A medical dynasty: the Badmayevs and the Trans-Siberian knowledge corridor

Tibetan medicine did not come to Europe directly from Tibet; it arrived via Russia, specifically from Transbaikalia, the region east of Lake Baikal. It was a family of Buryat doctors who transferred their knowledge of Tibetan medicine, as they practised it, to the West. In the late 1850s, they opened the first Tibetan pharmacy in Europe and their medical formulas are still being produced in Europe today.

Flying to Tschita

I am flying from Ulan-Ude (Buryatia) to Tschita. The aircraft is an antique. It has remnants of 1960s elegance, with graceful upholstery and wide seats. But there are neither seatbelts nor lifejackets, and apparently only one engine works. “Don’t be nervous”, a neighbour tells me, seeing the fear on my face. “If it flew to Ulan-Ude, it’ll manage to fly back.”

From Tschita, the administrative centre of Transbaikalia, I travel to Aginsk, a small town in what was formerly Agin-Buryat Autonomous Okrug. In 2008 it lost its autonomy, which continues to be a source of resentment for most Buryats. I catch a marshrutka (a shared taxi that follows a fixed route), and the driver invites me to sit upfront. He asks: “Do you like it here”? “Yes”, I answer honestly. “You’re crazy”, he shakes his head. “One doesn’t come here. One escapes from here”. But I am going to Aginsk for good reason: to understand how a certain family of Buryat doctors was so successful in bringing Tibetan medicine from Transbaikalia to Europe, where their medical formulas are still in use today. Who were they? What helped them achieve this unprecedented knowledge transfer? And what made Tibetan medicine, as they practised it, so special?

On the steppe

In Aginsk, on the main square, a row of busts stand as if ready to welcome guests. They are all famous Buryats. There is Gombozhab Tsybikov, whose photographs of Lhasa were the first of the Tibetan capital ever to be published (National Geographic Magazine, 1905), and also Tsyben Zhamsarano and Bazar Baradin, two Buryat scholars and politicians. Aginsk is as different from Tschita as can be. The latter used to be a restricted-access military city; it has a feeling of neglect and decay. Not far from here lies Nerchinsk, where Decembrists served their prison terms. Deportation to Siberia was the typical punishment for political disobedience, and so when travelling to this region where people were exiled to disappear, you feel as if you are heading nowhere, to the end of the world. But you would be wrong. As slender, charred trunks of blackened trees (the latest taiga wildfires ended only a few weeks earlier) give way to the steppe proper, new horizons open up in front of your eyes. Entering the epicentre of Buryat culture, you are immediately struck by its uniqueness.

I continue to the village of Uzon, where I encounter a little ‘fairy-tale’ house and its inhabitants – a retired couple and their relatives. Over a wooden fence, a lush garden caresses the eye with a full palette of colours. Back in the house, the table bows under plates of dumplings, tomatoes, bread, honey and preserves. Everything here is home-made, self-grown or collected from nature’s garden. The lady of the house has an endless collection of jars in her kitchen cupboards. But her and her husband’s collection of books is even bigger – piled high everywhere you look, seemingly growing out of the floorboards. The couple, Galsan Tsyrendorzhiev and his wife Tsyndyma, belong to the local intelligentsia. Born here and educated in the city, they returned to work at the school and in cultural institutions. They are descendants of the Badmayevs, doctors of Tibetan medicine (fig. 1).

The beginnings

The best known member of the Badmayev family is Piotr. Born in 1851 as Zhamsaran, he left his steppe homeland to go to school in Irkutsk. Later, he travelled to Saint Petersburg, where he entered the medical faculty. But the main reason for his going to the capital was to help his brother, who had already started the first Tibetan pharmacy in Europe. The brother, Aleksander (Buryat name Tsultim Badma), the first of the doctor dynasty, was a rather different sort of man. Back on the steppe he had been a monk in Aginski datsan, one of the main Buddhist monasteries in Transbaikalia. His medical skills brought him admiration from influential Russians, including Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, general governor of East Siberia. Aleksander, as the story goes, helped him fight off a typhus outbreak in a Russian military garrison.

... the need to return to nature and for the harmonious development of body and mind.

In recognition of this, in 1857 Aleksander was invited to Saint Petersburg to be introduced to the Tsar. Once there, he opened a clinic and started treating patients. Yet, Aleksander’s success overwhelmed him, and he did not even speak fluent Russian. His younger brother had fewer difficulties with transitioning into this new life. Following Aleksander, he adopted Orthodox Christianity and changed his name to Piotr Aleksandrovich (after Tsar Alexander II). Most importantly, he mastered the family’s Tibetan medicine, including the art of pulse diagnosis and medicine making. When Aleksander died in 1873, Piotr expanded his practice.

Famous medicine from Aginsk

In fact, Aleksander Badmayev was not the first Buryat doctor in the Russian capital. Interest in Tibetan medicine from Buryatia and Transbaikalia was evident in Russian scientific circles as early as the eighteenth century. Scholars such as Johann Georg Gmelin, Gottlieb Messerschmidt and Joseph Rehmann explored the eastern frontier of the empire and reported on their encounters with Buddhist monk-doctors.1 Buddhism, with Tibetan Medicine, had arrived in the region in the second half of the seventeenth century and the first monasteries were founded in the following century. The two main religious seats in Transbaikalia were Tsugol and Aginsk.2 Medicine taught there was based on theoretical foundations from the Chagpori college in Lhasa and Labrang monastery in northeast Tibet.

Yet theory and practice are two separate things and Buryat practitioners adapted the Tibetan pharmacopeia to local conditions. Local doctors inform me that 80 percent of medicinal ingredients used in Transbaikalia are from the immediate area. Original formulas from Tibet, so the Buryats tell me, had to be adapted to the climate, diet and specific metabolism of their local patients: they were thus patient-tailored or even culture-tailored. When these lands became part of Russia and Russians began to settle here, the newcomers had little choice but to rely on local medics. Nikolai Kirillov, a doctor and ethnographer, reported that there were fifty-two ‘European doctors’ in Transbaikalia but thousands of monk-doctors.3 The latter dominated not only in number but also in quality. Seen in this light, calling for doctors from Aginsk to aid epidemic-struck Russian garrisons seems completely understandable – proof of the medical helplessness of the colonizers and the medical efficacy of the colonized.

Knowledge of the achievements of Buryat doctors soon spread to cities in European Russia. Scholars brought records of their trips and material findings back to their universities. Rehmann, for example, purchased a whole portable pharmacy. This intricate souvenir contained several dozen medicines and masses of information. In order to explain the medical system behind it, a Buryat doctor named Tsultim Tseden was invited to Saint Petersburg. Unfortunately, he passed away without moving the project forward.4 But the appetite for medicine from Asia had been ignited.

Man of paradoxes

Piotr’s biography is better known than that of his older brother, but its evaluation is obscured by the multiplicity of his activities. He was not only a doctor but also an entrepreneur and diplomat, engaging in diplomatic, trade and intelligence missions in the Sino-Russian borderlands. Elsewhere, he lobbied to lead the Trans-Siberian railway project to Lanzhou in China. He had political nous, too, and informed the tsar about the coming fall of the Qing dynasty and the ensuing political vacuum from which Russia should benefit.

Piotr’s life presents various paradoxes. A devout Christian, he initiated construction of the Orthodox church in Aginsk, but also co-financed a Buddhist temple in Saint Petersburg – a unique project combining Tibetan and art nouveau influences, still a must-see in the city. He was a sworn royalist but did not blindly represent the interests of the state; for instance, he lobbied successfully for his fellow Buryats when Russian policies grew stricter, as in the 1880s when the government started dissolving the steppe duma, Buryat self-government bodies, or when it pushed for religious radical conversion policies.

Despite his many interests, Piotr was a titan in the field of medicine. In 1893 alone, he was carrying out between 40 and 100 visits per day, amounting to 17,000-20,000 each year.5 He produced medicines, engaged in passionate polemics about the scientific value of Tibetan medicine and published the first translation of the classic Tibetan medical treatise, The Four Tantras.6 Earlier attempts to translate this hermetic text had been futile, but with Piotr’s organizational talent it became possible. The task involved cooperation of several Buryat monks whom he had invited specially to the city. In the process, Piotr ‘cleaned’ the text of elements of religion or mysticism, which as he put it, obscured its true value. His goal was thus not a verbatim translation but one that secured for Tibetan medicine a legitimate place in the pantheon of sciences.

The next generation

The October Revolution brought Piotr’s career to an abrupt end. As a friend of the tsarist establishment, Piotr was arrested and he died in 1920. But in his broad shadow, his two nephews were building their own careers. The first was Nikolai (alias Osor), who tried to acclimate to the new political realities. He was a Red Army doctor and treated Maxim Gorky and other celebrities of the new communist era. He wanted to practice Tibetan medicine within the Soviet medical system. With official permission, he opened a clinic of ‘Eastern Medicine’, but the ‘Badmayev brand’ was too closely associated with the tsarist regime, and soon Nikolai found himself arrested on the fabricated charge of being a Japanese spy. He pleaded guilty and was executed.

Nikolai’s younger brother followed a different path. Włodzimierz (alias Zhamyan) escaped from Russia and sought refuge in Poland, establishing himself in Warsaw where he quickly gained popularity as a medic. He published books and journals (Tibetan Physician and Synthetic Medicine) and was doctor to two Polish presidents. He wrote about the dangers of technological progress, about the need to return to nature and for the harmonious development of body and mind. Włodzimierz tirelessly explained the principles of Tibetan medicine, stressing that it is a proactive medicine of health and not, as its Western counterpart, a reactive one of disease. Similar to the other Badmayevs, he was a natural ambassador of his culture.

Born on the steppe, Włodzimierz successfully changed country, religion and language, lived through two World Wars and three revolutions. He was a man of the world, travelling to treat patients across Europe.7 In photographs, we see him on holiday, during state events and at parties (he in a tuxedo and his wife in fox furs, they fit perfectly into high society of the interwar period). Włodzimierz continued his work after the war, running a practice in two cities, Warsaw and Krakow – all this at a time when private entrepreneurship was actively repressed by the communist authorities.8

Aginski Zhor

Włodzimierz ran a laboratory and produced medicines. These were all officially registered, with a name (derived from Tibetan) and a number. This was the project his uncles had started in Saint Petersburg; to systematize the formulas they brought to Europe, by ordering, numbering and translating them. Włodzimierz purchased some ingredients from abroad, including India, while others were grown locally. He was an effective networker, and his son recounted that even during the Second World War his father was importing medicinal resources from abroad.9

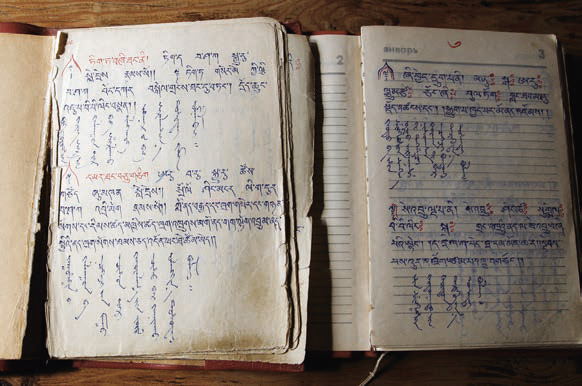

Włodzimierz prepared his medicines according to recipes from a particular book, the so-called Aginski Zhor (fig. 2). The zhor – or prescription book – as this genre of compendium is known, flourished among the Buryats. Local doctors compiled medical formulas with indications, dosage and modifications of contents. Aginski Zhor, from the monastery of Aginsk, contains 1197 individual recipes. Not all of them were used very often, but their number shows the ingenuity of local medics. Located in parkland surrounded by tall larches, Aginsk monastery is unique. Journeying through lands where radical communism swept away most sacral architecture from the landscape, you expect to encounter a cluster of new buildings erected ad hoc in the rural-Siberian style, mixed with Chinese influences. But Aginsk is different; its main buildings were spared from destruction. Today, the monastery has the serenity of truly old places, yet it appeals also to younger generations. Since 1993, after a forced break of over half a century, Tibetan medicine is being taught here again.

Fig. 2: Aginski Zhor, from the monastery of Aginsk, contains 1197 individual recipes. Since 1993, after a forced break of over half a century, Tibetan medicine is being taught here again.

Dmitrii Shakhanov, custodian of the library, showed me the monastic collection. Aginsk ran a large printing house in the past. It published, according to Dmitrii’s estimates, more titles than all the other Buryat monasteries together. Even today, after the years of Stalinist terror when many objects were destroyed or carried away to museums in Moscow and Leningrad, it still has one of the largest collections of Buddhist literature in Russia. The steppe climate is good for books; even old ones, opened once more after decades lying unread, look as if they have freshly left the press. Aginski Zhor is among them – in manuscript, xylographic edition and translation.

A time of brutality

Aginsk monastery witnessed some very dramatic times in the 1930s. In the first years after the revolution, Buryats tried to adapt to the new realities. The so-called Renovationist programme, led by Agvan Dorzhiev, another famous Buryat, introduced Western anatomy and diagnostics to Buryat medical colleges, while education was subject to state control. But after Stalin consolidated his power in 1928 there was no space for dialogue; anything that did not meet the prescribed norms and even slightly hinted at the past was sentenced to extermination. In 1936, Tibetan medicine was outlawed. Monasteries were closed and monks forced to disrobe. Many were executed.

Aginsk was shut down in 1937. It formally reopened in 1946, but its buildings housed military quarters, a tuberculosis sanatorium and drug addiction clinic. The monastic inventory was largely destroyed. “Soldiers threw books out of the windows”, a neighbour of the monastery told me. “Pages fluttered in the air and spread on the ground like snow.” People collected these fragments and hid them away. Many of these books are still secreted in people’s homes. Every now and then, an elderly Buryat brings back what she or he saved from destruction.

Nikolai Dugarov also has an important and sacred part of his family history stashed away in his home. I meet him at the National Museum (named after Gombojab Tsybikov, of National Geographic fame), he works at the ticket office. Nikolai studied art in Leningrad and returned to Aginsk because of his parents. Their history reveals much about the fate of the Buryats in the Soviet Union. But also about the fate of Tibetan medicine. “My father, Dambinima, was a monk-doctor. When the persecutions started, many monks were killed or ‘disappeared’. My father fled to Krasnoyarsk, together with khambo-lama Gomboev.10 One worked as a fireman, the other in a smelter”. So Nikolai starts his story. His mother was deported to Krasnoyarsk, a Stalinist centre in the gulag system. Mass deportations were a daily occurrence in Russia; Buryats, accused of harbouring nationalistic sentiments and carrying out espionage, were deported in their thousands. Many died because of the harsh working conditions. Many people never returned, but thankfully Nikolai’s parents did.

It required great stamina to survive. It also needed strength of character to practice medicine underground, which is what Nikolai’s father, now a layman, did when he got home. Yet he never instructed his son in this secret knowledge, as it was too dangerous. Nikolai did inherit his father’s prescription books though: his private zhor with condensed medical knowledge sharpened by years of (illegal) practice. The writing is all Tibetan or Mongolian, although in 1939 Buryats were forced to adopt Cyrillic script. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3: The prescription books left to Nikolai Dugarov by his father Dambinima, a monk-doctor, who survived the labour camps.

Broken ties: the journey continues

Did the family in Aginsk have any contact with Włodzimierz in Poland? “We knew that someone was living in the West”, the Badmayevs in Uzon tell me, “but any contact was too dangerous”. The contacts in Russia were broken too; Leningrad and Aginsk were thousands of miles apart. The damage wrought on the Badmayevs is shown most starkly in their genealogical tree, especially the branch who carried Tibetan medicine to the West. Traditionally, Buryat genealogical trees are male oriented. It is ironic that it was during a meeting with a woman that I learned about other Badmayevs. Born in 1931, Saran Bazarzhapova is Włodzimierz’s niece (fig. 4). Of her four uncles, one survived in Poland and one was executed, while the two others, who lived in Leningrad, died young or disappeared in unknown circumstances. Saran’s father stayed on the land but one night he was taken by the secret police and shot on espionage charges.

Fig. 4: Włodzimierz’s niece, Saran, the closest living relative of the Badmayev doctors, with her son Purbotsyren Baldorzhievich.

Włodzimierz died in Poland in 1961, but his formulas continued their journey. In 1959, Swiss entrepreneur Karl Lutz attended a lecture by Cyrill von Korvin-Krasinski, a Benedictine monk and expert on Tibetan medicine. The topic fascinated him and so Lutz decided to study Tibetan medicine, seeing in it a chance to revolutionize the European pharmaceutical market. Thus, Korwin Krasinski, a former patient of Włodzimierz, turned Lutz’s attention to the medical formulas of the Buryat doctor. Lutz wanted to rescue them from behind the Iron Curtain; the Polish authorities were not interested in continuing their production, but he feared that they would not like losing control over this unique heritage. Finally, in 1965, Włodzimierz’s son, Piotr, brought the Badmayev formulas to Zürich where Lutz began testing them. The company he founded, named after the Badmayev family, continues to produce them today.

The Trans-Siberian knowledge corridor

What was necessary for the Trans-Siberian knowledge corridor to function? It needed pioneers, daring spirits who did not shy away from publicity, who felt the spirit of the time and grasped possibilities. It required a ground ready to accept their knowledge. It also needed the flexibility of the Tibetan medical system, able to adapt to new circumstances. And it had to have teamwork. Western history books tend to highlight individual achievements, but the transfer of Tibetan medicine was a community success. The Badmayevs were in constant exchange with their fellow Buryats – monks in Aginsk and relatives on the steppe, who supplied them with knowledge and materia medica. This stopped during the years of the Great Terror and many people who built this history remain obscured. Their stories still need to be told.

Today, even for tourists exploring Buryatia, Aginsk is too remote to visit. Geopolitics have consigned it to a part of the country that can be entered only with a special visa; it is too far away from the centre for the authorities to leave access unrestricted. This makes it even more unusual; here Buryats speak Buryat (not always the case in Buryatia), the cult of high education, personified by people like Tsybikov or Zhamsarano, is alive and well, and the elite character of the place is highlighted not only by people’s stories that Chinggis Khan ‘was from here’, but also by the fact that almost everyone is somehow related – in a distant line – to one of the prominent figures in the monuments on the main square. The relatives of the Badmayevs from Uzon plan to erect a new monument – to Piotr Badmayev. The opening will take place on 17 July 2020 during the International Buryat Festival Altargana.

Emilia Roza Sulek, University of Zürich. emisulek@yahoo.com