami sa anumang pagbabagong mangyayari sa Escolta). 10 The workshops themselves became significant platforms for these women’s narratives, and for our part, a crucial methodology of learning about the life ways of marginalised communities in cities.

Harnessing the Imagination: Narrative, Immersion, and Participation

Our women partners shared their life stories in the family tree workshop by narrating family histories, describing their daily routines, and reflecting on how their changing fortunes led to their lives on Escolta Street. Similar to this was the timeline workshop from the cookout, where discussions of changes in the city seemed to echo the upheavals in their lives: uncertain livelihood, illnesses, and the theft of their belongings, among other dire events. In one of our conversations, we asked whether they felt they belonged more to the city during the convivial atmosphere of the street parties and weekend markets that took place in Escolta from 2013. Their answers were tentative, as their lives for the most part were ingrained in the day-to-day exchanges they have with workers from Escolta: their suki or those who patronise their goods and services, the manager who requested they look after the environs of a bank or building owners who allow them to set up shop by entrances, to mention a few.

Fig. 4. Escolta map and directory designed for the Escolta Block Party in 2016, 98B Collaboratory

The precarious nature of their lives on Escolta Street illustrates the uneven nature of development and gentrification. The drive to revive Escolta is propped up by the inevitable erasure of communities who barely survive the demands of an increasingly globalised world. This “world of disjunctive flows,” as Appadurai described it “precipitate[s] various kinds of problems and frictions in different local situations.” 11 Yet Appadurai noted that this globalised world also supposes and propels the “role of imagination in social life… a faculty through which collective patterns of dissent and new designs of collective life emerge.” 12 We aim to situate our research in these imaginations of collective life. We want the narratives of our women partners to be “at the heart of our [research] field” and not merely be regarded as “voices from the margin.” 13 Hence, the emphasis on how they understood their lives on the streets: they used the word namamangketa (“living on the street”) to describe their way of life. Namamangketa as well as the vernacular terms used to refer to their relationships to each other as neighbours, surfaced in later sessions of our series of workshops.

Listening and reciprocity were crucial to our exchanges with them. If research can indeed be mobilised to imagine and realise a more emancipatory way of life, we heed the call to focus on how our women partners “understand and experience […] development concepts.” 14 This is the path we look forward to pursuing for the project’s second phase. It is a practice that interrogates existing forms of knowledge and expands the collaborative possibilities of grassroots understandings of the city.

Tessa Maria Guazon, Department of Art Studies, University of the Philippines Diliman. E-mail: ttguazon@up.edu.ph

Alma Quinto, visual artist and cultural worker. Email: quintoalma2013@gmail.com

Nathalie Dagmang, Department of Fine Arts, Ateneo de Manila University. Email: ndagmang@ateneo.edu