K–pop in Distance: An Uzbek Fan's Perspective

I clearly remember my first introduction to K-pop. My older sister and cousin always watched videos on a computer and giggled while discussing them. As a 12-year–old girl who wanted to be included, I joined their video watching. In this particular instance, they were watching “Ring Ding Dong” (2009) by Korean boyband SHINee. The handsome group members and their catchy songs immediately got me interested in K–pop. I subsequently came across other groups such as BigBang, EXO, 2NE1, Got7, BTS, and Blackpink. K-pop idols exude charisma and confidence on stage, but seeing them on variety shows – where they are funny, clumsy, and playful – is truly fascinating. It is like witnessing two sides of the same person, which makes them even more surprising and endearing. At this point, it was impossible for me not to fall in love.

Uzbekistan is a nation in Central Asia with a population of over 37 million people. In the early 2010s, K-pop struggled to gain popularity there. One rarely came across another K-pop fan in those days, and the idea of seeing idols in real life was unimaginable. Many Uzbeks found K-pop unappealing. Uzbekistan is 94 percent Muslim, and K-pop culture clashed with the more conservative Uzbek culture. I remember being criticized for listening to Korean artists because they contradicted community social norms. For example, masculinity in Uzbek culture differs from K-pop. At least back then, male K-pop stars were more feminine with slim figures and youthful looks, while in Uzbekistan, men are expected to adhere to more traditional ideas of masculinity and maturity. Probably, negative criticism made the youth turn to K-pop as a way of expressing one’s individuality and of rebelling against traditional expectations.

This article narrates how fans experience K-pop in a country usually excluded from the agendas and concert tours of K-pop artists.

Fig. 2: Ailee wearing Uzbek headwear at 2022 Mokkoji Korea in Uzbekistan. (Photo courtesy of the author, 2022)

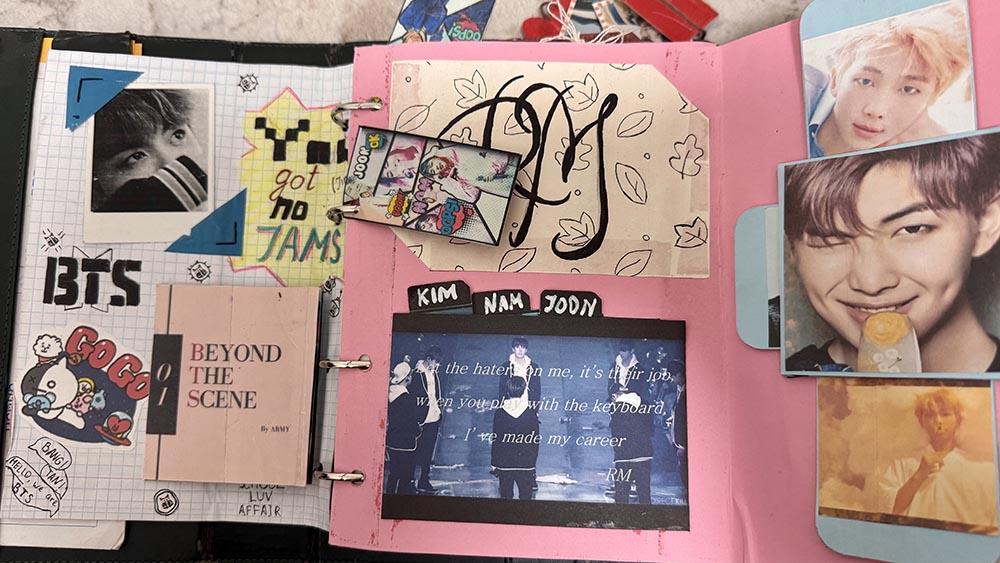

K-pop trends first reached Uzbekistan through Tashkent, the country’s capital city and the most populous city in Central Asia. Yet, even there I struggled to access K-pop merchandise. So whenever I saw any product related to Korean boy bands, I would immediately buy it. It must have been more challenging for fans in other regions of Uzbekistan. Because such products were rarely in stock, I used to make my own K-pop merchandise like notebooks, stickers, or posters. I even made a BTS–themed scrapbook [Fig. 2].

However, in the next couple of years, K-pop started to gain a following among mostly Uzbek girls. There were more online or physical shops that sold Hallyu (“Korean Wave”) products, and there were also more K-pop events. Since 2018, I have been going to the annual K-pop World Festival [Fig. 1], a competition where Hallyu fans are invited to South Korea after going through preliminary rounds in their home countries by performing K-pop songs.

Fig. 2: Scrapbook made by the author. (Photo courtesy of the author, 2018)

Fan groups organize meetings, parties, and charity events to celebrate their favorite artists’ birthdays. They have a good time singing along to popular songs, doing random dance challenges, and playing games. Moreover, the Palace of Korean Culture and Arts in Uzbekistan annually holds Chuseok (Korean Thanksgiving Day), where visitors can enjoy Korean food, traditional and modern performances, and dance battles. The palace opened in 2019 as a symbol of friendship and respect for ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. The event has many visitors, especially fans of Korean pop culture.

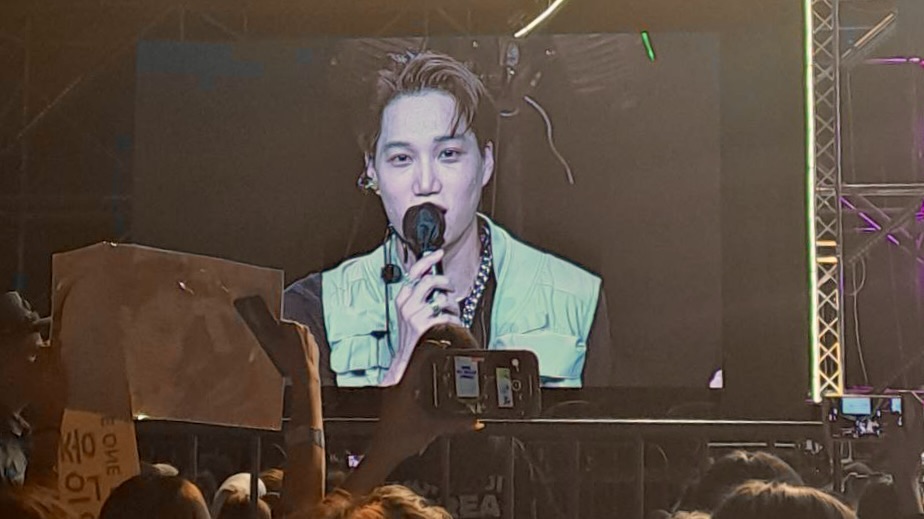

One of the biggest events held in Uzbekistan was the three-day Mokkoji Korea 2022 [Figs. 4-5], a global festival that travels around the world and exhibits Korean lifestyle and culture. The Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of Korea hosts the event, and it is supervised by the Korean Foundation for International Cultural Exchange (KOFICE). Uzbekistan fans could experience a real K–pop concert for the first time with the participation of Kai from EXO, Ailee, and the boyband Fable. Besides the concert, there was a high-five event and an interview with the stars. It received positive reactions as the first project of this kind. The festival provided fans with activities such as K-beauty and cooking classes, wearing a Korean school uniform or Hanbok (traditional Korean clothing), sampling K-snacks, or engaging in traditional games. The event visitors were mostly young females, although there were people of all ages. The unique taste of Korean cuisine, elegant costumes, and well-produced songs made me realize I love Korean culture, and it was not as unreachable as I thought.

Fig. 4: Kai giving an interview at 2022 Mokkoji Korea in Uzbekistan. (Photo courtesy of the author, 2022)

Fig. 5: Ailee performing at 2022 Mokkoji Korea in Uzbekistan. (Photo courtesy of the author, 2022)

Now I am living in Korea as an exchange student, experiencing Korean culture firsthand and living my 20s as I once dreamt. I feel my interest in the Korean Wave had a big influence on my life decisions. For me and many fans, K-pop is more than a pastime: it is an inspiration. Many fans develop new interests or ambitions thanks to their favorite artists. Some get into dancing, singing, or playing an instrument, and many decide to learn Korean. Moreover, idols express their feelings openly about mental health, hardships, and self-love through music, which many Uzbek fans find relatable. Such fans feel comforted knowing they are not the only ones going through hardship and that it is normal to feel different kinds of emotions. They get motivated witnessing their favorite artists’ hard work pay off, and they develop a strong desire to face challenges in pursuit of their ambitions. Many people judge K-pop fans for wasting time and money over childish pursuits, but they fail to realize those ‘crazy’ fans have dreams to achieve something thanks to their passion.

Eshbekova Munisa Jabbor Kizi, born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, is a MA graduate student of Communication at Hallym University (South Korea). She studies media, society, technology, and communication processes. Email: munisa@hallym.ac.kr