A Journey to the West: What Could a Fragment of Porcelain Tell?

China has had a strong presence in the global trade network since the Tang dynasty (618-907). In the early Ming dynasty (1368-1644), more Chinese objects became available to all corners of the world through the maritime network. One of those objects was a typical Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, discovered at Drake’s Bay on the California coast, but surprisingly, this object was later identified as originally made for the Middle East market. Why and how did it diverge from its original destination? What could its unusual “journey to the west” tell? What did California, China, and the Middle East have in common hundreds of years ago?

Origin of the porcelain

The first step to studying this porcelain is to find out the origin of its journey. According to the Hearst Museum archive at the University of California, Berkeley, the porcelain was made in China for markets in the Middle East. Prior to the Ming dynasty, the ruling Yuan court (1271-1368) was the only non-Han dynasty that has ever occupied the entire mainland China in history. Built and separated from the vast Mongolian empire that covered almost all of Asia (including the Middle East), the Yuan dynasty brought many Muslims to China, who were known to the locals as huihui (回回, Muslim). There was even a Chinese slang saying that “Yuan shi hui hui bian tian xia” (元时回回遍天下, “Muslims were all over the world during the Yuan dynasty”). 1 This statement reveled the fact that Muslims, as early as in Yuan dynasty, had already become a vital part of Empire’s population.

When the Ming dynasty overthrew the Yuan, the first emperor of Ming, Emperor Hongwu (洪武), initiated national policies to integrate Muslims with the Chinese. Such policy gave the foundation of the appreciation of Chinese culture within the Muslim community. It eventually influenced Muslims’ lifestyles and attracted them to Chinese porcelains. On the other hand, when Emperor Hongwu founded the new Ming dynasty, many Muslim merchants also left China, as they viewed the political environment as no longer friendly. From the government side, Emperor Hongwu, as the one who had just dethroned a foreign regime to take power back for the Han ethnic majority, wished to re-establish the Chinese dominance. He “discouraged links with the outside world and restricted foreign trade to the level of tribute missions.” 2 That discouragement led to a change in style of Chinese porcelains. The decoration patterns started to emphasize “exactness of execution, symmetry and precise arrangement” instead of the “powerful and vivid” or “strong and impressive” designs that were found on porcelains in Yuan dynasty. However, even with changes in patterns, those artworks were still valued by Muslims. From practices such as interracial marriages, Muslims in China assimilated into the Chinese majority, adopting the latter’s standards of appreciating arts. As Qiu Jun (丘濬), one of the cabinet members in the Ming dynasty, noted, Muslims “after a long time have already forgotten (their differences) and integrated, so they are also hard to be recognized (as Muslims) by their differences (“Jiu zhi gu yi xiang wang xiang hua, er yi bu yi yi bie shi zhi ye” (久之固已相忘相化, 而亦不易以别识之也). 3 While different Chinese people had their own preferences of porcelain styles, Muslims in the Middle East were exposed to fewer types of Chinese porcelains, so they were prone to favor whatever they could have imported from China. Therefore, even with a change in style to be more austere, Chinese porcelains were still valuable in the Middle East market. This consistent love of Chinese porcelains, sometimes regardless of style, explains why the object would be thought as produced for consumption in the markets of the Middle East.

Journey of the porcelain

If this porcelain was originally made for the Middle East, how did it diverge from its journey and land on American soil? The California Historical Society Quarterly reported that the captain of two ships San Pedro and San Agustín, Sebastian Rodríguez Cermeño, carried this porcelain on his itinerary from the Philippines to California. In 1590, the new viceroy of New Spain, Luis de Velasco, was trying to accelerate trade between Mexico and the Philippines, and one of the major difficulties was the lack of a port between trade routes for merchant ships to rest and reload. However, when he was finally granted permission to undertake a port-seeking mission, “he found that there was difficulty in getting funds for the exploration.” 4 Velasco later found Cermeño, who was willing to take the job. After some negotiations between the two of them and the King of Spain, in January 1594, Velasco ordered Cermeño to carry out the mission. In exchange, Cermeño was allowed to generate revenue by selling off merchandise at any new ports he may find. Because this cruise was not a routine practice, Cermeño grabbed all kinds of cargo that he could bring to the potential port for trade, as he did not know whom he would encounter and what goods they would want. Therefore, the porcelain originally made for the Middle East was brought on board and went all the way to America.

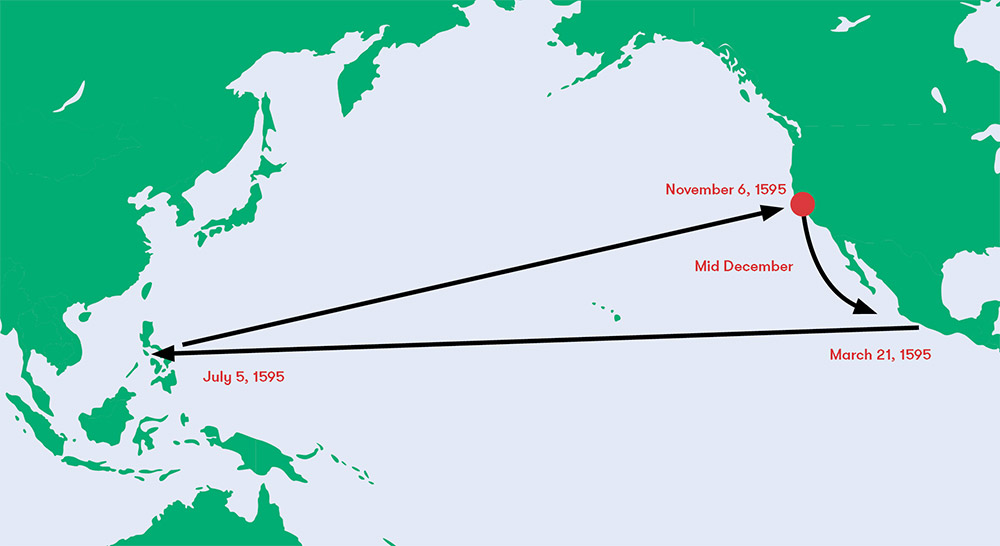

Cermeño spent four months at sea – from July to November in 1594 – traveling from the Philippines to a spot on the coast of California: Drake’s Bay. Upon arrival, Cermeño and his men spent a month on land while encountering some local Indians. In the declaration Cermeño made to claim the newly-found land for Spain, he described that “they [Indians] were all very peaceable and their arms were in their houses, it not being known up to that time that they had any.” 5 The natives also gave their visitors small seeds as food, but these peaceful encounters did not bring the Spanish any luck, as in late November the ship was destroyed by a strong gale. It was assumed that the goods and cargos Cermeño brought with him to trade were lost with the ship, including the porcelain. The rest of the crew struggled to find food and, on December 8, they left Drake’s Bay on a small Philippine ship called Viroco, bound for Mexico for seven weeks [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1: A map of captain Cermeño’s journey. (Figure by the author, 2022).

Though the crew who brought the porcelain to California went home, the object itself did not return and remained there for almost four centuries. In 1970, the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley decided to excavate at Drake’s Bay to find objects that could represent the native culture in the 16th century. At sites called Estero and Cauley, anthropologists found iron spikes and fragments of blue chinaware. Specifically, at some Indian village sites in the Point Reyes Peninsula, archeologists uncovered blue-on-white porcelains fragments. Those porcelain fragments “received a definite identification by Theodore Hobby, assistant curator, Department of Far Eastern Art, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” and they originated from the Ming dynasty in China. 6

At this point a question was raised: as discussed earlier, Ming porcelains were of high value, so how did those fragments remain untouched underground? From what captain Cermeño described, Indians who stayed close to the coast “were looking on with great fright in seeing people they had never seen before” when they met the Spanish crew. 7 Because they were unfamiliar with the outside world, Indians did not hold those porcelains as valuable items: they either “deliberately shattered [the porcelain], possibly to ‘release the spirit’ of the sherds” according to their own culture, or broke them to make “beads, pendants, or scrapers” out of smaller fragments. 8 When those porcelains were broken and deemed not valuable, they “[were] discarded and became scattered in the refuse layers.” 9 Those fragments therefore, lay peacefully for more than 300 years until the discovery by anthropologists of UC Berkeley.

Impact of porcelain

As this porcelain moved between two continents, involving cultures from three geographical regions, it reflected the influence one culture had over the other. In China, as early as the Song dynasty, due to massive demands of porcelains from the Middle East, artisans in the famous porcelain-making town of Jingdezhen (景德镇) started to make their work more to the taste of their customers overseas. They added signature designs like six-pointed stars and Arabian figures to those porcelains intended to be sold to foreigners. Those patterns were not originated from traditional Chinese culture but were common in Jewish or Islamic religions. As to how the Chinese artisans knew how to design patterns with foreign letters, Emperor Hongwu’s friendly policy in dealing with the Muslim minority in China made a major impact. Under Emperor Hongwu, many bilingual Muslims scientists were assigned to the task of translating works that were in Islamic languages to Chinese. This gave an opportunity for Chinese people to understand some of the basics of Islamic languages by directly comparing them to Chinese characters. 10

The direct trade between the Middle East and Chinese merchants also helped artisans in China to perfect their designs of unfamiliar patterns: “the homes of the Quanzhou merchants were famed for their riches, filled with Middle Eastern metalwork that could serve Chinese potters as models, along with carpets and textiles as sources of Islamic design.” 11 As merchants kept bringing works from the Middle East to artisans in Ching-te Chen, Chinese artisans of the latter were able to learn directly from original samples of pottery with foreign patterns. Therefore, with translations of Islamic work and frequent trade with foreign merchants, workers in Ching-te Chen designed many foreign patterns on typical Chinese porcelains, increasing the diversity of not only Chinese artwork, but also of Chinese appreciation of arts. The influence of Islamic designs kept growing in the Ming dynasty, and later under Emperor Xuande (宣德, 1425-1435), the education received by elites eventually incorporated the way Muslims decorated their porcelains as the standard.

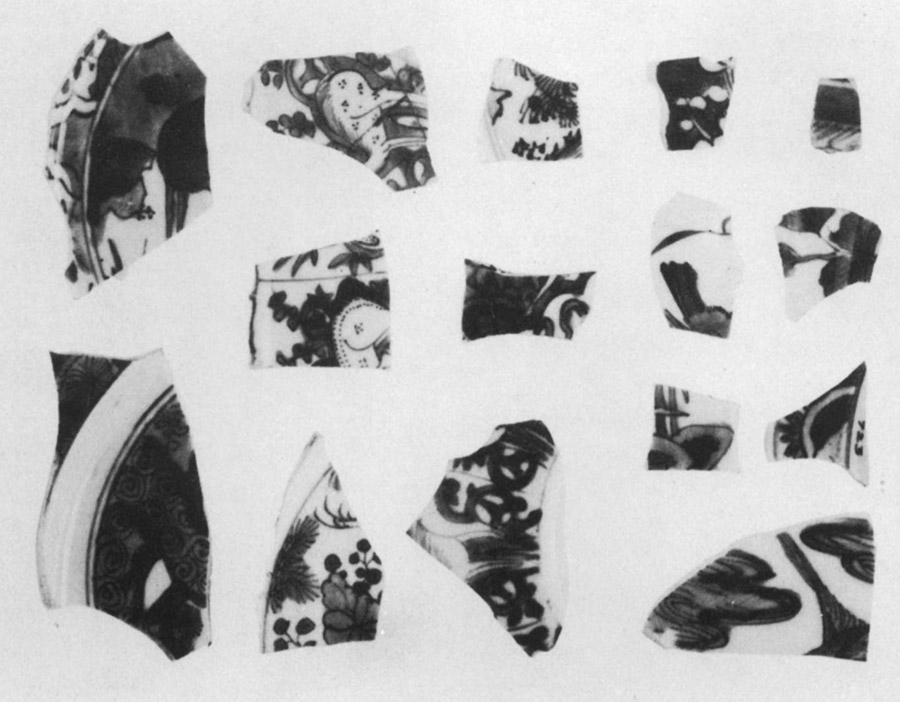

From being integrated into Chinese culture in the Hongwu era to influencing Chinese attitudes to porcelain decorations in Xuande’s time, Muslims became a noticeable force in shaping Chinese culture. In the report of discovery from Heizer about the porcelain fragments brought to Drake’s Bay by captain Cermeño, there was clearly a flowery design with heavy paintings [Fig. 2]. Dated to the 1500s, 100 years after the Xuande period, those fragments are the direct proof of cultural exchange and the adoption of traditional Middle Eastern aesthetics in China.

Fig. 2: Remnants of Chinese porcelains made in the Ming dynasty. (Image courtesy of California Historical Society Quarterly, 1941)

The effect of diversifying porcelain designs by trade was not only on the Chinese side. As Muslims in China helped add foreign patterns to Chinese porcelains, these Chinese products in turn shaped a new appreciation of ceramic art in the Middle East. Amazed by the transparency of Chinese porcelains, artisans in the Middle East were motivated to experiment with new ways to reach the standard of their Chinese fellows. While those experiments in the Middle East mostly failed due to different compositions of clays in the two regions, Islamic artisans successfully took some Chinese styles into their own designs. Before the Ming dynasty, Chinese porcelains were more decorated with asymmetrical patterns, while Middle Eastern arts were more symmetrical. During the process of learning from imported Chinese porcelains, Middle East artisans and patrons adopted freer designs of space, and they welcomed spontaneity and dynamism that were found in the Chinese tradition. Starting by simply copying patterns from Chinese porcelains, Islamic artisans found their way in combining both their own style of strict spacing and the less regulated flow of patterns from Chinese designs. Both patterns initially developed isolated from one another, yet with the development of a massive trading network, both sides took ideas from each other. Before the Ming dynasty, Chinese porcelains were seen as flowing in their designs when Islamic ones were more conservative in spacing. However, when Emperor Hongwu ordered to restrict designs to be simpler, potteries from the Middle East had already incorporated that stylish decoration from imported Chinese work, which later influenced the elite class in China under Emperor Xuande to bring that emphasis on complicated, colorful designs back to Chinese porcelains. Through mutually learning from and influencing the other, Chinese and Islamic artisans had created a new version of porcelain design that combined cultures from two distinct geographical regions.

Beyond connections between China and the Middle East, the link between Spain and China was also crucial in the journey of the porcelain found at Drake’s Bay. Unlike the mutual awareness between Islamic and Ching-te Chen artisans, Chinese workers in the early modern period knew very little about their customers in America. Such unfamiliarity from the Chinese perspective was understandable: the Spanish had little presence in China compared to the massive migration of Muslims during the Yuan dynasty. In order to make a profit from the trade, Chinese artisans needed to prepare a range of their works to make sure at least some of them would be valued by Spanish merchants. This kind of preparation for uncertainty was very similar to captain Cermeño’s approach when he selected the porcelain in Manila for the cruise to America: he did not know his customers either.

To Spanish artisans, on the other hand, Chinese porcelains were familiar. Though they were exposed to Chinese artwork later than the Middle East, Spanish workers were also astonished by Chinese porcelains, which were “inspiring Mexican potters in Puebla to produce their own distinctive blue-and-white earthenwares in order (as an eighteenth-century priest boasted) ‘to emulate and equal the beauty of the wares of China.’” 12 Like Islamic artisans, Spanish and Mexican workers (who fell under colonial rule in the territory known as New Spain at the time) imitated the pattern and style of Chinese porcelains to either add new elements to their own work, or to make similar copies to compete with imported Chinese work in the market. For instance, artisans in the city of Puebla, Mexico kept their ways of making porcelains and other artworks, but also adopted Chinese styles to make products more popular in the local market. Their creation was neither Chinese nor Mexican, but a combination of both to make something original and international. Through the same behavior of learning from Chinese porcelains, Muslims in the Middle East and Spanish in the West also shared a connection of creating arts beyond the culture of a single nation [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3: Example of porcelain made in colonial Mexico. (Art Institute of Chicago, 2022)

In modern times, Chinese porcelains are often valued at an astronomical price when they enter an auction, but behind their price tags is a map of connections between nations’ economies, cultures, and much more. Even some fragments of a seemingly unimportant porcelain discovered at Drake’s Bay reveal a history of massive connections among three distinct locations. This porcelain had no description nor words on it, but it spoke just like one of the four classic books in China, Journey to the West: the journey in the book contained moral values of Chinese society; the journey of the porcelain revealed an adventure of captain Cermeño, and more importantly the influence that China, the Middle East, and Spain had over one another’s culture. From establishing a global trading network, the confluence of their ways of appreciating art was built.

Zixi (Peter) Zhang is a graduate student of Chinese History at Columbia University (United States). His research currently focuses on ways of international engagement between China and its East Asian neighbors in the Ming dynasty. In addition to traditional scholarship, he also uses computer codes to analyze historical documents. Email: zz3004@columbia.edu.