The Pith Helmet in Chinese Communities: Cultural and Symbolic Transformations

The pith helmet – also known as the "solar topee," “topi,” or “safari helmet” – is a type of hat typically made from pith or cork material. Originally designed to shield the wearer from the sun and heat [Fig. 1], this headgear was adopted by European forces during the 19th century and gained widespread popularity in colonized regions. As such, it has become an iconic symbol of colonialism and is a reminder of the history of imperialism.

Fig. 1: A pith helmet made in Singapore, 1940s. Source: Overseas Chinese History Museum of China (Accession No. C10673).

Interestingly, in China, both Sun Yat-sen (孙中山, 1866-1925) and Mao Zedong (毛泽东, 1893-1976), two of the most prominent figures in the country’s modern history, were known to wear pith helmets in public. This article explores the adoption of the pith helmet in Chinese communities, both within mainland China and beyond, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It will also examine how the helmet’s cultural and symbolic meanings have transformed over time.

The Pith Helmet in Colonialism

The pith helmet has been around at least since the mid-19th century, when European colonial expansion into tropical and subtropical regions necessitated protective headwear for military personnel. The helmet was typically covered with white cloth and featured a cloth band (puggaree), as well as small ventilation holes. It was initially popular among military personnel and soon became widely worn by other Europeans such as police officers, explorers, archaeologists, botanists, and even tourists in Asia and Africa. While the pith helmet was deeply involved in European colonial activities, it also came to reflect a strong physical anthropological colonialism. The belief that light-skinned Europeans were more susceptible to the intense sunlight of the tropics than the natives further perpetuated the notion of European superiority.

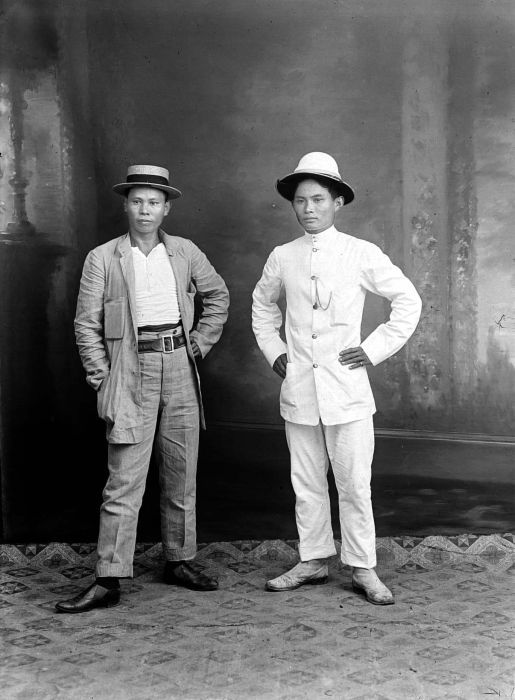

In the mid-19th century, the Dutch East Indies saw the establishment of rubber plantations, which led to the widespread use of the pith helmet among planters. Europeans on these plantations often wore all-white outfits, including a distinctive jacket and trousers, accompanied by a white pith helmet. This attire served to distinguish them from the local labourers and signal their privileged status [Fig.2]. 1 Additionally, the Dutch colonial police force also used the helmet while on patrol in the region, making the helmet a marker of distinction and a symbol of authority.

Towards the end of the 19th century, it became increasingly common for Chinese men in the Dutch Indies and Straits Settlement to adopt the fashion of wearing a pith helmet. This headwear was typically paired with a Western-style white suit known as baju tutup in Indonesian, which featured a low, single-layer collar. This sartorial choice was reminiscent of the outfits worn by the colonial elite, suggesting that Chinese communities were imitating the dress of their colonial overseers.

One example of this fashion trend among Chinese men is a series of photographs featuring employees of the Singkep Tin Company in the Riau Archipelago of the Dutch East Indies. The series was submitted by the company to the Colonial Institute Association in Amsterdam in 1915 in response to a call for visual material of the colony. 2 The photographs included several posed portraits of Chinese employees wearing pith helmets [Fig. 3]. This indicates that the pith helmet had already gained popularity among some local Chinese who had more interactions with the Western community through their occupations as company clerks and officials. Their dress made them distinct from new Chinese immigrants, or xinke 新客 (“new guests”), who stuck to traditional Chinese clothing.

Fig. 3: Portrait of two Chinese foremen of the Singkep Tin Maatschappij, 13 x 18 cm, Source: Tropenmuseum (Accession No. TM-10005290).

The Pith Helmet and the Revolutionary Leader Sun Yat-sen

During the late 19th century, the rise of nationalism in Chinese communities, both within and outside China, was significant. Despite the fact that most of the Chinese men residing abroad were still adhering to the hairstyles prescribed by the Qing government, some Straits Chinese men initiated a movement to cut off their long braids hanging down their backs, a style associated with the Manchu’s rule which they had deemed to be the cause of the nation’s weakness and poverty.

The late 19th century also marked the beginning of Sun Yat-sen’s political career. As the son of poor farmers, he received an education at a missionary school in Hong Kong. By the 1890s, he had attempted to organize overseas dissident Chinese groups against the Manchu rule. One of his target groups was the Straits Chinese. In 1905, Sun Yat-sen visited Singapore to meet with local revolutionary Chinese leaders. An historic photograph was taken at Wan Qing Yuan (later the “Evening Garden”) during their meeting [Fig. 4], wherein Sun Yat-sen is wearing all-white clothing and holding a khaki pith helmet in his hands. Two Singapore-born penarakans (people of mixed Chinese and Malay/Indonesian heritage), Teo Eng Hock (张永福, second from the left in the front row) and Goh Ngo Sow (吴悟叟, first from the left in the back row), are also wearing or holding their own helmets. Teo apparently had his braid cut, like many of the men appearing in this photograph, including Sun.

Fig. 4: Sun Yat-sen holding a pith helmet at Wan Qing Yuan, 1905, 14.8 x 29.3 cm. Source: National Museum of Singapore (Accession No. 2010-03364)

This is the earliest known photograph of Sun Yat-sen wearing a pith helmet, and his entire appearance is notably different from what he previously wore in Honolulu, Hong Kong, and Tokyo. Considering Sun’s situation at that time, it is evident that his attire was an attempt to connect with potential allies and followers of the Chinese communities in Straits Settlements. His clothing represents his efforts to establish a rapport with locals and garner resources through their financial support. His efforts paid off: the Singapore chapter of Tong Meng Hui (The Chinese Revolutionary Alliance) was successfully founded upon his visit, which assumed a pivotal role in the 1911 revolution to come.

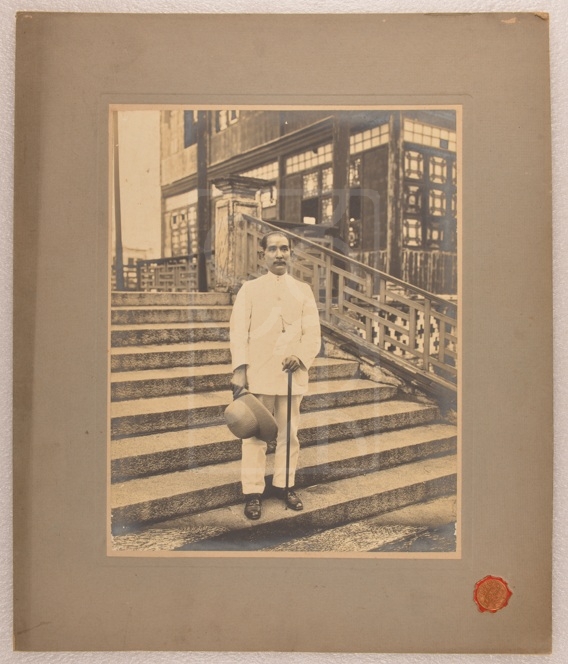

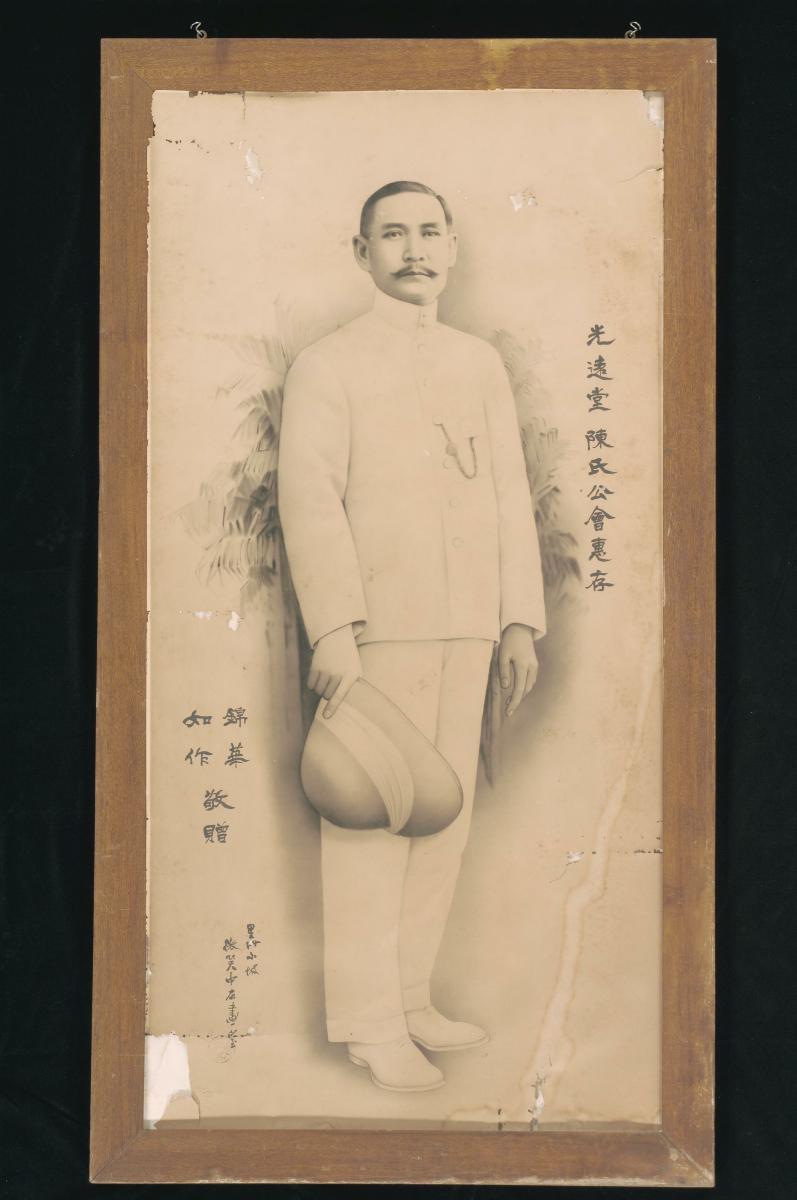

The outbreak of the 1911 revolution marked the collapse of the Qing dynasty and resulted in the founding of the Republic of China the next year. Sun Yat-sen was a protagonist in this revolution and returned to China as its leader. From the late 1910s until his death, Sun frequently appeared in public wearing a unique style of pith helmet with an all-white suit [Fig. 5]. 3 The helmet became a part of his public image in Chinese communities, to the extent that even after his death, he was commemorated in Singapore as such [Fig. 6]. 4

Fig. 5: Sun Yat-sen arrived at Guangzhou, July 17, 1917. Source: Shanghai Sun Yat-sen’s Former Residence Museum (Accession No. unknown).

Fig. 6: Portrait of Sun Yat-sen, 1930s, 151 x 75.2 cm. Source: National Museum of Singapore (Accession No. 2009-01786).

The adoption of pith helmets by Chinese revolutionary leaders and Chinese men returning from overseas was a symbolic repudiation of traditional Chinese customs. It served as a manifestation of their allegiance to revolutionary principles, following in the footsteps of Sun Yat-sen and others. Over time, the pith helmet underwent a remarkable transformation from a colonial emblem to a cultural icon of revolution and nationalism. Its significance was underscored on August 28, 1945, when Mao Zedong flew from Yan'an to Chongqing, the wartime capital of China, to deliberate about the future of the Communist Party of China (CCP) and its relationship with the Kuomintang (KMT) in the aftermath of the second Sino-Japanese War. Mao's unusual decision to wear a pith helmet during his departure was likely deliberate, as he was well aware that what he wore would be the focus of media attention [Fig.7]. The headgear elicited a natural association with Sun Yat-sen, and by extension, with his political legacy, further cementing Mao's credentials as a successor to Sun.

Fig. 7: Mao Zedong (second from the left) in a pith helmet before his departure from Yan’an to Chongqing, August 28, 1945. Source: Chinese Photographers Association.

The Pith Helmets as Chinese Goods

Although it is challenging to assess Sun’s influence on the headgear of the masses, the popularity of pith helmets in Chinese communities since the 1920s was a testament to the success of his image. Local pith helmet hatters burgeoned in Asian cities such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok, and Guangzhou in the 1920s. Most of these were owned and controlled by the Chinese. 5 The use of alternative local materials instead of pith and cork made the helmets cheaper and more accessible to the general public, transforming them from expensive European imports into affordable and fashionable items. As a result, the pith helmet became increasingly indigenized, and its exotic status weakened.

With the development of national industry, the production of pith helmets underwent a transformation, with the indigenization of production and the use of alternative materials. The pith helmet became a “national good,” associated with strong nationalist sentiment. One example of this transformation is seen in the pith helmets produced and advertised by the rubber company of Tan Kah Kee (陈嘉庚, 1874-1961) in the 1930s. The advertisement is a rhymed poem, part of which reads: “They are half the price (of the imported ones). But how can they come so cheap? / Crafted by the hands of Chinese female workers, they should be promoted to recover the losses of our national interests. / Please show your sympathy and support. Make a purchase (of our products) and stand with us.” 6

The advertisement for the pith helmets emphasized their low cost and the fact that they were made by Chinese female workers, thus promoting the idea of supporting Chinese national industry, even though Tan’s business empire was rooted in Singapore. By linking the production of pith helmets with Chinese nationalism, the advertisement shifted the cultural symbol of the helmet from “colonialism” to “revolutionary” and ultimately to “national” and “patriotic.” This is also the transformation trajectory of this headwear in Chinese communities until it gradually became outdated in 1950s.

Wang Wenxin studied in China and the Netherlands, and is currently Associate Senior Researcher at the Overseas Chinese History Museum of China in Beijing. Her research focuses on China’s cultural history and its interactions with other world regions in history. Email: wangwenxin1986@gmail.com