Madness, Medicine, and Empire: Rethinking Colonial Psychiatry in Asia through Hong Kong

What if colonial governments presented themselves not through overt repression, but through promises of care and rehabilitation? This question first struck me when I began researching post-war Hong Kong. At first glance, Hong Kong may appear peripheral in the global history of psychiatry – a small, bustling city shaped by Cold War politics and British colonialism. But Hong Kong was deeply entangled in broader regional and imperial transformations, including urbanization, developmentalism, and decolonization. By focusing on this site, I explore questions that resonate across colonial and post-colonial Asia: How was psychiatry adapted to colonial and decolonial contexts? How did it intersect with local knowledge systems such as traditional Chinese medicine?

My research focuses on the transformation of colonial psychiatry in Hong Kong from the 1940s to the 1980s. Drawing on hundreds of patient case files and government records from local archives, I examine how psychological knowledge became central to welfare and legal reforms in the age of decolonization.

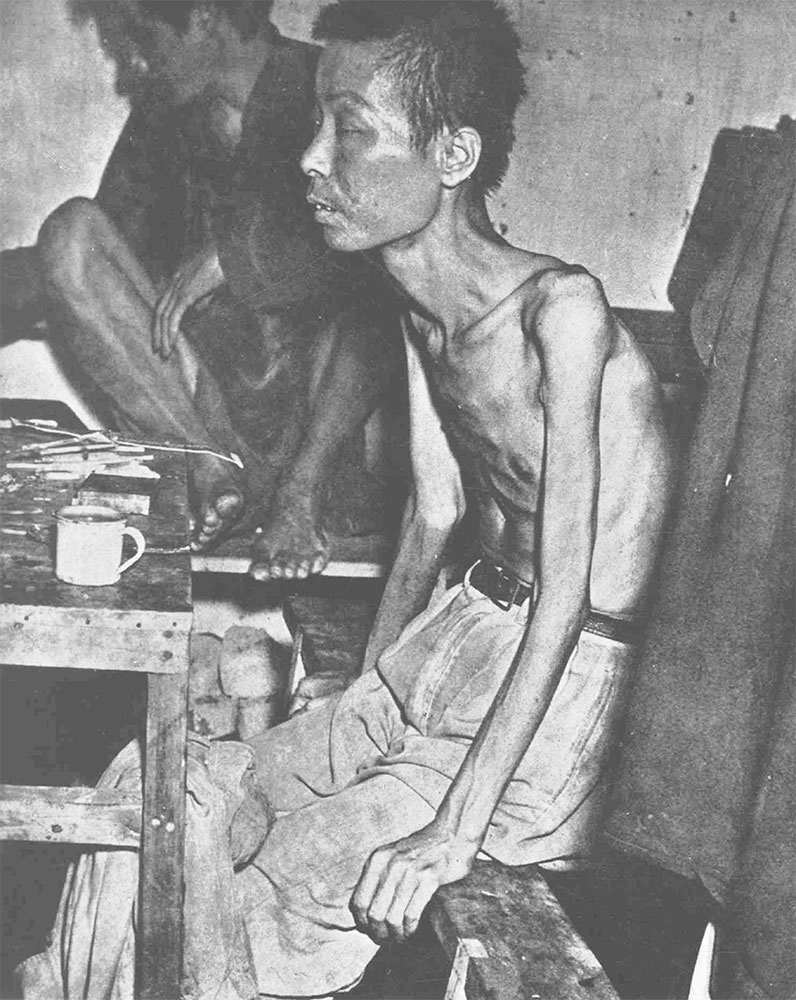

One of the clearest examples is the colonial government’s campaign against heroin addiction. If opium symbolized the height of British colonialism, then addiction treatment marked the empire’s decline. Pressured by the United States, colonial and postcolonial states across Asia were compelled to ban opium. Heroin quickly filled the gap. Beginning in 1959, Hong Kong – like many places in Southeast Asia – declared a “war on drugs.” Addicts were sent to rehabilitation camps and psychiatric hospitals. American medical experts were invited to oversee experimental treatment programs. Methadone maintenance, then a controversial practice in the US, was trialed in Hong Kong through randomized clinical experiments, turning the city into a laboratory for international drug policy [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1: The image of a “typical” addict from The Problem of Narcotic Drugs in Hong Kong, 1965. (Photo: author’s collection)

These efforts were widely promoted as a model of modern addiction treatment. But a closer reading of the archives reveals a more complicated picture. Patients frequently relapsed, treatment centers struggled with violence and overcrowding, and staff found themselves caught between ideals of care and the realities of control. The goal was not simply to cure addiction but to reshape addicts into moral, productive citizens – able to work, conform, and reintegrate into society. These institutions blurred the line between welfare and discipline, highlighting the uneasy role of medicine in the final decades of colonial rule.

Alongside the expansion of psychiatry, another story unfolded – not in official reports, but in newspapers, street-level pharmacies, and the clinics of traditional healers. During this period, the diagnosis of “neurasthenia” – once popular in 19th-century Euro-American psychiatry – found a second life in Hong Kong. Though Western-trained psychiatrists had largely abandoned the term by the 1950s, it remained widely used by Chinese medicine practitioners and patients themselves. Neurasthenia, with its broad symptoms of fatigue, irritability, and bodily weakness, offered a culturally familiar way to express emotional distress without the stigma of mental illness.

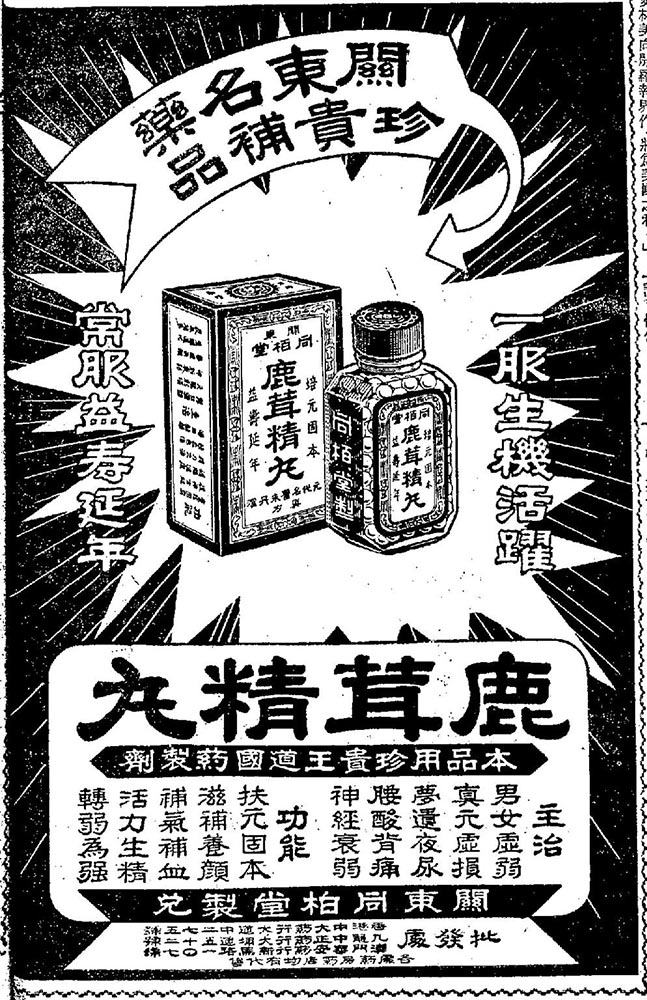

My second strand of research explores how neurasthenia was commercialized in postwar Hong Kong [Fig. 2]. Advertisements for proprietary medicines promised to “restore nerves,” while popular self-help manuals framed the condition using a mix of Chinese medical idioms and biomedical vocabulary. Neurasthenia was described as a disease of modern life, brought on by fast-paced living, crowded housing, and social pressures. In this context, traditional Chinese medicine practitioners positioned themselves as experts in mental health, even as official psychiatry viewed them as unscientific or obsolete.

Fig. 2: Deer antler pill that claimed to treat neurasthenia, Wah Kiu Yat Po 華僑日報, 1 February 1960. (Photo: author’s collection)

These dynamics were not unique to Hong Kong. Across Asia, neurasthenia has persisted as a common diagnosis – especially in Taiwan, mainland China, and among overseas Chinese communities – long after it disappeared from Western psychiatric classifications. Its continued use raises broader questions about how mental illness is understood in non-Western contexts: how symptoms are framed, which institutions people trust, and how medical categories travel and adapt across cultural and political borders.

In this sense, Hong Kong offers a useful lens to revisit larger themes in the study of Asia: colonial legacies, medical pluralism, and the politics of health. It sits at a crossroads between Chinese cultural traditions and British administrative structures, between regional migration and global medicine. The city’s psychiatric history is not only shaped by local conditions, but also by the Cold War, developmentalism, and decolonization. Its story reflects how global ideas of mental health were interpreted, contested, and reconfigured in specific Asian contexts.

As I continue this research, I find myself returning to questions that extend beyond the archive. How do people navigate systems that claim to heal, yet also surveil? And how might the history of psychiatry help us understand the present – not only in Hong Kong, but in other postcolonial societies still grappling with the inherited infrastructures of empire? These histories of medicine and madness, I believe, are not only about the past – they offer insights into the current global mental health crisis.

Dr Kelvin Chan is Research Associate at the Hong Kong History Centre, University of Bristol. Email: kelvin.chan@bristol.ac.uk