New Sovereignty amidst Vigilante Politics: Examining the Juridical Relationship between Far Right Hindu Nationalism and the State in India (2013-2023)

The last decade has seen an increasing number of attacks against Muslims, led mainly by members of vigilante outfits that ascribe to far-right Hindu nationalism. This essay tries to examine the inclination of agrarian youth in the north of India to seek avenues of socio-political mobility within vigilante outfits. We attribute this to the popularity of the current ruling regime: the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP), supported by its organisational arm the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh (RSS). In the agrarian north, such an appeal has been able to penetrate and replace older peasant solidarities with a broader appeal of Hindu brotherhood (bhychara). A sense of Hindu guardianship to recover from a feeling of victimhood has been assumed by local strongmen who are committed to violence against Muslims.

Interestingly enough, these outfits or sanghatans do not constitute a formal relationship with the BJP or the RSS. Rather, it is the commitment to far right politics and violence that draws in youth who aspire for a wider recognition within the formal political structures of the ruling BJP. In response, the state has increasingly accommodated far-right violence by way of a tacit nexus with vigilantism, demonstrated in the arbitrary implementation of law and order. This article shows how a state that is accommodative to vigilantism portends to shift the juridical character of sovereignty for Muslim victims of violence. Additionally, attacks against political opponents, journalists, and activists show how such a pattern can be extended to include new enemies or alleged threats.

Muslim lives between Muzaffarnagar 2013 and Nuh-Mewat 2023

During the general elections of 2014, the state of Uttar Pradesh played a decisive role in guaranteeing the victory of the BJP. The party swept 71 of the 80 parliamentary seats, a significant number that helped in crossing the half way mark of 272 seats. The election comprises millions of votes polled in 542 seats spread across a variegated electoral landscape of the Indian subcontinent. Although the elections of 2014 were fought on the promise of developmentalism and against alleged corruption of the incumbent Congress Party regime, there was an overt display of far-right nationalist tendencies in the BJP’s poll pitch. In Uttar Pradesh, the campaign was vitiated by the anti-Muslim riots of 2013 that swept through parts of the Western regions abutting the national capital Delhi. The violence, perpetuated by dominant peasant castes such as the Jats, led to the displacement of over 70,000 persons belonging to the Muslim community. The displaced continue to live in shanties on the margins of congested towns such as Shamli and Muzaffarnagar. Their pleas for justice and compensation have been met with strong disavowal and intimidation by far-right outfits. Such resistance is led by local Jat strongmen who in 2013-14, broke away from the secular appeals of peasant brotherhood to formally align with the electoral interests of the BJP. Now in 2023, these leaders are either elected to positions of power, such as the union minister Sanjeev Baliyan, or else they wield major local clout, as in the case of hereditary caste headman Rajinder Singh Malik. These leaders have been instrumental in ensuring that pleas for justice by those displaced during the 2013-14 riots are delayed and denied.

Fig. 1: Homes demolished in Nuh-Mewat after the outbreak of violence between the residents and supporters of vigilante groups. Photo courtesy of Akram Akhtar Choudhary, 2023

It is alleged by those responsible for the riots that Muslim claims to monetary compensation are motivated by malefice, whereby false statements given to claim compensation also include names of ‘innocent’ persons who have spent many years in jail. 1

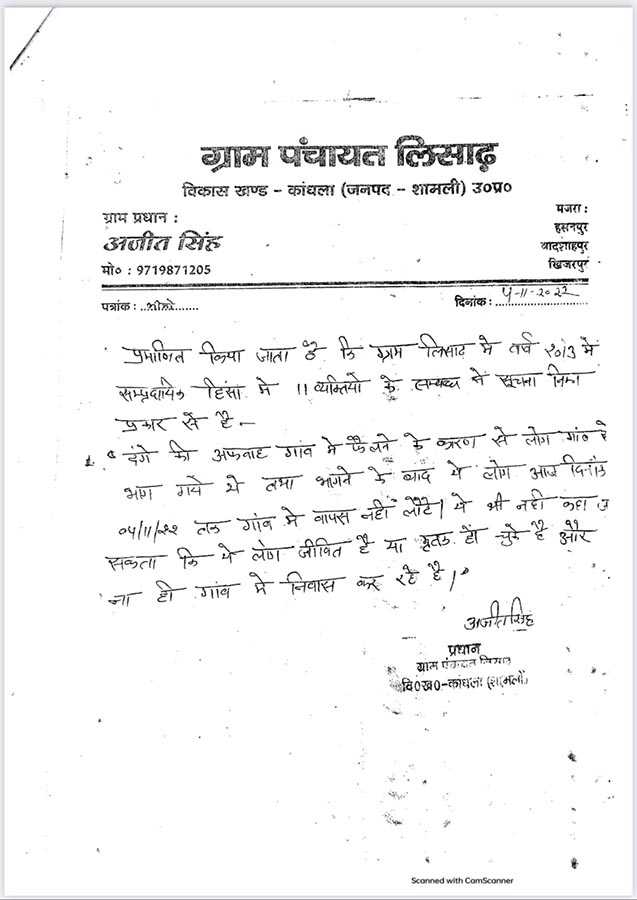

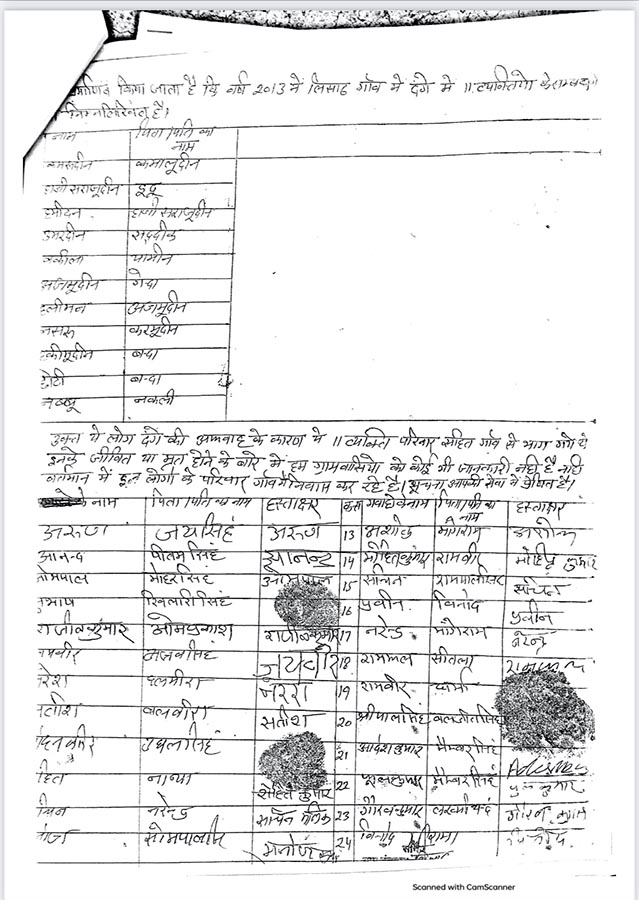

A rival embodiment of criminality is manufactured, wherein displaced Muslims are seen as the aggressors. Take for instance Right to Information Act 2005 queries that were filed by one of the authors (Akram Akhtar) to solicit responses regarding the delay in compensation. The responses reveal how a nexus between the accused and the administration developed to compromise surveys conducted in 2013 and again in 2023 to identify the number of displaced families, missing or dead. One example is Ajit Singh, who was the elected head of the riot-hit village in 2013 and continues to remain the elected head. India has a three-tier democratic system where the election of village heads is recognised by constitutional and legal sanction. In a recent letter signed and attested by Singh and the panchayat (village council) members, as part of the survey, it is stated that those being considered displaced had run away from the village in 2013 [Figs. 2-3]. Therefore, there were no grounds to connect their disappearance or those being considered ‘missing’ with the violence [Fig. 4]. The delays in ascertaining the list of displaced Muslims has confirmed a sense of Hindu victimhood, whereby the displaced are held responsible for disrupting inter-community brotherhood (bhychara). 2

Fig. 2: Letter signed by Ajit Singh and attested by members of the village stating that there is ambiguity over where the so-called displaced are, as they ran away from the village and never returned. It further states that it is therefore not possible to ascertain whether they are alive or dead. (Image courtesy of Afkar Foundation – Shamli)

Fig. 3: Right to Information Act Reponses showing signatures of members of the local panchayat attesting to the ambiguity over the so called displaced and missing persons. (Photo courtesy of Afkar Foundation - Shamli)

The more recent riots in August 2023 in Nuh-Mewat, located in the state of Haryana (adjacent to Delhi’s western and northern borders) offer a clearer articulation of how vigilantism and the state have institutionalised the criminalisation of Muslims under the garb of law enforcement. 3 In August 2023, a Hindu procession that annually visits a local temple in Muslim majority Nuh-Mewat in the state of Haryana, which shares its eastern and southern borders with Delhi, was infiltrated by masked men bearing swords, guns, and sticks. In the days running up to the procession, Bitu Bajrangi and Monu Manesar, leaders of the far-right outfit Bajrang Dal, constantly put out videos stating that the procession was a show of strength against the local Muslims of Mewat. 4 Attempts to intimidate Muslims in the region comes in the wake of a systemic online attack that targets Muslim-majority Mewat as a hotbed of fundamentalism. On the day of the procession, the visible presence of armed men in the procession evoked a reaction from the local population, whose sticks and stones were met with gunfire from anonymous persons in the mob. 5

Fig. 4: Displaced families frequently

visit the administrative offices in

pursuit of basic entitlements such

as water, sanitation, and electricity.

A day after the violence, the administration heeded to calls by vigilante outfits to assuage their feelings of hurt by levelling exaggerated allegations of violence against the residents of Nuh-Mewat. The police responded by commencing a brazen demolition of over 1000 homes belonging to the local Muslims in Nuh-Mewat. The residents were handed backdated notices of eviction for being in violation of building regulations, and their homes were now classified as encroachments. Though the demolitions attracted widespread condemnation by human rights groups, the high court took three days to take notice. In writing an unsparing order to halt the demolitions, the court stated that the exercise to demolish was done under the guise of protecting law and order but asked whether it was an act of ethnic cleansing. Naseem, one local activist who was instrumental in saving the lives of persons who were part of the Hindu procession, also had his home demolished [Fig. 1].

Agrarian north and the crystallisation of vigilantism

In the states of Haryana and Uttar Pradesh (UP), the rise of vigilantism builds upon or borrows from older forms of violence. It is a region that has been witness to decades of honour killings, conflicts over land ownership, and attacks on Muslims who constitute a sizeable share of the overall demography. Moreover, the lack of employment opportunities that have emerged out of an agrarian crisis has found expression in networks of organised crime that thrive on the illicit mining of sand, informal brick kilns, government contracts, and trade in illicit commodities. 6 Vigilante work is overseen by local strong men who profit from a criminalised economy and are able to provide economic stability and an expression for political ambition to the rural unemployed. It has drawn a vast number of youth into joining local far-right outfits who overlook contestations between caste groups.

An important issue that has been heavily politicised or has consistently determined the outcomes of vigilante is cow protection. The sacredness of the animal is pitted against Muslim butchers and cattle traders who, despite playing an important role in maintaining the land-livestock equilibrium, are portrayed as villainous cattle smugglers. From 2014 onwards, news reports drew attention to the growing number of lynchings that were being committed against Muslim cattle dealers on the suspicion of carrying beef. Routes connecting important cattle markets to agrarian spaces began to be controlled by vigilante outfits who chased and waylaid trucks carrying cattle. The far-right media ensured that instances of deaths and injuries caused to Muslim cattle dealers was used to defend the accused and hail the latter as saviours. The vilification of cattle dealers and therefore the whole Muslim community followed in the tracks of the Muzaffarnagar riots, where the victims were first demonised and later criminalised by law enforcement.

A second important issue has been that of love jihad, or the alleged elopement of Hindu women with Muslim men. In the agrarian north, the declining levels of employment have created a major obstacle for marriage for surplus men, who are viewed as undesirable in a marriage market that puts a high price on those with government jobs. Forced bachelorhood is rescued by way of self-professed celibacy. This is articulated by way of vigilantes, who stand guard against love Jihad.

Law and order as an obfuscation of vigilante violence

How does a legal architecture reimagine itself in relation to vigilantism, especially in the context of BJP-ruled states in the north, where vigilante networks have been an active force for at least a decade? The period after the Muzaffarnagar riots of 2013 showed how pleas for justice by the displaced were turned into a conspiracy that escalated feelings of Hindu victimhood. Over the years, the ability of far-right outfits to influence law enforcement has also developed into a strategy to enact anti-Muslim legislation. Many of the BJP-ruled states have strengthened the laws against cow slaughter that were in place for decades. In UP, soon after Yogi Adityanath came to power, it was decided to make such laws more punitive. The earlier anti-cow slaughter legislation was amended and tethered to the National Security Act (NSA). 7 In this way, a person accused of cattle smuggling is typically viewed as an enemy of the state/nation. The NSA permits prolonged periods of confinement without recourse to redressal. The post-2013 period has also shown how each year, cases that were filed against the accused rioters were closed for want of evidence. The working of law and order in such cases undergirds and reinforces local forms of vigilantism.

In Haryana, the situation is slightly more direct and brazen: cattle vigilantes are now incorporated into a task force that works with the police in apprehending alleged cattle smugglers. 8 This also explains the reason for the meteoric rise of persons like Monu Manesar, accused of inciting the violence in Nuh-Mewat. Manesar has been a long-term member of the cattle task force and is a popular Youtuber, who uses the online platform to post videos of waylaying and nabbing alleged cattle smugglers. In February 2023, two Muslim men were abducted, tortured, and burnt, allegedly by Manesar and his men. 9 Yet, the administration in Haryana has been slow to respond to these charges or to acknowledge Manesar’s involvement in inciting the recent violence in Nuh. Manesar is affiliated with the pan-Indian Bajrang Dal and therefore attracts a great deal of coverage on social media and within right-leaning political circles. Men like Manesar ignite aspirations that create pockets of majoritarian populism across the agrarian north. These are groups who are not necessarily affiliated with pan-Indian outfits but still contribute to the general movement, whose commitment to violence and hate has a bearing on the legal framework.

While vigilantism can influence how the law is implemented, it meets with juridical ambiguity when the absence of law necessitates – or is perceived to necessitate – a response to a manufactured Islamic threat. In such instances, the government either amends an existing law – as in the case of cow slaughter – or it manufactures a new law. Anti-conversion laws, for instance, came into being as an outcome of anxiety espoused by surplus men in the north about the alleged elopement of Hindu women with Muslim men. Soon after the enactment of the law, its implementation involved the active role of vigilante groups, who violently intervened to stop interfaith alliances. While the law purports to deal with ‘forced’ marriage, it is vigilante men who, with the help of the police, intimidate and frame false cases against Muslim men in consensual relationships with Hindu women. The pervasive role of these groups has been brought to light when Hindu women who consented to marry Muslim men refused to testify that the marriage was a case of forced conversion.

What about extra-judicial killings?

In 2017, when Yogi Adityanath assumed office, he announced a policy to clean up crime and create a safe haven for business to flourish. Since then, over 10,000 gun fights targeting mostly Muslims and lower-caste men have taken place. In police reports filed after an alleged gun fight, the introductory lines often claim that the police received a tip from an informer, after which the authorities swung into action and engaged the dreaded criminal. While the alibi of the police informer is not specific to the state of UP, there appears a close interlinkage between anonymous tips, vigilantes, and the selective use of police force against Muslims. The investigations that follow – since gun fights have to be investigated as per supreme court rulings and criminal procedure – conform to a construction of a crime scene as indicated in the (highly suspect) initial incident report. Evident signs of torture in the postmortem report and gunpowder signs indicating close-range fire are subsumed under the claim of self-defence.

At best, civil society groups have limited themselves to only questioning police claims of self-defence, but the basic plea remains to inquire into whether police procedure was followed during a gun fight. 10 However, since the chain of events is neatly constructed bearing in mind the demands of legal procedure and human rights conventions, the police are able to justify the use of excessive force in the name of self-defence. This helps the state defend itself on the grounds of protecting ‘law and order’ or working within the confines of known procedural conventions.

With a ready stable of informers available, the possibility of further violence against victim families cannot be ruled out. Take the case of Meena and Mustakeem. Their son Waseem was killed in an alleged encounter in 2017, and their son Mukeem was killed in judicial custody in 2021. 11 Soon after Waseem’s death, Meena was framed under the Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances Act, while Mustakeem has been framed in over 12 criminal cases since 2017. Despite criminalisation being used against them as an intimidation strategy, the family recently filed a writ in the supreme court. Their plea was represented by the noted lawyer and former union minister Kapil Sibal. The writ comes in the wake of the brazen demolition of Muslim homes in UP and instances where undertrials such as former parliamentarian Ateek Ahmed have been shot dead in broad daylight, while in police custody and in full view of the media.

Local sovereigns and the universal claims to citizenship

Monu Manesar, mentioned earlier, offers an example of how far-right populist politics can propel one from a local Hindu sovereign into a pan-Indian Dharam rakshak (“protector of faith”). And yet, Manesar is only one of the many local leaders across north India who command a social media presence and enjoy a cosy relationship with law enforcement.

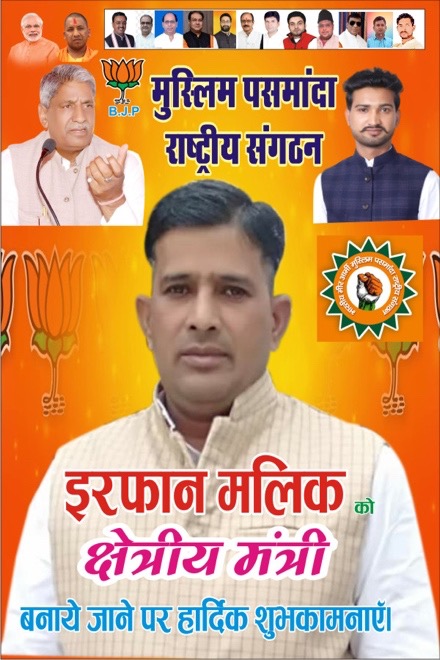

Fig. 5: Image showing greetings to Irfan Malik on joining the Muslim Pasmanda Rashtriya Sanghatan, a BJP initiative to reach out to “backward caste” Muslims Image courtesy Afkar Foundation – Shamli, 2023).

This also brings us to a final question: What consequences does such a state-vigilante nexus have for the universal questions of sovereignty? . The daily attacks on Muslims have acquired a juridical character of impunity that poses a universal threat not just to persecuted groups but also social groups and movements that are critical of the government’s pro-capital developmental outlook. An overwhelming climate of fear and intimidation is obscured by the government’s tokenistic claims of ‘pro-poor’ policies. A broad national consensus is therefore pitted against naysayers and critiques of the government, often by showing how Muslims, who many claim are persecuted, are joining the BJP in large numbers. This is not untrue, as is seen in the growing popularity of the Muslim Rashtriya Manch, the pan-Indian Muslim outfit of the BJP. The outfit has drawn numerous Muslim youth and leaders into the BJP fold [Fig. 5]. An emphasis on broadcasting images that show Muslim leaders wearing skull caps and sharing a stage with BJP’s top brass is constantly beamed across social media, posters, and pamphlets. While this serves to communicate an inclusive face of the current regime, it also reproduces the stereotype of the pro-development Muslim. The latter is one who supports and endorses ‘development’ and ‘progress’ as a departure from the criminalised stereotype of Muslims who continue to feed into fears (e.g., love Jihad, cattle smuggling, fundamentalism) and anxieties of Hindu victimhood. 12

Vishal Singh Deo is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Manipal Centre for Humanities and Philosophy. He specialises on political economy in the agrarian north as a way to examine contemporary majoritarianism.

Akram Akhtar Choudhary is a human rights lawyer based in Shamli (Uttar Pradesh). He is interested in examining the rise of mob violence in contemporary India.