Intergenerational Memory and Family Archives

After 1975, South Vietnam lost its legitimate political and archival status in the official historiography both in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) and abroad. This loss gives rise to multiple forms of alternative archiving practices beyond the purview of official archival institutions. These alternative archiving practices are grounded in personal and familial domains where South Vietnamese individuals and families re-narrate and transform histories of the “failed state.” Attention to these practices presents opportunities for conceptual and methodological approaches to studying lived histories of individuals and families that at once entangle with and challenge dominant memory narratives about “failed states.” This article tells a story of my family’s intergenerational archiving practices. Through this story, I grapple with the role of family private documents in preserving and transmitting “lost” histories across generations within and beyond the orbit of official historiography.

It was around 2010, I was too young to comprehend what Grandpa and Mum were doing, nor to realise the significance of this encounter for years to come. I was simply there… to remember. I remember Grandpa and Mum looking worried as their hands hastily yet gently sorted through a spread of papers across the floor of our living room. Those papers were so weathered they all had that sepia colour and those deckled edges. Many of them had been folded in half for so long that the two halves barely hung on to the time-tattered fold lines. Grandpa and Mum handled the papers with such delicacy and care that it made me nervous and surprisingly well-behaved. But those antique-looking papers enchanted me so much that I could not keep my distance from them. Every time my fingers moved in their direction, Mum shooed me away and stretched out her legs between the papers and me. “What is it, Mum?” I asked with frustrating curiosity. Mum did not respond until a while later, “Just some old family paperwork, go play somewhere.” I stayed beside Mum the entire time, sometimes rolling around to Grandpa’s side but never onto the papers. I remember gradually losing interest, feeling sleepy, and dozing off on the floor. Just when my eyes almost shut, I heard Grandpa’s voice, “Found it!” Mum leaned towards Grandpa, inspecting a piece of paper with him, their eyes squinting and moving through the lines of faint writing. They started smiling; the worried looks disappeared. I, too, felt relieved for reasons I could not understand at the time and still cannot now.

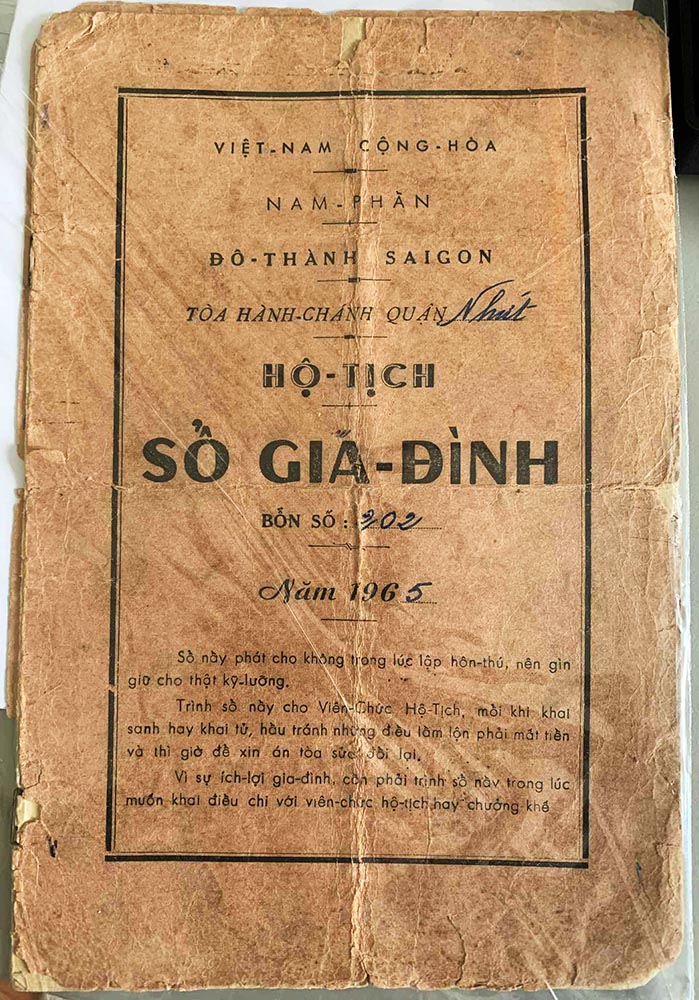

Fig. 1: Household Registration Book administered by the Civil Registration Office of District One, Saigon, 1965. The Book was among the documents that determined my family’s rightful property ownership from before 1975. (Photo by Le Thu, 2025)

It was not until years later that I came to understand what had happened that day. Grandpa and Mum had tried to find family documents from before 1975 for a property dispute they had dealt with at the time. They had been afraid that they could not find the documents needed, as so many of our family’s pre-1975 documents had been irretrievably lost. Family members would frequently recount the dispute in family conversations throughout the years while my younger self would eavesdrop heedfully without understanding much. I gradually came to understand what had happened in the dispute as time went by. Years after the dispute had settled in favour of our family, Grandpa would often say, “See, not all is lost in the War. I’m good at keeping the papers,” with a firm look of pride [Fig. 1]. Then Grandpa and Mum would exchange looks of approval and compliment, but not for too long before Grandpa would shift to an ambivalent, somewhat sorrowful, tone: “Had the South not been lost, we could have just gone to the authority and asked for certified copies of those documents. The new regime keeps nothing of the South.” At those moments, I would get this strange feeling of sorrow and loss for the former southern regime of which I have no direct memory. But before I would wander too far off in my nostalgic imagination of pre-1975 life, family conversations would be filled with stories of the War and South Vietnam – many of the stories would be related to those document papers I grew up seeing. Stories about early 1975 would take me to scenes of chaos and urgency where documents related to the former regime were thrown away, burnt, concealed in locked drawers, taped onto clothes or bodies, counterfeited for various reasons, or handed to the authorities, old and new. At various points in the stories, words from Grandpa and family members would slither away across my ears like swirls of smoke, almost a muffled noise, because all I could see, hear, and feel would be those scenes – all in my imagination. In those fleeting moments of imagination, I belong to a past I have never lived.

The institutionalised erasure of South Vietnam in the SRV and abroad resulted in a specific kind of historical amnesia that does not eliminate memories of the former state, but rather tucks them away in intimate realms such as the home environment, family altars, family documentations, personal feelings, and imaginations. Asian American Studies scholar Quan Tue Tran calls this the “mnemonic splinterings” 1 of South Vietnamese histories. There is a substantial body of works on remembrance in Vietnamese diasporic communities (Yến Lê Espiritu, Long Bui, Linda Ho Peché, Alex Thai-Dinh Vo, and Tuong Vu, to name a few 2 ), which points to the reconstruction of South Vietnamese memories across multiple sites and a wide range of uses and interpretations of the “republican archive.” For example, Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi argues that digital archives mobilize South Vietnamese memories and preserve the cultural identity of the former state outside of SRV censorship and US-led cultural appropriation and misrepresentation of the War and the South Vietnamese army. 3

Indeed, the multiple virtual, informal, and user-run archives across domestic and transnational spaces emerge as counter-hegemonic sites that render present memories made absent by official archives and dominant memory narratives. Cinema and media scholar Lan Duong puts forth the idea of “archives of memory” with respect to the South Vietnamese experience. 4 This concept points to the reconstruction of South Vietnamese memories across multiple sites beyond the remit of the SRV’s erasure and the institutionalised amnesia abroad. Duong highlights the different archives of South Vietnamese memories that denote both the absence and the presence of the former state. That is, on one hand, the SRV’s National Film Institute – as the official state archive – makes absent South Vietnamese memories through omission and appropriation. On the other hand, diasporic films can effectively make present South Vietnamese memories. 5 Similarly, cinema and media scholar Scarlette Nhi Do posits that YouTube functions as a subaltern archive of South Vietnamese memories that preserve the former state’s cinematic materials. 6

Many South Vietnamese alternative archives emerge within non-digital spaces of material family archives. The pluralising forms of digital and non-digital archiving practices highlight the ways in which different archives allow former members of “failed states” to negotiate and reconstruct memory narratives within and beyond intimate scopes of private remembrance. Through archiving practices, South Vietnamese individuals and families navigate their hopes for the continuation of what has been rendered lost in the official historiography by both the SRV and abroad. As lê thị diễm thúy’s The Gangster We Are All Looking For 7 lê thị diễm thúy, The Gangster We Are All Looking For (Picador, 2003) poignantly captures, the afterlife of South Vietnam centres around the idea of mất (“loss”), which shapes a nostalgic hope that the lost state might one day re-emerge in any registers of its afterlife. For generations of my own family, those time-tattered papers are remnants of the former state that re-materialise imaginaries of the “lost” past. They give Grandpa and Mum a sense of hope and belonging to their pre-1975 lives. They also give me a vicarious inheritance of South Vietnamese histories of which I have no direct memory. We sense the fragments and absence of South Vietnamese memories as we touch, see, smell, and feel those tattered papers. Through those papers, we sense the pre-1975 past but cannot touch, see, or smell it. We feel but cannot feel it. But we know it lives on and transforms – at least within ourselves and our archives.

As family generations remember, forget, and pass on intergenerational memories, they preserve but also transform the family archives. Family archivists – family members of different generations – negotiate complex temporalities as part of what literary scholar Hai-Dang Phan calls an intergenerational responsibility to “transmit a linguistic and cultural heritage.” 8 I am now allowed access to those document papers – I have inherited my family archives. I would handle them so scrupulously that stiffening nervousness would shroud the living room until I place the papers back into the drawer intact. Grandpa would always smile at my meticulous care: “That’s right, you kids need to be good with these papers, the last source of family histories, you know.” Then he would recount disconnected episodes from wartime while watching my every move as I put the papers back into the drawer and lock it with the tiny key [Fig. 2]. I would then listen to Grandpa’s stories, with only partial attention because a part of me would daydream about a past I have never lived [Fig. 3].

Fig. 2: Grandpa kept family documents in the altar cabinet before entrusting them to me. Grandpa would carefully squeeze himself in the small space of the cabinet door on the side of the altar as he reached for the documents inside (Photo by Le Thu, 2023).

Fig. 3: Meal offerings to Grandpa on his annual death anniversary in front of the family altar. As I light three incense sticks and whisper my wishes to Grandpa, I wonder if he had kept the documents in the altar cabinet for the protection and blessing of ancestors (Photo by Le Thu, 2023).

Another part of my daydream contemplates the multiple identities I embody when researching with family archives – as a family member, an insider, but also as a researcher, an outsider. As I am writing these words about the role of family archives in preserving and transmitting family histories, I see Grandpa’s smile, pleasant yet nervous. I channel the emotionality of his smile into these lines. I am pleased that Grandpa bequeathed the family archives to me and entrusted them to my research capabilities, which he believed could do some justice to the lost histories of his beloved country, South Vietnam. What justice could I, as a family member and a researcher, do for those time-tattered papers? How could I carry the histories, family heritage, and trust that those papers embody? And with which identities could I carry this baggage? I do not have an answer, and I am nervous. I am nervous that those papers will degenerate into pieces – they will one day. I worry that my understanding of South Vietnamese histories – situated at the intersection of family memories and broader narratives, each entailing distinct political perspectives – would make Grandpa frown because it does not align entirely with the family narratives. I fear that the words I am writing here and elsewhere – nervous and ambiguous – would cast doubt on Grandpa’s trust in me as inheritor of family heritage and South Vietnamese histories. Artist and scholar Grace Pundyk asks, “How could an act of writing serve to responsibly engage with the dead (and largely unknown) when so many gaps exist between the written words I’d inherited?” 9 I am sitting with these time-tattered papers right now, right here, but my attention, partial as it always is, is not in the now nor the here [Fig. 4]. I am nervously reminiscing about Grandpa’s smile, pleasantly daydreaming about the vicarious past, and aimlessly grappling with what to do with remnants of this family history.

Thu Le is a PhD student in Human Geography at the University of Melbourne. Her research examines the cultural-historical geography of memory, emotion, and identity. Her PhD project uses storytelling, sensory-based oral histories, and creative non-fiction to explore how members of the Vietnamese diasporas experience memories of the Indochina Wars. Email: thu.le@student.unimelb.edu.au