Resistance and “PerforMemory” amidst Pandemic-era Anti-Asian Hate: Unsettling Chronologies of Exclusion at Angel Island

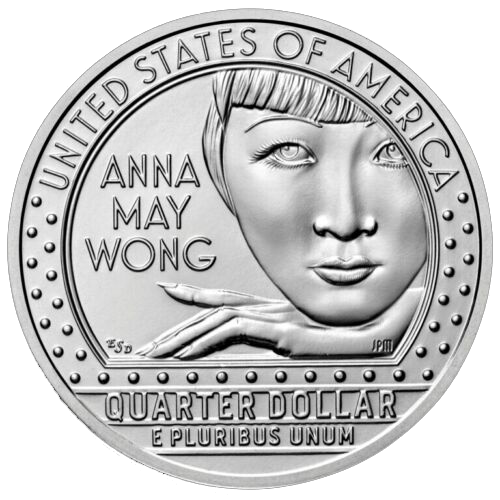

In October 2022, Los Angeles-born actress Anna May Wong (1905-1961) became the first Asian American woman to appear on US currency. The “Anna May Wong Quarter” was the fifth coin in the “American Women Quarters Program” that also featured author and activist Maya Angelou (1928-2014), astronaut Sally Ride (1951-2012), Cherokee Nation Chief Wilma Mankiller (1945-2010), and suffrage leader Nina Otero-Warren (1881-1965). Wong’s inclusion in the series was as much a recognition of her professional achievements as it was an acknowledgement of the hardships Wong had faced in Hollywood amidst “yellowface” practices and anti-miscegenation laws.

From the mid- to late 19th century onwards, discriminatory measures were enforced against the Chinese in the United States at both state and federal levels. In addition, during the Exclusion Era (1882-1943), “Chinese laborers” – referring to “both skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining” – were banned from entering the United States. The 1882 Exclusion Act was the first major US federal law that denied entry and citizenship to an “ethnic working group” because it allegedly threatened “the good order of certain localities.” 1

Fig. 2: Anna May Wong Quarter. (Source: US Mint website)

The year 2022 marked the 140th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act. A series of events in the San Francisco Bay Area revolving around the Angel Island Immigration Station re-engaged with questions pertaining to exclusion, migration, race, and incarceration amidst a new wave of anti-Asian hate crimes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, renewed immigration restrictions and border controls brought debates on immigration back to the foreground. This piece looks at two of these initiatives more closely and, drawing on Catherine Choy and Layla Zami, makes two central points. Firstly, it argues that these initiatives employ creativity as a form of resistance against Asian exclusion. In her recent book, Asian American Histories of the United States, Catherine Choy highlights three related themes in Asian American histories of the United States, namely “violence,” “erasure,” and “resistance.” Resistance, in her view, is not just “reactive” – it is also a “creative force” that is “inextricably linked to the Asian American imagination.” Individual expressions of creativity can meet and traverse with collective expressions, as well as instigate action across generations. 2

Secondly, the piece argues that these expressions of creativity are manifestations of what Zami has termed “PerforMemory”: they “contemporize the past” and as such function as both “a form of expression and an intervention.” “PerforMemory” brings together “memory, movement and resistance” and thereby turns memory into “a site of moving resistance.” 3 Zami uses the concept of “PerforMemory” primarily for dance choreographies that offer a powerful reinterpretation of history against institutionalized memory. However, movement does not have to be restricted to bodily movement per se, but can also include the fluidity of music, images, the spoken word, or the choreography behind rituals. Relevant for the “PerforMemory” acts centering on Angel Island is that performers “circumvent chronology”: memory becomes entangled with other forms of narratives and performances occur within “the ‘present-tenseness’ of the showtime,” thereby connecting with the past “outside of conventional chronologic and geographic boundaries.” 4 To understand the centrality of Angel Island in the creative acts discussed here and how they challenge existing chronologies, the piece first outlines the history of Asian Exclusion and the place of Angel Island Immigration Station in it.

Asian Exclusion and the Angel Island Immigration Station

Amidst the global gold rush, around 325,000 Chinese from southern China made their way to the settler colonies of North America and Australasia between 1850 and 1900. 5 Furthermore, the 1868 Burlingame Treaty between the United States and China guaranteed mutual migration between both countries and enabled the US to acquire Chinese labor for the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. With rising Chinese immigration and mounting economic crisis in the US, however, various constituencies began to debate immigration restrictions and citizenship rights. 6 The 1882 Act would initially last for ten years but was renewed in 1892 and 1902 and made permanent in 1904. In 1917, ethnic exclusion was furthermore expanded, denying entry to those residing in the “Asiatic Barred Zone.” It was only in 1943, with the US entry into WWII as China’s ally, that the Exclusion Act was repealed, but a national origins quota allowed only 105 Chinese to enter yearly. At last, in 1965, Congress passed the Hart-Cellar Act, which eradicated “race, ancestry, or national origin” as the foundation for immigration. 7

Fig. 3: Angel Island Detention Barracks View. (Photo by the author)

Today, Angel Island in San Francisco Bay is a California State Park popular with hikers for its spectacular views of San Francisco, Marin County, and the iconic Golden Gate Bridge. Between the Civil War and the Cold War, however, the island served as a military base, a quarantine station to fumigate foreign ships and isolate passengers, and an immigration station. During WWII, it also functioned as a prisoner of war (POW) processing center for, among others, Japanese and German POWs. Hundreds of thousands of immigrants from over 80 countries were detained at Angel Island between 1910 and 1940 after arriving in San Francisco by boat. Europeans and first-class passengers generally received preferential treatment, whereas Chinese were specifically excluded following the Exclusion Act. They were detained for a period of a few weeks up to, in rare cases, nearly two years. For example, a stone in the memorial wall outside the Immigration Station reads: “Lee Puey You Gin, Longest Detainee of 20 Months—A Rice Bowl of Tears Nurtured.” Admission was only gained after a long and thorough investigation process, especially because some Chinese immigrants attempted to circumvent Exclusion by “buying” places as pretend-relatives of legal Chinese immigrants, also known as “paper sons” (and daughters). Case files show, for example, that Chinese immigrant Chiu Yook Lon had to answer 143 questions before being admitted. 8 Questions detainees were asked included: “How many steps are there to your front door?” or “Who lived in the third house in the second row of houses in your village?” To ensure that answers matched, detainees would rely on coaching books and notes smuggled in by kitchen staff or by bribing guards. 9

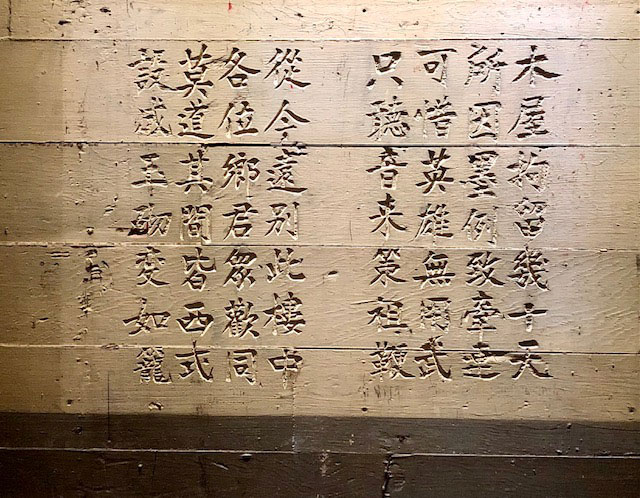

While Chinese immigrants constituted the largest group of detainees at Angel Island (an estimated 100,000), other notable population groups at Angel Island were Japanese (est. 85,000), South Asians (est. 8000), Russians and Jews (est. 8000), Koreans (est. 1000), Filipinos (est. 1000), and Mexicans (est. 400). The Immigration Station at Angel Island “was designed with exclusion, not admission, in mind” in service of the Chinese Exclusion Laws and with Chinese being “singled out for long detentions and intense interrogations.” 10 This explains why Angel Island, despite hosting detainees from many different countries, has a special place in Chinese historical memory. Its Immigration Station is also widely known through the more than 200 Chinese poems that were carved on the walls of the detention barracks by detainees, the discovery of which led to the movement to preserve the Station.

Fig. 4: Bunk Beds Angel Island Detention Barracks. (Photo by the author)

Even though the Chinese Exclusion Act is probably the most well-known Exclusion Law, other Asians were also banned from the United States and discriminated against in the decades that followed. Apart from the “Asiatic Barred Zone” mentioned above, in the 1920s, Japanese and Indian immigrants became excluded from US citizenship. State laws furthermore made non-US citizens ineligible for land ownership and outlawed interracial marriage. Hence, the Angel Island Immigration Station Museum also displays, among others, the exclusion of South Asians. For example, its exhibit features the front page of the August 1910 issue of The White Man, a magazine “devoted to the movement for the Exclusion of Asiatics.” The front page refers to “the Hindu” as “the next big crisis after the Chinese.” Restrictions against “Asiatics” were also justified as health protection measures such as preventing the spread of hookworm infections. Given Angel Island’s place in the history of Asian Exclusion and immigration controls more generally, creative resistance in 2022 tied current anti-Asian hate not only to the Chinese Exclusion Act, but also to this broader history of exclusion.

Unsettling chronologies of exclusion at Angel Island in 2022

In May 2022, on a hidden corner of a wall in San Francisco’s Chinatown, a poster urged passers-by: “Standing Strong for Inclusion: Join Us as We Commemorate the 140th Anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act.” The poster was shared online among Chinese communities, such as on the website of the Bay Area Chinese Genealogy Group (BACGG), a network of “family historians” in the San Francisco Bay Area. Its website stated: “Today, we are experiencing a dismaying rise in violent attacks on Asian Americans. We cannot afford to stay silent; we must instead stand together to stop the hateful legacy of this Act that our community continues to face.” 11

Fig. 5: Angel Island Detention Barracks Poem Known as 'Poem 135'. (Photo by the author)

In this statement, the history of the Exclusion Act was tied to the current wave of anti-Asian hate crimes, and its authors called for commemoration-as-intervention. The “Standing Strong for Inclusion” event that readers were urged to join involved the sponsorship and partnership of the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco, the APA (Asian Pacific Americans) Heritage Foundation, the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, the Chinese Historical Society of America, and others. On the morning of May 6, 2022, a memorial wreath was placed at the Chinese Immigrant Monument at the Angel Island Immigration Station. “PerforMemory” in this case also included the connection of memory, movement, and resistance through light and participation: a “Lighting the Darkness” display consisting of 140 candles, one for each year since the Exclusion Act was passed in 1882, was set up inside the detention barracks during the month of May 2022 on the occasion of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. 12

“PerforMemory” also consisted of moving images: on the evening of May 6, as well as on consecutive Fridays in May 2022, an installation titled “Exclusion/Inclusion” by Felicia Lowe and Ben Wood projected videos about Angel Island onto the walls and guardhouse of the Fort Mason Center for Arts and Culture (FMCAC) in San Francisco. On May 7, at the Chinese Culture Center in San Francisco, two short films by Felicia Lowe, What’s Your Real Name, addressing the history of “paper names” and Carved in Silence, on the experience of being detained at Angel Island, were screened.

Linking past events to current concerns, the screening was followed by a session on present immigration questions. Finally, the program ended with artists Summer Mei Ling Lee and Stephan Xie reading out 140 names of Chinese Americans affected by the Chinese Exclusion Act. As such, the linear chronology of 140 years was also reduced to the “present-tenseness” of the reading ceremony. Finally, following a procession led by Taoist priests, participants were invited to place flowers and photographs at an altar, where musician Francis Wong performed a blessing ritual. The “Standing Strong for Inclusion” poster also called for cross-ethnic solidarity in the form of a conference on “healing and solidarity” around the murders of Vincent Chin (1982) and George Floyd (2020), both of which caused massive outrage and, in the case of the latter, Black Lives Matter organized rallies.

Fig. 6: Poster “Standing Strong for Inclusion.” (Source: Fort Mason Center for Arts and Culture website)

Angel Island was also the focal point of a series of events organized by UC Berkeley’s Future Histories Lab and Arts + Design Initiative in 2022-2023, including courses, public events, exhibitions, and performances. Apart from various UC Berkeley departmental cosponsors and campus partners, the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation was also a partner in the events series. In the series entitled “A Year on Angel Island: Migration Histories and Futures,” Angel Island was a starting point to examine “race in America, global migration, and architectures of incarceration.” Through “arts, design, and historical and landscape interpretation” the series served to “understand current events and envision better futures.” 13 The talks in the series were highly versatile and covered topics such as dance, theater, and incarceration; efforts to preserve the Angel Island Immigration Station; women painters of Japanese descent in Exclusion-era California; South Asian storytelling in Berkeley; Asian American histories of the United States; theater and “paper sons”; the Angel Island poems; and music and storytelling of Chinese Exclusion. As can be seen from these topics, the series put a spotlight on the history of racial exclusion in California and the United States amidst the renewed urgency of border restrictions, anti-Asian hate crimes, and refugee crises.

The series also contained a remarkable array of performances, such as Lenora Lee’s multi-media dance project Within These Walls, performed by the Berkeley Dance Project and directed by SanSan Kwan. This piece had first been performed in 2017 at the Angel Island Immigration Station on the 135th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Drawing on experiences of containment, performance in this context functioned “as a meditation on healing, resilience, and compassion.” 14 Among other performances were In the Movement, which addressed family separation and immigrants’ mass detention, and Angel Island Oratorio, a 60-minute oratorio for voices and strings based on the Chinese poems at the detention barracks. In both of these dance and musical performances, the “temporality of performance” would, in the words of Zami, “contemporize” the past and concurrently serve as a poignant intervention.

Another potent form of “PerforMemory” in the series was that of storytelling. In October 2022, sections of the musical Illegal by Skyler Chin and Sita Sunil were performed inside the Angel Island Immigration Station, combining music, comedy, kung fu, and the spoken word. Inspired by both the Chinese poems at the detention barracks and the experience of Skyler’s grandfather, who arrived at Angel Island in 1923 as a “paper son,” Chin and Sunil wrote the musical during the COVID-19 pandemic as part of a Yale workshop. The musical exemplifies how, in “PerforMemory,” memory is created “as a repertoire colliding and colluding with the archive.” 15 Indeed, the 26 songs of the musical drew on historical records, but by incorporating these into other narrative forms, such as rap, comedy, and song, a “circumvention of chronology” also occurred. Central to the story were the fictional characters Kee Lin, an up-and-coming martial artist, and her “paper brother,” Slim Chin, both of whom fled China in 1926 and were subsequently detained at Angel Island. Historical accounts on which the musical drew include the interrogation processes of detainees, experiences of interpreters at Angel Island, and the Angel Island poems. Chin and Sunil explained how storytelling can be used “to respond to pandemic-era anti-Asian hate, combat prejudice, instigate justice, and inspire empathy.” 16

In conclusion, these events and performances revolving around Angel Island were manifestations of creativity-as-resistance against renewed anti-Asian violence and the erasure of Asian Americans from US history. “PerforMemory” was a way to connect the past to present concerns and future hopes, and it functioned as both expression and intervention. Part of this intervention involved unsettling established linear chronologies by encapsulating memory within other forms of narratives. Similarly, in her own act of resistance, Choy’s Asian American Histories starts in 2020 and moves back in time, with each chapter also moving back and forth in time to expose “multiple temporal origins of Asian American history” and connections and continuities such as Black and Asian American alliances. 17 As such, these interventions urge us to approach present injustices not so much as a linear question of origins as a zigzag question of perceived-endpoints-becoming-origins becoming everything in between.

Els van Dongen is Associate Professor of History at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Her e-mail is evandongen@ntu.edu.sg.