Photography and the Documentation of Memory

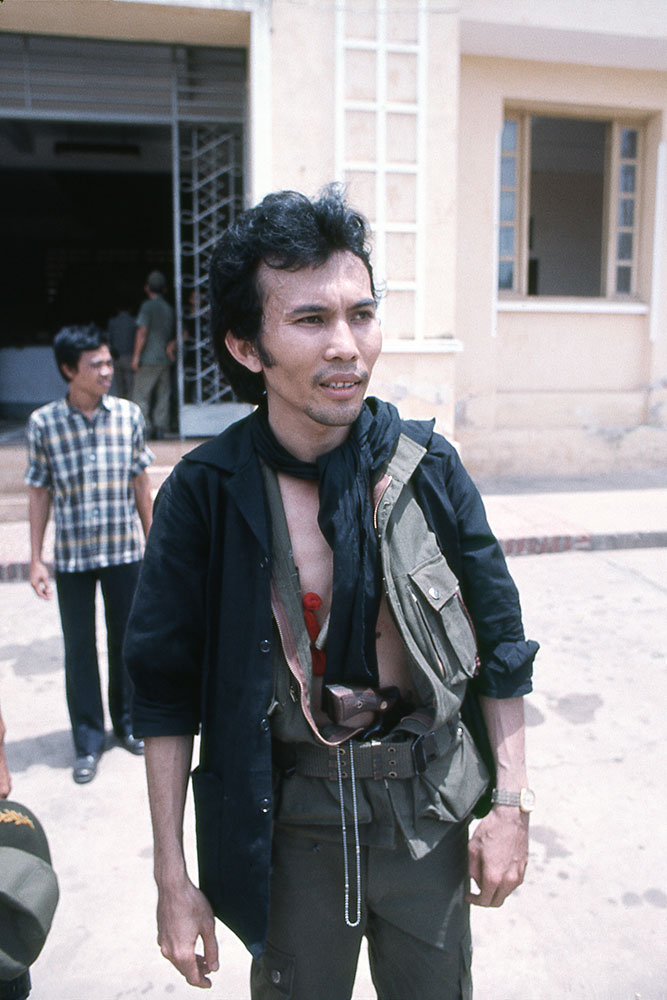

A photo is an instant in time. What came before it and what came after, we may not know, and except to the person who took it, the image itself might remain a mystery open to many interpretations. Even then, memory is such a slippery and malleable creature that the photographer himself may begin to question its veracity. I’m thinking of the “iconic” image of the “Khmer Rouge soldier” on 17 April, 1975, in Phnom Penh, brandishing his pistol and screaming at people [Fig. 1]. A chilling image of unbridled violence. Yet let’s look again. There’s something about his dress that is not Khmer Rouge. If you look closely at his finger, it is not on the trigger of the gun. His mouth is wide open, and the screen shot freezes his expression at the moment it appears most menacing.

The "iconic" man in Fig. 1 has been wrongly identified at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) as Hem Keth Dara, the leader of the Monatio (Mouvement Nationale), a ragtag group of some 200 students and youths hastily assembled – possibly by President Lon Nol’s brother Lon Non – as a “welcome committee” for the Khmer Rouge. They wore nicely tailored black uniforms and were initially mistaken for the real Khmer Rouge. The man in the picture is certainly not Dara. I knew him personally, so it particularly annoys me that he has been reduced to this image of mindless violence. Dara was executed together with his family and followers, probably on the same day that this picture was taken [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2: This is the real Hem Keth Dara, leader of the Monatio, much more elegant and fashionable than Figure 1. (Photo by Naoki Mabuchi, 1975, courtesy of Watana Kiuchi)

I started taking photos in Laos in 1970, then in Cambodia. I was not a photographer, although I was consumed by enthusiasm for taking photos. I was a teacher at an English language school (ETAPP) in the Khmer Republic. A colleague shared an apartment with a Japanese photojournalist, Naoki Mabuchi, who fueled my interest and provided me with film when I couldn’t get any. It was bulk-loaded, mostly black-and-white Kodak Tri-X. My camera (I only had one – the mark of an amateur) was a Pentax Spotmatic. In those days, most professional war photographers used Nikons, tougher and easier to change lenses. I had a regular 50mm 1.4 lens, a short 105mm telephoto, and a 35mm wide angle. There were no darkroom facilities available. I had all my films processed in a local photo shop. They did a decent job but it depended on the freshness of the chemicals. Sometimes the negatives were under- or overdeveloped. It was fortunate that we scanned and digitalized them in 2015 because a few years later some of them bubbled up and died when I took them out of their sleeves.

Fig. 3: Mr. Bigsmile. ‘This was the man who drove me to Banteay Chhmar on his motorbike, actually the first Cambodian I met.’ (Photo by Colin Grafton, 1972)

The scarcity of film made me focus, as if I was using ammunition in short supply. In two years, I ended up with only a few hundred pictures. I had no agenda. I was not planning to “do” anything with them. There was no idea of reporting or documenting history. Until the last month or so of the war, when movement became more limited, professional photographers were going out to the front line every day, risking their lives to capture battle scenes. They spent little time in town. Occasionally they captured powerful images on the battlefield, but if you look at their contact strips, you see endless series of puffs of smoke in rice paddies. I was taking “safe” pictures in the streets, and later in the countryside, of ordinary people and everyday life [Figs. 3-4]. When I left Phnom Penh in April 1975, ten days before the city’s fall, I had all the negatives. Naoki Mabuchi drove me to the airport. He was staying to cover the entry of the Khmer Rouge. 1 I intended to return if possible. Then an ominous curtain fell over Cambodia for nearly four years. Looking at the photos, I often wondered what had become of the people.

Fig. 4: Girl on a bicycle. ‘I took one more photo of this girl, but in the second photo she lowered her eyes. Only the first one captured that look.’ (Photo by Colin Grafton, 1973)

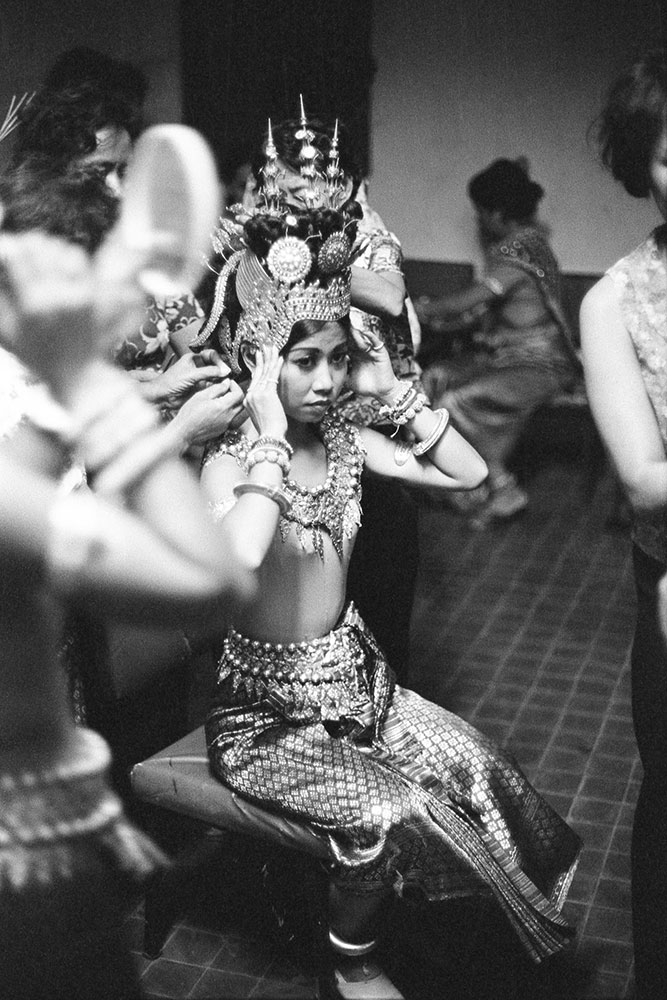

In 2007, a dancer appeared in Tokyo, where I was then living. Somehow, she had one of the photos I had taken of her in the dressing room of the National Theatre 33 years before [Fig. 5]. It was a delightful surprise and a wake-up call. She had survived. Her name was Om Yuvanna. I had to go back and find out more about the other dancers. 2 In 2011, I met my old friend Naoki. He was in bad health. We talked about the fact that neither of us had shown our photos in Cambodia and decided to put together a joint show. But six months later, Naoki died. His wife gave me a box of his slides. 3 I moved to Phnom Penh in 2014 and deposited scanned photos at Bophana Center, an audiovisual resource archive. In 2016, my wife Keiko Kitamura and I produced an exhibition of 20 Dancers images, based on one single film that I had shot at the last performance of Khmer classical dance at the Suramarit National Theatre in 1974. Then we did Phnom Penh Before The Fall in 2017. Bophana envisioned an “art” exhibit of similar scale to the first, but I wanted this to be a documentary project, so we ended up with over 100 prints. Next was an exhibition of Naoki Mabuchi’s work from 1974 to 1983.

Fig. 5: Om Yuvanna. ‘I walked into the dressing room and took this photo.’ (Photo by Colin Grafton, 1974)

While talking about the scarcity of visual material from the Lon Nol era, Bophana Center director Chea Sopheap showed us some photos donated by two French peace corps volunteers, Serge Guérin and Daniel Yvetot. He asked us if we could curate an exhibition using these and other material from Bophana’s archives. The resulting Glimpses of the Khmer Republic consisted of work from six different photographic sources. We called the exhibition “glimpses” because there were so many gaps. Guérin and Yvetot had provided information about themselves, but nothing about the photos they had deposited. We could not even be sure they had taken them. There were prints, but no negatives. However, their pictures covered the first two years of the Khmer Republic (1970-1972), so they were important. Some show enthusiastic support for the Republic in Phnom Penh at the outset and the strong anti-Vietnamese sentiment that fueled it. Mabuchi and I covered the later period (1973-1975). Then there were well-documented photos from Ros Reasey of the aftermath of the Vietcong attack on the Japan Bridge in 1972, and aerial photography of refugees from the countryside coming to Kampong Thom in 1974. Finally, ETAPP co-director Sam Jackson III’s intimate photos of the American evacuation on 12 April 1975 completed the cycle. 4 We had no budget for big prints. For the first two exhibitions we got a good deal on panels, but for Naoki’s photos, we just mounted prints on sheets or on frames – not under the glass, but on top of it. I don’t like reflections. We did the same for the Khmer Republic exhibit. This hands-on approach seemed to work well. Audiences could see details and were not intimidated by sheets of glass.

The presentation might be basic, but Keiko’s preparation of the photo data is meticulous. Fifty-year-old negatives that have not been developed nor preserved in the best conditions require tweaking. Dust marks and scratches have to be removed manually. Auto settings do not work well. It takes time and patience. It can also be quite exciting. Examining enlarged negative images may reveal hitherto unnoticed details in the background that provide new information or a different perspective. For example, some street signs tell us that (now) Sihanouk Boulevard was Avenue 18 Mars 1970 (date of the Lon Nol-Sirik Matak coup d’état) in 1973, and the open space in front of the royal palace was Place de la République. These things I had forgotten, and you won’t find them on any current map. Another photo shows a devastated, post-bombardment landscape near Takhmau with only one lone figure walking down a road. It is an impressive image. But closer inspection reveals quite a few other people dug in and camouflaged [Fig. 6]. In another photo there is a pile of captured weapons with a soldier standing behind them, and a poster of a dancer. It says “Wel Come” (sic). The feeling of this picture is enhanced if you know that it’s a deserted country club and that American, Russian, and Chinese weapons are stacked on a heart-shaped dance floor; and even more so if you notice the skull-like shadow on the face of the soldier, a detail which, because of the backlighting, can only be brought out in the printing [Fig. 7].

Fig. 6: Devastated landscape after the American B52 carpet bombing. (Photo by Colin Grafton, 1973)

Fig. 7: Heart-shaped dancefloor, a repository for captured weapons. (Photo by Colin Grafton, 1974)

I regret that I failed to take notes at the time I took the photographs. I realize now the importance of accurate documentation and the fallibility of memory. An extreme case was my initial dating of the “dancers” photos to 1973, when they subsequently turned out to have been taken a year later, thus making them the last glimpse of the Royal Ballet before the fall of Phnom Penh. How could I have been a year off? It was a stressful time, and there were several reasons, but none of them acceptable. My main reason for dating them to 1973 was that on the same negative strip there were scenes from a trip to Neak Luong, which had been the scene of the infamous “minor bombing error” by US Air Forces in August 1973. I thought I had gone there with some friends a few months later. As the “dancers” photos came after this on the strip, I guessed they were from October or November 1973. Then one of the friends visited Phnom Penh and told me it must have been a year later because he had not arrived in Cambodia until June 1974. But there he was, in the photos! This placed the dancers’ photos and the dance performance much closer to the fall of Phnom Penh than I had imagined.

Our task in curating others’ photos would have been much easier if we’d had some documentation to help us. Although I must admit the “guessing game” was fun, we just didn’t want to make too many wrong guesses. Keiko and I may have developed an obsession with documentation, accuracy, and truth, and it has been exacerbated by the fact that many people don’t seem to care. Sometimes we think of a photo as art, but in history a photographic image must have documentation to ensure it does not perpetuate a lie.

Colin Grafton took the original photographs and wrote the documentation, and Keiko did the hard work of data preparation and display planning. This article expresses their shared views and observations. Colin’s photos, many of which were used in their exhibitions, can be found with extra and updated information at: https://colingrafton.wixsite.com/photography and https://colingrafton.wixsite.com/phnompenh1973

Colin Grafton travelled overland to Asia in 1969 and took photographs in Laos and Cambodia (1970-1975). He returned to Thailand as a volunteer in the Cambodian refugee camps in 1980. He and his wife Keiko Kitamura settled in Cambodia in 2014. Email: colingrafton@yahoo.com

Keiko Kitamura, who has extensive experience as a stage and light designer, has worked with Colin on exhibitions and projects at Bophana Center, Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, Meta House and the Institut Francais in Phnom Penh. From 2021-2022, she designed and produced the book “Dancers” based on photographs taken in 1974. Email: keikokit2@yahoo.co.jp