Pulau Ubin Anti-Motor Torpedo Boat Battery: the gun that never was

<p>The National Parks Board and the NSC Archaeology Unit recently launched a research collaboration to investigate the archaeological significance of Pulau Ubin island, located northeast of the main Singapore island. The archaeology team would conduct surveys and excavations on the island over a span of 18 months. In December 2017, the team completed its first field season by evaluating and recording the remains of the Anti-Motor Torpedo Boat (AMTB) military structures. While the documentation has been completed, archival research and analysis are still ongoing to interpret the past use of the site.</p>

Kampong Bahru is a 21m knoll situated immediately west of Sungei Mamam creek along the central northern shoreline of Pulau Ubin. During the Second World War, it was the site of a coastal artillery emplacement designed for two twin 6-pounder guns. These guns were termed AMTB equipment, and typically emplaced near the entrance of harbours in two or one gun configuration. The Pulau Ubin AMTB battery formed part of the Changi Fire Command – a network of coast artillery batteries placed to protect the eastern part of Singapore; specifically, the waterway leading into the Royal Navy base at Sembawang.

The first production batch of twin 6-pounders at the Woolwich Ordnance Factory, UK, were sent to Singapore in 1937. They armed several emplacements in Changi, Pulau Tekong, and Keppel Harbour. However, it is unclear whether the guns for Pulau Ubin arrived in time to see any action. As a result, the emplacements remain in relatively good condition as it did not suffer from direct enemy fire, and demolition by the retreating British Army. Part of the research at the Ubin AMTB was to examine whether any guns were ever emplaced at the battery.

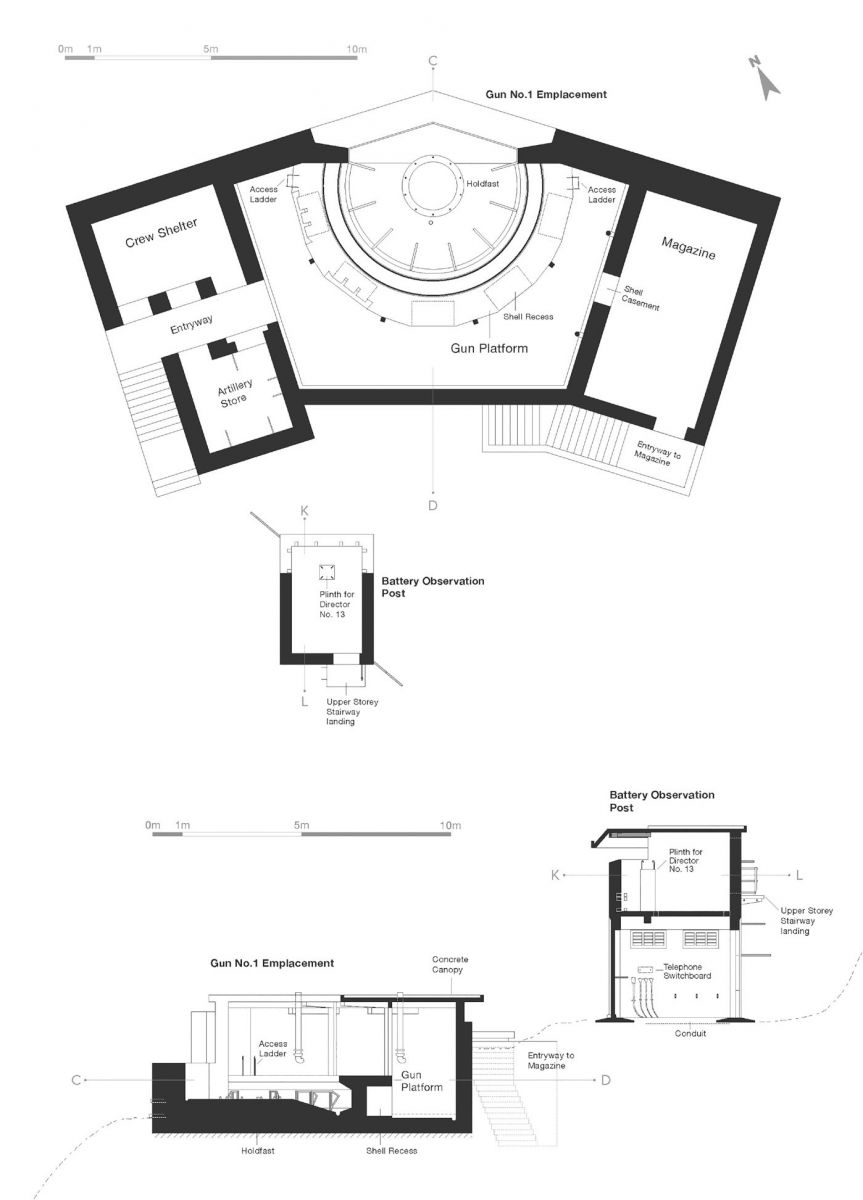

The two gun emplacements of the AMTB were similar in layout (see figs. 1 and 2). The central gun floor area was flanked on the east side by the magazine, and on the west side by a crew shelter and artillery store. Both emplacements were built eight meters apart in a staggered formation on a terraced slope approximately mid-way on the knoll, and facing northeast. Gun no. 1 (see fig. 3) was the first emplacement from the east. Entry into the emplacement was on the west via a corridor situated between the crew shelter and artillery store. Behind each emplacement, stood a two storey (gun no.1) and three storey (gun no.2) battery observation post (BOP) tower. This structure housed equipment and men to command the guns, engines, and searchlights.

In addition to the gun emplacements, the battery also consisted of ancillary buildings such as barracks, toilets, cookhouse, engine room, oil store, storerooms, water pumping station, and searchlight emplacements. They were all built in a compact location on the knoll. A jetty located west of the gun emplacements also served the establishment. The barracks, toilets, and cookhouse have since been demolished. The engine room and oil store were located together on the south-eastern foot of the knoll, out of view from an attacking enemy ship. Both were simple rectangle concrete structures with flat roofs. Approximately 300m downhill from the northeast corner of gun no.1, and at the water’s edge, were three DEL (defence electric light) emplacements (see fig. 4). These concrete structures house fixed beam electric searchlights powerful enough to light up a section of the waterway. These would have allowed the guns to engage intruders at night or in low light conditions.

Although it is unclear if the guns were installed in time for the Japanese invasion, it is evident that the battery was used to some extent. Electrical fittings and other debris observed in one DEL emplacement seem to suggest the occupation of equipment. A telephone communication switchboard was probably installed in gun no.1’s BOP as marks and fittings on the wall indicated so. An engine was in use for a period of time as the ceilings of the engine room were heavily covered in soot. It may be possible that a temporary arrangement was placed pending the arrival of the guns. More research is now being conducted to establish the activities of the site.

This AMTB battery was significant within both local and national context. It marked the technological evolution of coastal artillery in the British Army that started in the 16th century in Britain, and early 19th century in Singapore. If we were to discount British association, the nearby 17th century Johor Lama kingdom located along Sungei Johore just across the straits had fought coastal battles with the Portuguese and Acehnese by employing a wide array of coastal artillery as a part of its defences. The Ubin battery serves as an interesting evolutionary study in this related field of warfare and coastal defences in Southeast Asia.

The substantial remains of the Ubin battery make the site rare as many other coastal artillery gun batteries were destroyed during the war or demolished to make way for development. This surviving specimen remains relatively intact and legible. The battery also formed the larger military landscape of fixed defences that was unique to Southeast Asia. Singapore was after all the most heavily armed colony within the British Empire in terms of coastal artillery. At a local level, the Pulau Ubin documentation project would complement available information regarding the subsistence and lifeways at Kampong Bahru. It would help to answer questions such as whether the militarisation of Kampong Bahru affected or benefited the local community. Despite the shortcomings of the British Army in 1942, the coastal batteries did deter a Japanese seaborne assault, and fulfilled the role it was designed to do.

This article can be found in NSC Highlights Issue #8 (March–May 2018)

Aaron Kao is a Research Officer at the Archaeology Unit, NSC, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, and a member of the Pulau Ubin project. He received his BA from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and has a keen interest in pottery analysis and military history. As a part of the AU team he has excavated many sites in Singapore and Cambodia. aaron_kao@iseas.edu.sg