The kantha or, as it is increasingly referred to as the nakshi kantha, is an important aspect of Bengali women’s domestic arts and crafts. Kanthas are made in most parts of Bangladesh as well as in West Bengal. The kantha has taken many forms: from simple quilts made at home for personal, domestic, or ritual use to elaborate story-telling wall hangings for public view. Kanthas are used for traditional garments, such as saris and shawls, as well as for Western garments, such as jackets and stoles. Made initially from old garments like cotton saris, lungis, and dhotis, the kantha is now made with new cloth, either cotton or silk.

With these transformations, the kantha can now be found worldwide, not only in museums, but in catalogues and shops, in drawing rooms and boardrooms, and worn by fashion models on runways.

How kanthas are made

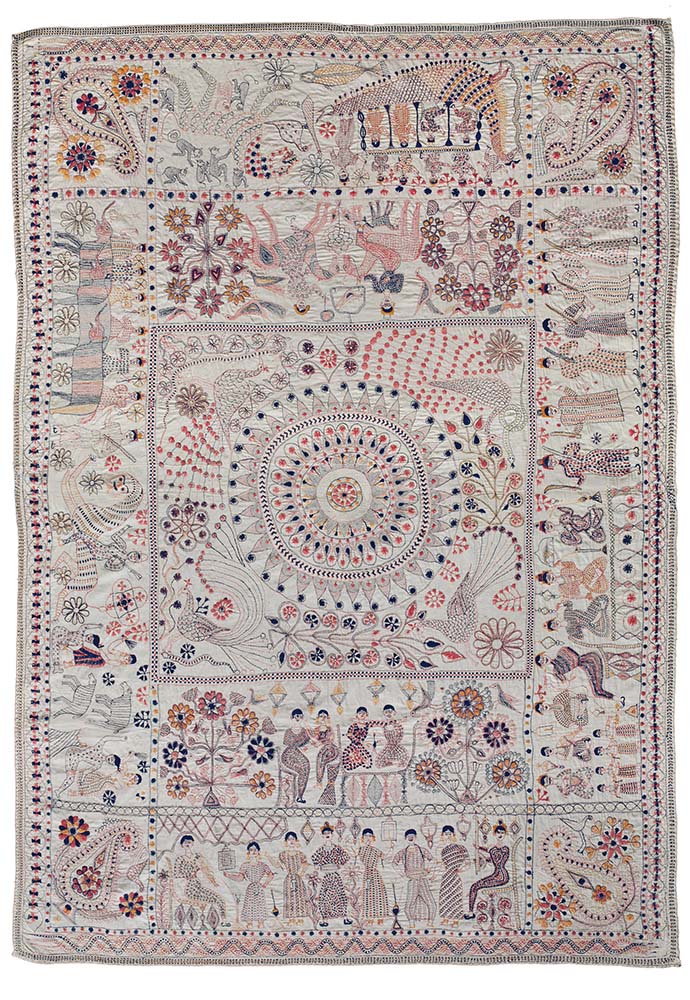

Traditionally, layers of old saris, lungis, or dhotis were put together and reconstituted into objects of functional, ritual, or ceremonial use. Borders and motifs were embroidered in variations of the running stitch with coloured thread, traditionally drawn from the borders of old saris. The empty spaces were stitched with white yarn to create a ripple effect [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1: Stitches between motifs create a ripple effect, characteristic of the traditional kantha. Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection, 2009, 2009-250-2 detail. Collection Page: https://bit.ly/3xogAgN

At least five to seven saris were needed to make a full-length kantha – the number of layers depending on the thickness required. Ceremonial kanthas, such as those spread for guests and to accommodate the bride or groom would have fewer layers and finer embroidery. Thicker kanthas, to be used as winter quilts, would have more layers of cloth.

At the beginning of the process, women would spread layers of the cloth on the packed-earth ground of the courtyard. The edges would be pinned to the ground with thorns from date trees. The cloths would then be folded in and stitched. Long running stitches at intervals down the length of the cloth would be worked to keep the layers together. The kantha could then be folded and put away to be further worked and embroidered when convenient. Typically, a large lotus would be worked in the centre. Following this, corner motifs and then numerous other motifs or scenes would be added, depending on the time and artistic ability of the kantha artist. Some very fine 19th-century kanthas relate scenes from the story of Radha and Krishna. Decorative kanthas are stitched through the layers of cotton or through a surface layer of silk and lower layers of cotton. Embroidery yarn in the past was taken from the borders of saris and would be generally blue, red, or black.

Today, old saris are replaced by new cotton fabrics. As this material is normally thicker, two layers of cloth may be sufficient for a kantha. Most of the stitching and embroidery yarns today are purchased separately and are available in multiple colours. While cotton yarn is still in general use, nowadays bamboo, rayon, or silk floss threads are also used, especially for commercial kanthas.

In most Bengali families, small kanthas made of soft, old cloth, are used to wrap babies. Husbands or sons who leave home to work almost always carry with them a kantha made by their wives or mothers. The kantha symbolises the affection of the maker for the recipient and, being made of rags, is also believed to grant protection from the evil eye. Kanthas also form part of the dowry of brides in certain parts of Bangladesh and West Bengal.

Brief history

Quilts made of multiple layers of cloth are common all over the South Asian subcontinent. However, the kantha, with its running stitch embroidery, seems to have its roots in Bengal. Known sometimes as sujni – from the word for stitch or needle – it is also related in form to the suzanis of Central Asia.

The finest 19th-century kanthas come from the Jessore, Faridpur, and Khulna regions of Bangladesh, bordering what is now the State of West Bengal in India. Others come from Rajshahi and Kushtia, where they are generally thicker than the others. A kantha from Kushtia presented as a gift to the renowned poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), who lived in Shelaidaha between 1891 and 1901, is preserved in Santiniketan.

The early years of the twentieth century saw the rise of the swadeshi movement for independence from Britain. It also saw an interest in recovering the past traditions of Bengal. The Bengali educationist, writer, and folklorist Dinesh Chandra Sen (1866-1939) collected ballads and kanthas from the region – work in which he was aided by a young Jasimuddin (1903-1976), who would later write the poem Nakshi Kanthar Maath, translated as The Field of the Embroidered Quilt. The term nakshi kantha derives from this poem. The Bengali civil servant, folklorist and writer Gurusaday Dutta (1882-1941) collected different forms of folk art, including the kantha. It was also at this time that the art historian Stella Kramrisch (1896-1993) started collecting kanthas and writing about them.

The partition of India in 1947 led to many Hindu families leaving East Pakistan for India, taking with them kantha skills. At Santiniketan, in India, a special form of kantha was developed – along with batik and leather work – to provide work for women. Santiniketan kanthas, however, are worked with the herringbone stitch, which helps create large areas of colour. This kantha work is mainly used to embellish silk saris and is very different from the type of kantha made in Bangladesh.

In East Pakistan, growing cultural awareness against cultural domination by West Pakistan arose together with the Language Movement, especially after the police shooting on a peaceful procession demanding Bangla as a state language on 21st February 1952. This also helped promote the survival of the kantha craft in Bangladesh. The real revival of the kanthas started with the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, when artists such as Quamrul Hassan (1921-1988) and Zainul Abedin (1914-1976) initiated a resurgence of interest in traditional arts and crafts, including the kantha.

Kantha revival

In 1971, famine and food shortages ravaged the newly-born nation, and many women were widowed in the preceding war or separated from their families. In an attempt to rehabilitate destitute women, kantha-making was promoted as an economic activity, particularly in Jessore, Kushtia, Faridpur, and Rajshahi, parts of Bangladesh with strong kantha traditions. Karika, a handicrafts cooperative, was set up and helped promote kanthas by using its motifs and embroidery on household goods and garments. Karika was followed by Aarong – the outlet for the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) and then for the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) – and Kumudini, another NGO. However, the catalyst for the kantha revival was, strangely enough, the opening of the Pan Pacific Sonargaon Hotel in Dhaka, in 1981.

Fig. 2: Photographs of 19th-century kanthas such as this inspired Surayia Rahman to design a wall-hanging for the Sonargaon Hotel, Dhaka. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Stella Kramrisch Collection, 1994, 1994-148-684. Collection Page: https://bit.ly/3rRQbGS

Surayia Rahman (1932-2018), an artist who had earlier worked with the Women’s Voluntary Association, was invited by BRAC to design a kantha wall-hanging for the new hotel, based on photographs from the Stella Kramrisch Collection in the Philadelphia Museum of Art [fig.2]. BRAC, which had been working with kanthas and had produced a sample wall hanging, was, for various reasons, unable to embroider the large textile artwork for the hotel. As a result, Surayia Rahman’s design was embroidered by artisans at Kumudini. [Fig. 3].

Apart from Surayia Rahman, Razia Quadir also designed two pieces, one of them replicating different forms of the lotus motif down its length, the other a marriage scene using the basic running stitch. Razia Quadir’s kantha with the marriage scene and Suraiya Rahman’s wall hanging in the Sonargaon Hotel have influenced later kantha production in Bangladesh.

Surayia Rahman co-founded the Skill Development for Underprivileged Women (SDUW) organisation in 1982, in cooperation with a Canadian expatriate, Maureen Berlin. Rahman created elaborate story-telling designs for kantha wall-hangings. Her refined designs were often on silk rather than on recycled saris or cotton, and she used locally produced bamboo-processed threads. Embroiderers working for the organisation used a hoop to hold the fabric taut as they stitched the designs [Fig. 4], thus creating a distinction from the ripple effect in earlier kanthas, where the fabric was held by hand or stretched with a foot.

Fig. 4: Kantha embroidery in process, stitched with a hoop, Bangladesh. Photograph: Kantha Productions LLC and Anil Advani.

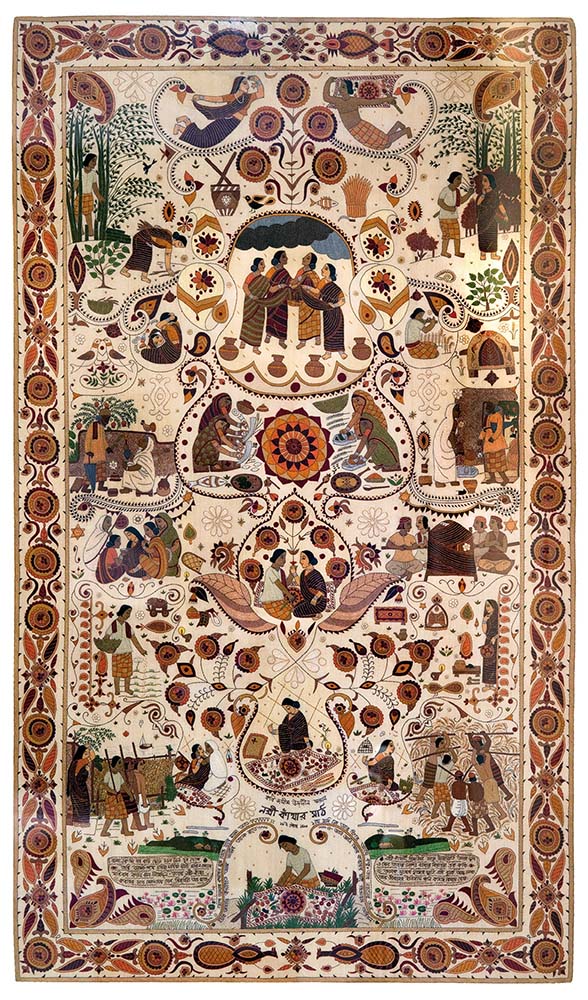

Rahman’s wall-hangings, created in cooperation with the women artisans who she trained, became known as “nakshi kantha tapestries.” Though kantha traditionalists protested that Rahman’s kantha wall-hangings were not true kanthas, Rahman persisted in creating this refined textile art in the kantha tradition. Following four years at SDUW, Rahman formed her own organisation, Arshi, to promote skill development, dignified work, and income generation for hundreds of women. A number of Rahman’s pieces are based on Jasimuddin’s poems, such as The Field of the Embroidered Quilt: Nakshi Kanthar Maath [Fig. 5].

Fig. 5: The Field of the Embroidered Quilt: Nakshi Kanthar Maath. “Nakshi Kantha Tapestry” by Surayia Rahman and artisans of Arshi. Bangladesh. Photo: Kantha Productions LLC and Anil Advani.

Movement of the revival to West Bengal

In Bangladesh, the kantha revival focused first on the traditional craft that could be used in contemporary ways; in West Bengal, India, the kantha was more commercialised from the outset. Santiniketan designs, for example, are to be found on inexpensive blouse pieces as well as on expensive silk saris. Bangladeshi saris using kantha embroidery are generally more muted. Often, it is only the body of the sari that is worked in the running stitch, creating the traditional ripples, with a simple weave-running stitch border and an anchal – or sari end – with a few traditional kantha motifs, such as the kalka or paisley.

Crafts Council of West Bengal has worked closely with kantha producers. Ruby Palchoudhuri, at present President Emeritus of Crafts Council of West Bengal, sent young designers to different museums to examine the different stitches used in kanthas. The Golden Jubilee celebration of the Crafts Council of West Bengal in 2018 focused on kanthas and kantha-makers. Titled “The Eye of the Needle: Kantha, the Quilt Embroidery of Bengal,” it exhibited antique pieces as well as contemporary ones.

Tens of thousands of artisans in West and East Bengal now make kanthas for income generation. Relatively few develop their own designs for their own use, but replicate popular designs, often designed by specialists. In West Bengal, for example, Farah Khan has been making high-end dupattas and saris using the type of kantha stitches used for the rural wedding piece designed by Razia Quadir for Hotel Sonargaon and popularised by Banchte Shekha, a Jessore-based NGO [Fig. 6].

Fig. 6: Farah Khan in a self-designed dupatta, with kantha-inspired embroid-ery. West Bengal, India. Photo: Hafiz Khan.

Artists are also exploring the kantha for inspiration. The Bangladeshi artist, Shah Abdus Shakoor (1947-), paints kantha stitches on his pictures based on Mymensingh ballads. The late Indian artist, Meera Mukherjee (1923-1998), drew upon the kantha for her embroidered pieces, called “stitched paintings,” whereby children made the drawings and kantha artisans did the embroidery.

Global movement of kanthas

Foreigners visiting Bangladesh and India – where antique pieces find purchasers – acquire traditional kanthas and newly worked kantha wall hangings to take home, raising an awareness of the fineness of the handwork of this region. Exhibitions of kanthas have been hosted in prestigious museums, such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Japanese collector Hiroko Iwatate has established the Iwatate Folk Textile Museum in Tokyo, which has a large collection of kanthas. Kantha quilts and kantha-embellished garments can be found on the internet, in shops selling handcraft, and in department stores in Bengal and around the world. As the kantha becomes appreciated worldwide, with more attention paid to sustainability, slow fashion, and folk arts, it also has the potential to inspire new generations of artists, craftspeople, and designers.

Niaz Zaman is the author of The Art of Kantha Embroidery, the first book-length study of the kantha. At present, she is Advisor, Department of English and Modern Languages, Independent University, Bangladesh. niaz@iub.edu.bd

Cathy Stevulak is a Canadian filmmaker and international programme consultant. Her interest in textiles and the advancement of artisan enterprise, particularly in South Asia, led her to direct and produce the award-winning film, THREADS. cathy@kanthathreads.com, www.kanthathreads.com

Works Cited

Balakrishnan, Rekha. “Meet the Army Wife Who Is Reviving Kantha While Empowering Hundreds of Women Artisans in West Bengal.” https://yourstory.com/herstory/2019/10/army-wife-woman-entrepreneur-kantha-revival. Accessed March 13, 2021.

“Nestled: Adip Dutta and Meera Mukherjee.” http://www.platform-mag.com/art/nestled-adip-dutta-and-meera-mukherjee.html. Accessed March 13, 2021.

Shakoor [Abdus Shakoor Shah]. Ballads and Paintings. Dhaka: Cosmos, 2009.

Zaman, Niaz. The Art of Kantha Embroidery. 3rd revised edition. Dhaka: UPL, 2012.

Zaman, Niaz and Cathy Stevulak. “The Refining of a Domestic Art.” Textile Society of America 2014 Biennial Symposium Proceedings: New Directions: Examining the Past, Creating the Future. Los Angeles, California, September 10-14, 2014