The Memorycide of Babin Yar

I grew up behind the iron curtain in the 1980s. In Bulgaria, we learned at school that our freedom should never be taken for granted. Thousands of Russian soldiers died fighting for our right to be free. We were sworn as pioneers at the monuments commemorating their sacrifice. Our lives were organised around celebrations and manifestations attesting our deep gratitude for the Russian heroes. At the start of each school year, we brought flowers to the Monument of Aliosha. Yes, we referred to these heroes, cast in bronze according to the canons of Socialist Realism, by their first names. They were not a token of anonymous and distant memory; their bodies and armour stood guard of our daily lives. We identified with their valour and heroism. Ideology and sculpture went hand in hand. The remembrance of the Second World War was kept alive by constant reminders of the battlefields on which the Russian soldiers lost their lives for our liberation. Books, films, posters, all told countless personal stories of idealistic young men and women who perished in the name of Communism.

The intensity of these images is so powerful that even today I can visualize not so much the imposing monumentality of their carefully sculptured bodies but the determination on their faces while dying being shot by the Nazi enemy.

Pioneers greet each other by raising their right hand to their face and saying “Vinagi gotov” (“Always ready”). Ready for what? To die for the motherland? To serve the Communist party? To fight for freedom? I never really understood the essence of my pledge but I was proud to profess it. It gave me a sense of belonging. I was part of a wider fraternal brotherhood in which everyone would readily sacrifice their lives for freedom

Fig. 2: A large banner in the centre of Kyiv (Photo from the author’s personal collection, 2017).

My peers in Ukraine would have been raised with the same ideological narrative. Now they die fighting for their country. Their enemy is not the Nazi villain portrayed by Mosfilm.1 It is the very essence of the absurd, concocted story, carefully crafted and narrated by Mosfilm. They are fighting the Russian soldier. The memory of the Second World War has been reappropriated by the Russian propaganda machine as a powerful credo used as a weapon of war. The memory of the mass killings and destruction has been transformed into the killing of memory itself.

Над Бабьим Яром памятников нет.

Крутой обрыв, как грубое надгробье.

Мне страшно.

Мне сегодня столько лет,

как самому еврейскому народу. 2

No monument stands over Babi Yar.

A drop sheer as a crude gravestone.

I am afraid.

Today I am as old in years

as all the Jewish people. 3

What happened at Babin Yar?

Babin Yar (Babi/Babyn Yar in Russian), meaning “the ravine of the old woman,” is one of Europe’s largest mass graves and the scene of the biggest mass killing of the Holocaust. Within 48 hours on 29-30 September 1941, nearly 34,000 Jews were shot dead in a three-kilometre ravine situated in the outskirts of Ukraine’s capital Kyiv. Before the German invasion in September 1941, some 160,000 Jews resided in the city and constituted approximately 20 percent of its population. By the time the Germans occupied Kyiv, about 60,000 Jews remained. The majority of those who stayed behind included women, children, and the elderly; most of them were ill, malnourished, and unable to flee.

In early September 1941, two large explosions and fires shattered the city and destroyed the German headquarters. Many German soldiers and officials were killed in the engulfing flames. Although the explosions were caused by mines left by retreating Soviet soldiers, the attacks were framed as a pretext to murder the Jews who still remained in Kyiv. All Jews were requested to collect their belongings and head – at gunpoint – towards the outskirts of the city, genuinely believing that they were about to be evacuated. Once at Babin Yar, the victims were forced to take off their clothes and walk into the ravine, where they were subsequently shot by special killing squads. Those who survived the gunfire were buried alive. The walls of the ravine were blown up with dynamite. SS men searched and looted the belongings of the murdered Jews in early October 1941.

By the end of 1943, another 150,000 victims – including Jews, Ukrainian civilians, Roma, Russian prisoners of war, and physically and mentally disabled people from a nearby psychiatric hospital – were murdered by the Nazis and buried at Babin Yar. Near the end of the Second World War, the German soldiers forced Soviet prisoners to exhume the remains of the dead and to destroy the evidence of the killings. Some bodies were smothered with gasoline and burnt, after which a thin layer of earth was shovelled over them. The site was bulldozed to cover up the war crimes.

Even by the 1950s, Babin Yar was not recognized by the Soviet Union as a site of mass murder. Any attempts to erect a monument commemorating the thousands of victims remained futile, shrouded in the local population’s antisemitic sentiments following the pogrom against the Jews of Kyiv that broke out in September 1945.

The targeted policy of forgetting and destroying the memory of the mass executions at Babin Yar even resulted in the physical obliteration of all material traces and human remains that could be found on the site. In 1952, the local city council decided to fill the edges of the Babin Yar ravine with industrial waste. The geology of the site and its proximity to the city made it an ideal place for the disposal of brick residues from adjacent factories. The bricks were used for the construction of post-war socialist Kyiv. In the following years, Kyiv would become one of the largest cities of the Soviet Union with a population reaching 2.6 million people by 1989, surpassed only by Moscow and Leningrad (St. Petersburg).

On 13 March 1961 a dam collapsed at the industrial waste site built at the Babin Yar ravine. In the subsequent flooding, 145 civilians died in several residential areas of Kyiv. Parts of the city were cut off, and the military had to use boats and army vehicles to rescue the survivors and provide food supplies. All information about the tragedy remained classified under the Soviet authorities.

The mass killings of Jews and the flooding disaster continued to be largely unknown when, later in 1961, the Russian poet Evgenii Evtushenko 4 (1933-2017) published the poem Babi Yar, which turned the toponym into a synonym for genocide. The elegy was a form of protest against the Soviet authorities’ refusal to remember all victims. Its opening line – “No monument stands over Babi Yar” – encapsulated the decade-old painful memory of the massacres and the total absence of a commemorative marker. At the same time, the poem vehemently denounced the antisemitism that had spread throughout the Soviet Union during the post-war period:

I am

each old man here shot dead.

I am

every child here shot dead.

Nothing in me

shall ever forget!

The 'Internationale,’ 5

let it thunder

when the last antisemite on earth

is buried for ever.

The sentiments resonated with many intellectuals across Russia and beyond. Dmitri Shostakovich's Thirteenth Symphony (subtitled Babi Yar) 6 is based on Evtushenko’s poem.

Following much deliberation, several artistic competitions were initiated after 1965 to erect a monument in memory of all Soviet heroes who died defending the motherland. The Russian word for a memorial (pamiatnik) derives from the word for memory (pamiat’). However, in the case of Babin Yar, the memory itself is being obliterated, and the term acquires the connotation of memorycide, the deliberate destruction of all traces of the minorities who lost their lives in 1941. The envisaged monument was in line with the Soviet regime’s agenda: the attempted eradication of the living memory of Ukraine. The suffering at Babin Yar was caused not only by the killings and lootings of SS soldiers but also by local Nazi collaborators such as militias and civilians.

A tribute to Soviet soldiers featuring their strong athletic bodies was finally built in July 1976. Its monumental scale represented the alternative narrative of heroism and did not portray the thousands of weak and starving women and children who were massacred at Babin Yar throughout the 1940s. The commemorative text referred to the thousands of civilian victims without indicating that the vast majority of them were actually Jewish and that others belonged to the Roma minority. The official narrative stressed that the atrocities at Babin Yar were committed against the Soviet people in general and against the citizens of Kyiv in particular.

My visit to Babin Yar in 1985

I come from Bulgaria, a close ally and satellite state of the USSR. When I was growing up in the 1980s, we were encouraged to have pen friends from across the Soviet Union. The friendship between the two nations played a major role in the ideology of the communist regime. We started learning Russian as a second language at the age of ten. Our knowledge about the fraternal peoples of the USSR was carefully crafted by communist propaganda. On Fridays, Bulgarian state television relentlessly broadcasted Russian films about the Second World War. The heroic exploits of Russian soldiers, their courageous endurance, and the victory over Nazi Germany were exemplary. In the childhood imagination of my generation, the benevolent bravery of the Russian heroes was beyond a shadow of a doubt. The war monuments commemorating their valour were adorning the envelopes of our Soviet pen friends. We were receiving postcards of their cities with selected war memorials that were potent reminders of the great sacrifice of all Russians in the Second World War. Twenty-seven million people lost their lives.

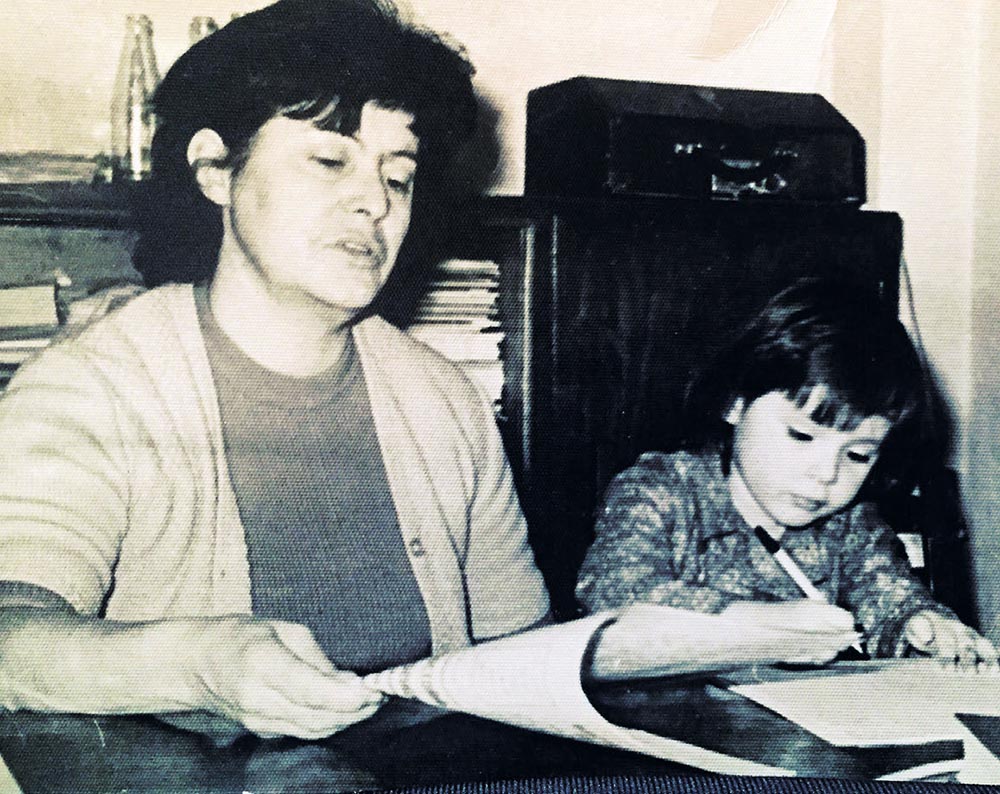

Fig. 3: My visit to Babin Yar in 1985. From left to right: my pen friend’s mother, my grandmother, me, our Jewish fellow traveller, June 1985 (Photo from the author’s personal collection).

My first pen friend was from Kyiv. As part of my communist upbringing, my grandmother, who was a journalist working for the local newspaper Dunavska Pravda, 7 took me on a trip to Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia in 1985. Such organized tours were closely controlled by the state, and the itinerary was in accordance with party guidelines. Very few people could be “approved for travel” beyond the borders of Bulgaria at the time, and I was in a privileged position.

Fig. 4: With my grandmother at the editor's office of Dunavska Pravda, 2 Feb 1978 (Photo from the author’s personal collection).

Kyiv was the first stop after our three-day train journey across Romania and Moldova. The city was dazzling with lights; the hustle and bustle of its wide avenues were overwhelming. We stayed only for two days but I vividly remember the glistening golden domes of Kyiv’s orthodox cathedrals and the city’s verdant parks. Yet, the only place that we actually visited was Babin Yar. Unfortunately, my pen friend was staying over with family out of town, so I could not meet her. We were welcomed by her mother, who took us kindly on a trip to Babin Yar. The memorial site mattered to her.

An elderly Jewish lady from my home town was travelling with us. She had come to Kyiv to see Babin Yar. Although she did not have any direct family members who had perished in the mass killings, this was a personal pilgrimage with a deep significance for her. She was a Holocaust survivor.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Babin Yar was recognized as a site of genocide. That marked a break from the Soviet rhetoric of forgetting. The appropriation of the physical space for commemorative purposes has resulted in more than 30 smaller monuments erected by the minority groups who lost their lives at Babin Yar. Their striving for symbolic recognition is reflected by numerous (sometimes failed) initiatives and organized pilgrimages to this contested site. Yet, until present, there is still not a single unifying monument that reflects the historical vicissitudes of the 20th century. In turn, the site of Babin Yar has become the physical representation of memorycide, the proliferation of a victimized memory, in which the act of memory itself has been victimized.

Fig. 5: The Ukraine Independence Monument in the centre of Kyiv (Photo from the author’s personal collection, 2017).

In an interview for the Associated Press in 2007, Evgenii Evtushenko recollected his first visit to Babin Yar: “I was so shocked,” he said. “I was absolutely shocked when I saw it, that people didn’t keep a memory about it.” 8 It seems that the opening line of his epic poem from 1961 – “No monument stands over Babi Yar” – is still valid, perhaps now more than ever.

The War in Ukraine

On 1 March 2022, the site of Babin Yar was struck by Russian missiles and shells as part of the ongoing military invasion of Ukraine. The indiscriminate attack hit the Babin Yar Holocaust Memorial complex and resulted in the deaths of five people. However, the menorah monument and the newly built synagogue, one of Babin Yar's most iconic memorials, reportedly remained unscathed. The Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who is of Jewish descent and lost relatives in the Holocaust, defined the attack as being "beyond humanity." In the words of Zelensky, Russia is trying “to erase our history, our country and all of us.” 9

The murders and war atrocities perpetrated at Babin Yar continue more than 80 years after the initial killings of innocent and vulnerable civilians. The targeted Russian policy of forgetting is not aimed at double memorycide, the physical destruction of people and their memory. It has gained another inhumane dimension that goes beyond Soviet-conceived narratives of antisemitism. In a reverse memorycide, Putin is invoking the painful – and at the same time heroic – memory of de-Nazification to justify his violent acts of war against a sovereign country. Putin’s distortion of history and his acts of delusion aim to discredit the independent nation of Ukraine and the ongoing struggle for freedom of all Ukrainian people.

Fig. 6: Student demonstration in support of Ukraine, The Dam Square Amsterdam, 2 March 2022 (Photo by the author, 2022).

In a highly polarized world that is slowly coming to grips with the long pandemic, the falsification of history is not a new tactic. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has divided governments and institutions among its former allies and has challenged the longevity of fraternal friendships. By employing strategies of democide and genocide towards Ukrainian civilians, Putin has redefined the very essence of painful memory. Unfortunately, world leaders have failed to unite beyond the phrase “Slava Ukraini!" (“Glory to Ukraine!”), which has cost uncountable lives and the massive destruction of livelihoods.

The tranquillity of the Ukrainian capital that I’ve witnessed, its lavish green parks and avenues, have been transformed into a barren cityscape of war devastation. Continuous news coverage with live correspondence across Ukraine seems pervasive. Unlike the scarcity of reporting from 1941, and unlike the attempts of Nazi SS units to cover up war crimes, we do know exactly what is going in Kyiv in 2022. However, the inert logic of world conventions and peace pacts has proven utterly inefficient in solving the pressing issues of today’s war.

In 2007, Evgenii Evtushenko referred to his tribute to Babin Yar as “human rights poetry; the poetry which defends human conscience as the greatest spiritual value.” 10 It is perhaps high time to re-evaluate our ritualized commemorative practices and to give a prominent voice to our human conscience in support for Ukraine.

Elena Paskaleva is Assistant Professor in Critical Heritage studies at Leiden University. She teaches graduate courses on material culture, memory and commemoration in Europe and Asia. Dr. Paskaleva is also the coordinator of the Asian Heritages Cluster at the International Institute for Asian Studies. E-mail: elpask@gmail.com