Resistance narratives along the Bay of Bengal border-zones and the expansion of Myanmar's rebellion geography

In his celebrated book The Glass Palace, Amitav Ghosh writes of the connected lives and experiences of families that tie the main characters to the lands surrounding the Bay of Bengal and the broader Indian Ocean zone during the last century. When read through the experiences of its more prominent characters, the novel highlights how the bonds of family, commerce, and politics stretched across South and Southeast Asia, linking people to places via circuits across borders and the waterways that bridge monsoon Asia.

Writing about a Burmese temple in north Calcutta, Ghosh relates how the temple became a place for displaced, overseas communities – Gujaratis, Bengalis, Tamils, Sikhs, Eurasians – who grew up or had spent much of their lives in Burma, but had to flee during World War II. The temple had become a place to gather, celebrate Burmese holidays, and to speak in Burmese, which was for many, their mother tongue. Ghosh’s Calcutta was in some ways more connected to Rangoon than it was to Delhi, as result of the characters’ life experiences and movement across the Bay of Bengal.

Bay of Bengal as a region in its own right

For Ghosh, Burma is a place of reference for the book’s main protagonists who move beyond its borders, circulating across the Bay of Bengal, but remain emotionally, psychologically, and culturally connected to it despite settling in different locales and despite official borders. Read from this angle, Ghosh’s The Glass Palace captures the essence of what scholars refer to as ‘inter-Asian referencing’ and provides readers with a more nuanced understanding of how we might understand what being ‘Southeast Asian’ or ‘Burmese’ entails.

The promotion of inter-Asian referencing and the revival of interest in the connections between (and across) South and Southeast Asia is a welcome return for scholars in the field. Scholars have long recognized the enduring interaction between the two regions and the renewed attention towards the Bay of Bengal reminds us of the continuity of broader interconnectedness.1 At the same time, inter-Asian perspectives have also attempted to transcend the regional distinctions that earlier area-studies approaches might have sustained. Just as scholars of borders and borderlands have shifted attention to those terrestrial spaces within and alongside nation boundaries, the adoption of the Bay of Bengal as a unit of study achieves something similar by allowing scholars to re-conceptualize the waters stretching from the southeastern coast of India, to the western coasts of Bangladesh-Myanmar, and down the western coastlines of Thailand and Malaysia as ‘a region’ in its own right.2

Viewing the history of Myanmar within the context of the Bay of Bengal has been useful, especially in the study of early-modern trade, religion, and migration to the Arakan region. In fact, much of Burma’s colonial history might be better understood as a chapter in the broader history of Bay of Bengal connections with Burma. The establishment of British authority over India and neighboring territories alongside and across the Bay is one moment that provides insight into these connections. British India’s creation of British Burma in the late 19th and early 20th centuries amplified pre-existing ties across the Bay but introduced new linkages that altered the intensity of that interaction. Cultural, financial, transport, educational, legal and penal infrastructure produced the means to support exchanges and networks across Madras, Bengal, the Andaman Islands and Burma Province. At the same time this very same infrastructure inspired acts of resistance and empowerment that sought to weaken the connections across the Bay of Bengal border-zone.

Creating a rebellion topography

Resistance to the establishment of these infrastructural systems is one way to trace the interconnections across the Bay. Rather than treating the histories of the Burma Rebellion (later called the Saya San Rebellion of 1930-1932), the Chittagong Armoury Raid (1930-1931) in Bangladesh, and the Malabar/Moplah Rebellion (1921) of southern India within the context of their respective national histories, we might take them as part of a connected history of the Indian Ocean, the Bay, and the infrastructure that linked border-zone communities.3

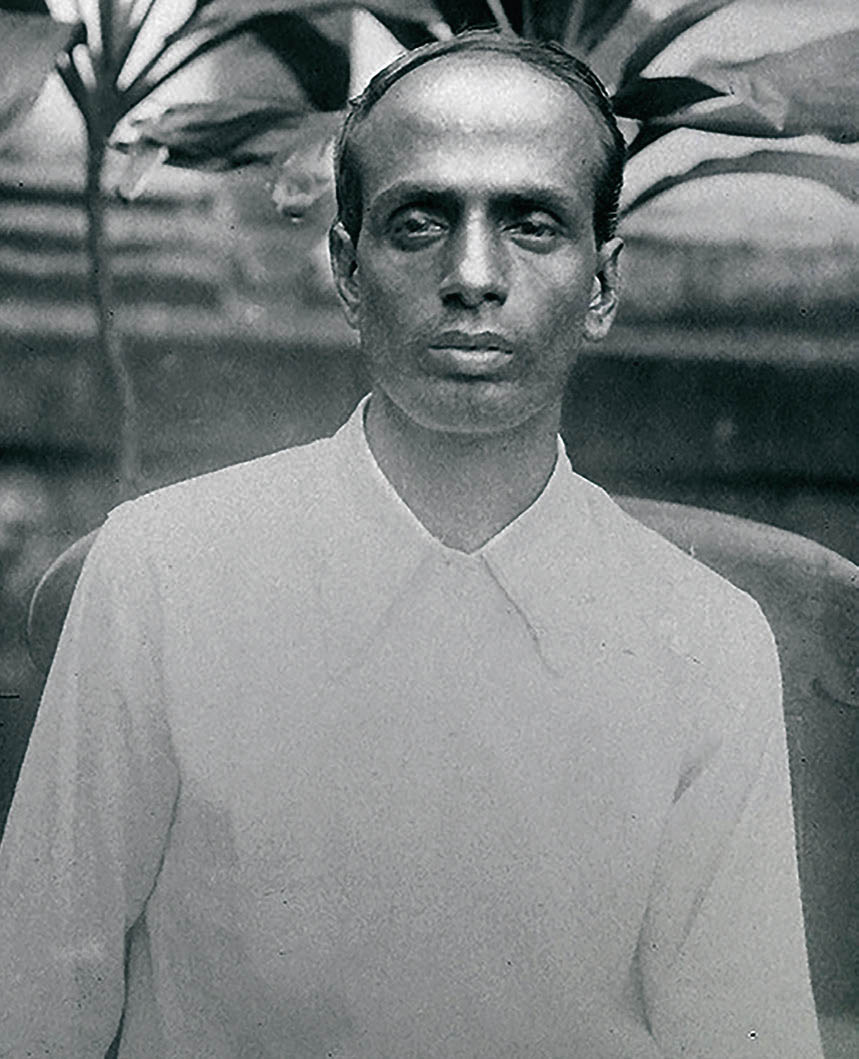

U Ottama with prison uniform.

The Burma Rebellion of 1930-1932, provides a case example of how the Bay of Bengal might serve as a more appropriate spatial and intellectual framework for understanding this event to its fullest extent. While classic studies applied comparative approaches that expanded how the rebellion could be conceptualized within a regional and global perspective, connecting the series of peasant uprisings in the Irrawaddy river delta region to the histories of Madras, Calcutta, Chittagong, and the Andaman Islands reveals the potential that the Bay of Bengal model offers to Burma Studies. The Burma Rebellion of 1930-1932 erupted in the rice paddy fields of the Irrawaddy river delta region at the height of the worldwide depression and the maturing of anti-colonial nationalism throughout the British Indian world. Galvanized by a mixture of socio-economic, cultural, and political grievances, rural rice cultivators, political monks, and grassroots activists took their frustration out on colonial infrastructure and local representatives of the colonial state.

Officials at the time regarded the series of uprisings as a political movement aimed at overthrowing the British and resurrecting the now defunct Burmese monarchy, which had been dismantled following the annexation of the kingdom in 1885. By 1930, rumors circulated that a prophesized min-laung (or pretender king) had returned to reassert the country's sovereignty and restore Buddhism, compelling many to believe that the alleged leader of the rebellion, a former healer and grassroots activist named Saya San, would protect them from harm via his magical incantations, charms and protective tattoos. As local police forces were unable to cope with the size and breadth of the outbreak, Rangoon authorities requested military support from across the Bay in order to restore order. Special counter-insurgency legislation and emergency powers provided the Burma government with the rationale to arrest and prosecute detainees under the jurisdiction of special tribunals.

Surya Sen before 1934.

At first, local authorities were convinced that a Revolutionary Bengali Party had radicalized student groups in Rangoon and added local nationalists to a broader network of revolutionaries that stretched across the Bay of Bengal. While this narrative was contested by local politicians, the connections to Bengal's anti-colonial activities were entrenched; legal and ethnographic assertions were made to create a rebellion topography that stretched across the north-eastern and eastern coastlines of the Bay of Bengal.

It would not be the first time that Bengal was used as a reference to understand rebellion in British Burma. Authorities in Rangoon also attempted to connect the 1930 Chittagong Armoury Raid to revolutionaries in Bengal and Burma. Burma’s most celebrated ‘political monk’, U Ottama, was also linked to sympathetic political groups in British India and other parts of Asia. Viewed from this angle, there is much room to consider how anti-colonial movements and sentiments in British Burma were associated with groups and conversations beyond its borders. While the Burma Rebellion of 1930 is almost exclusively examined within the context of Myanmar’s national history, exploring how it was viewed by, and connected to, overseas communities in Calcutta, Chittagong, and the Andaman Islands – where convicted rebels were sent – is one key thrust of future research.

Maitrii Aung-Thwin, Associate Professor, Comparative Asian Studies Program/Asia Research Institute/Department of History, National University of Singapore. hismvat@nus.edu.sg