It’s Taking a Whole Village to Raise Children: A Focused Study on the Afghan Refugees in Ulsan, South Korea

In the first five months of 2018, 552 Yemenis, mostly men, claimed asylum on Jeju Island. This was an unforeseen result of a visa-waiver program intended for international tourists who would otherwise have needed visas to enter the Korean mainland. 1 The sudden increased inflow of Yemeni refuges to the island was heavily covered by Korean media outlets, and the so-called “Yemeni refugee issue of 2018” became a wake-up call for Korean society, highlighting the fact that South Korea could receive a large influx of refugees at any time. Four years later, after the fall of Kabul, South Koreans witnessed the influx of another group of refugees into the country, this time from Afghanistan. However, the experiences of these Afghans, as well as the Korean public’s reaction to them, differed greatly from the case of the Yemeni refugees.

On August 26, 2021, 391 Afghans who had worked for years at the Korean embassy in Afghanistan, at Korean hospitals, and at vocational training centers run with Korean support arrived in Korea with their families on a flight chartered by the Korean government “in search of lasting peace.” Upon arrival, they were granted special status by the Korean government as “special people of merit” rather than “refugees.” The news reports and scenes of their evacuation from Afghanistan – which was dubbed “Operation Miracle” – were broadcast in real time by the Korean media, acting as a reminder that South Korea was a responsible member of the international community. In addition, the public discourse on these Afghan “special people of merit” was noticeably different from the perception of refugees that had emerged in the years following the “Yemeni refugee issue of 2018” in that the universal human value of humanitarianism was strongly acknowledged in the case of the Afghan refugees.

Indeed, it can be said that the success and positive perception of “Operation Miracle” was the result of the various resolutions and (sometimes heated) discussions that took place within the religious, academic, media, political, and governmental sectors of Korean society that occurred in the years following the Yemeni refugee issue of 2018. It is of particular interest to note that, rather than being perceived as Muslim refugees, the Afghan refugees were seen as the agents of development and progress following the US invasion of Afghanistan. The term “special people of merit” – as opposed to “refugees” – also played an important role in granting them an identity distinct from the Yemeni refugees.

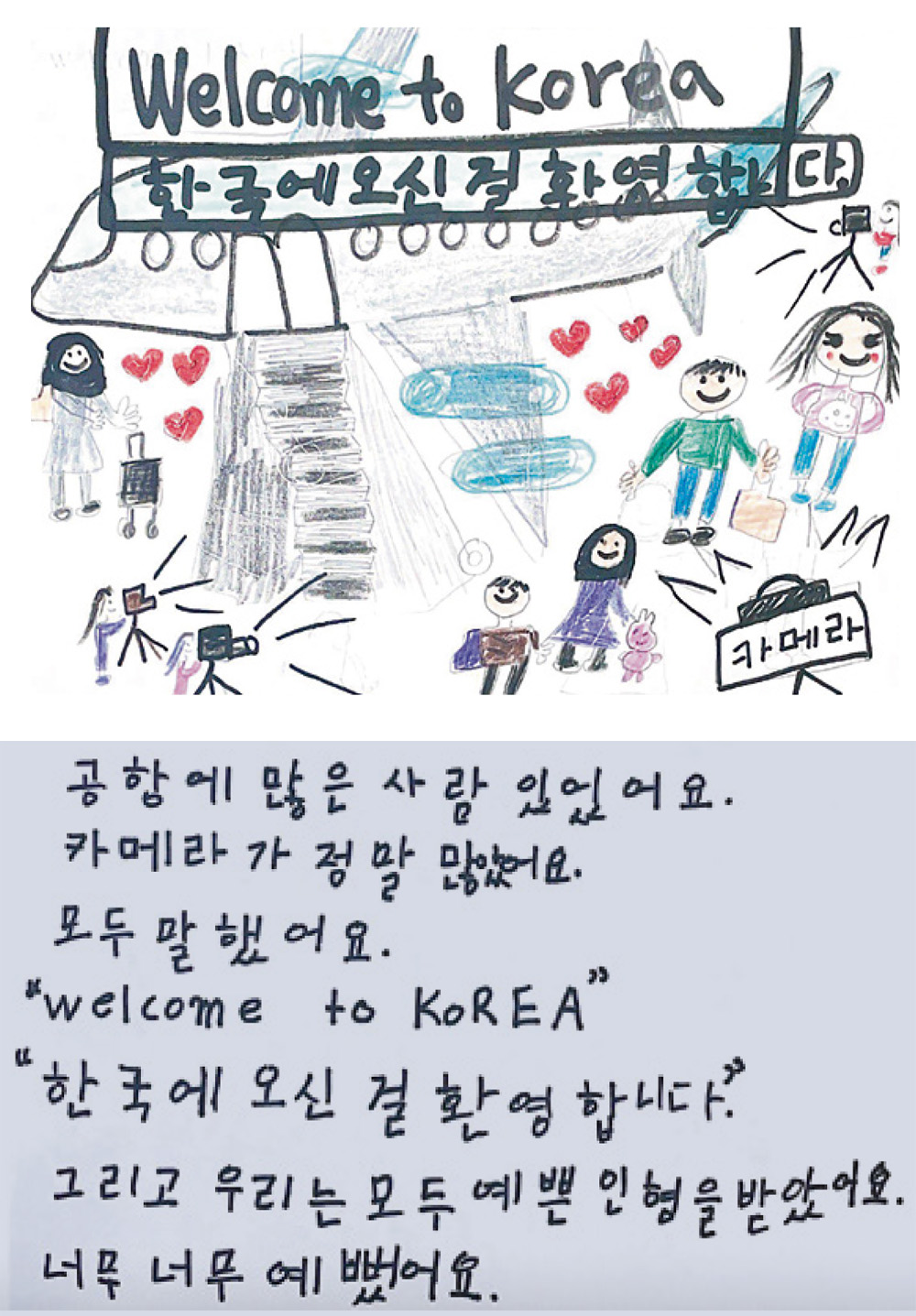

Fig. 1: The largest number of Afghan students were enrolled in Ulsan Seoboo Elementary School. At the end of 2022, Afghan students put together a classroom book called “Shiny Jewelry Box.” This is one of the stories included in this book. The text beneath the picture says “There were a lot of people at the airport. There were so many cameras. They all said “Welcome to Korea.” And we all got pretty dolls. It was so, so pretty.” (Image courtesy of Ulsan Seoboo Elementary School)

Although there were many concerns and controversies during the initial immigration and settlement process of the Afghan refugees, their main settlement area in Ulsan is now transforming into a space of hospitality for Muslim immigrants in Korean society. On February 8, 2022, 157 Afghan refugees, about 40% of the total arrivals, settled in Dong-gu, Ulsan. Twenty-nine heads of households were employed at companies cooperating with Hyundai Heavy Industries, and a total of 85 students were integrated into the public education system in Ulsan: 21 children were assigned to kindergartens, and 64 students were assigned to elementary, middle, and high schools. The Ulsan Office of Education’s multifaceted approach to Afghan students was crucial during this settlement process. A total of five consultations were held before enrollment began, and in the process, the Ulsan Office of Education applied the motto of “education that does not give up on a single child” to persuade local Korean parents who opposed the enrollment of Afghan children.

It has been said that the issue of Muslim refugees in Korea, which arose with the Yemeni refugees, became internalized within Korean society with the case of Afghan refugees. The settlement process of these Afghan refugees is a seminal example demonstrating how Muslim immigrants were able to smoothly settle within Korean society through the multifaceted hospitality and policy support of the Ulsan Metropolitan Office of Education, the city government of Dong-gu District Office, Hyundai Heavy Industries, and the citizens of Ulsan. It is highly possible that this case of ‘hospitality’ towards Muslim immigrants in Ulsan may become a precedent for resolving conflicts in a multi-cultural society, which is a reality South Korea is inevitably headed towards. The diverse subjects and directions of hospitality displayed during the Ulsan settlement process for Afghans will undoubtedly remain a key example in South Korea, and indeed, in Northeast Asia more broadly.

Gi Yeon Koo, HK Research Professor, West Asia Center, Seoul National University Asia Center. Email: kikiki9@snu.ac.kr