‘Hidden-in-plain-sight:’ The presence of social infrastructure in Thingaza Chaung, Mandalay

In March 2021, two months into the most recent and increasingly violent coup d’état, local residents across Myanmar set up small roadside tables with basic foodstuffs under signs marked “po yin hlu, loh yin yu” (“Donate if you have extra, take if you have need”). As COVID-19 spread and the State Administration Council (SAC), the post-coup military government, dismissed public cries for medical assistance and even banned non-SAC distributions of oxygen tanks, residents placed boxes of disposable masks and even oxygen tanks in front of their homes, again with signs that invite passers-by to donate if they have extra and take if they have the need. These locally initiated direct actions are part and parcel of everyday life in Myanmar. They have constituted ayut (places) that cohere into socio-spatial units which could be labelled as neighborhoods.

Rather than the occasional outpouring of mutual aid after natural disasters, Myanmar’s social webs of improvisation serve as the hidden-in-plain-sight social infrastructure 1 that has enabled survival through four coup d’états and six decades of military rule after the country gained its independence from the British in 1948. Under Generals Ne Win (1958-1960 and 1962-1988), Saw Maung (1988-1992), Than Shwe (1992-2011), and now Min Aung Hlaing, the instigator of the 2021 coup, authoritarianism has been the norm. Everyday Myanmar people, like marginalized populations in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and elsewhere, “tend to function as much as possible outside of the boundaries of the state and modern bureaucratic institutions, basing their relationships on reciprocity, trust, and negotiation rather than on the modern notions of individual self-interest, fixed rules and contracts.” 2 These tactical improvisations, however, are not merely “undisciplined” informal practices that dissolve into nothingness once a transaction is complete. As AbduMaliq Simon has argued, when people work with each other across different territories, relations, and spheres of belonging, these “conjunctions become an infrastructure” which is radically open and often invisible but constitutes more than ephemeral intersections because each action “carries traces of past collaboration and an implicit willingness to interact with one another in ways that draw on multiple social positions.” 3

Building Social Infrastructure through Sabbath Day Practices

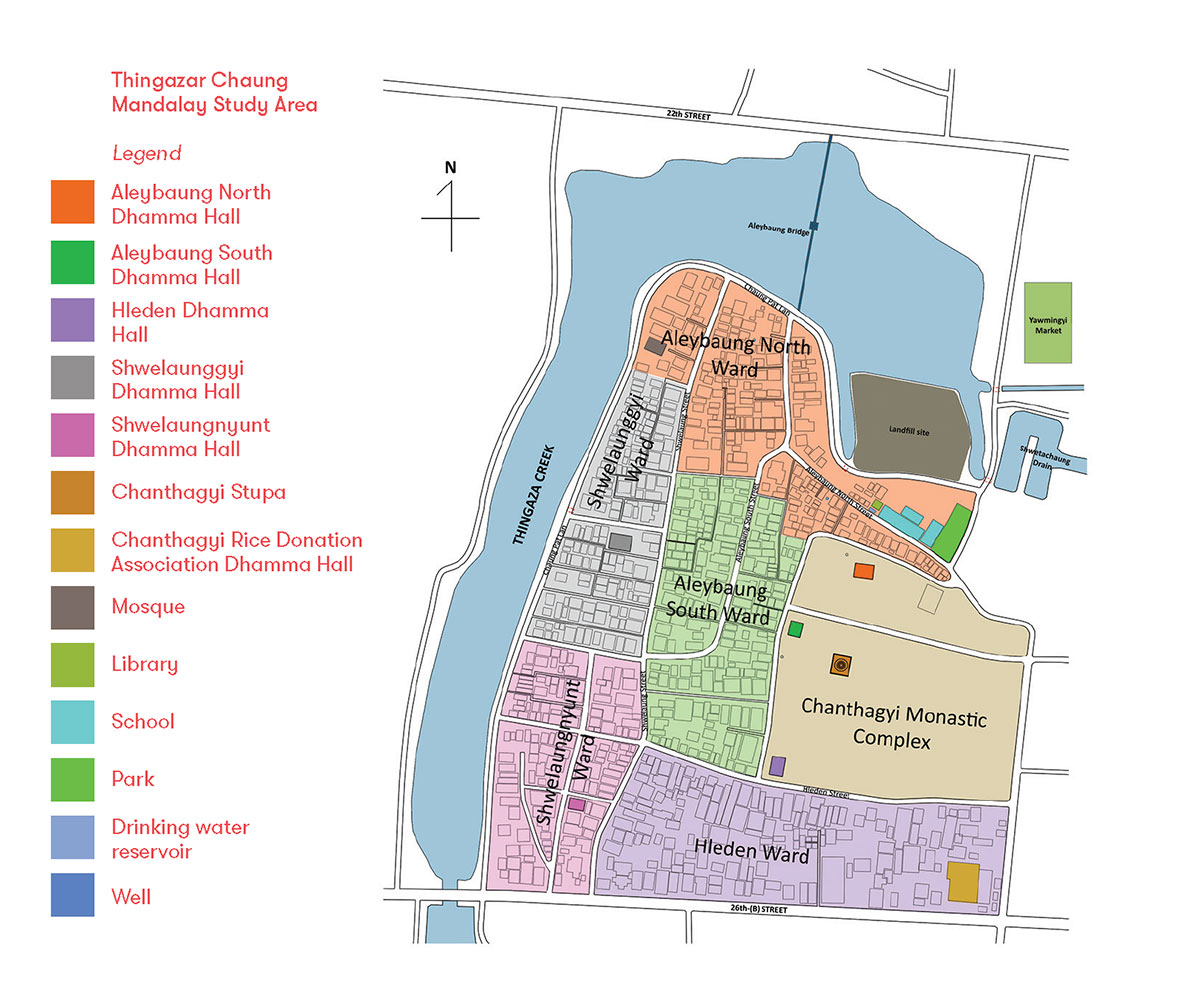

This essay focuses on the collaboration for Upoutnei (Sabbath Days) in Thingaza Chaung, the study area for the SEANNET Mandalay team. 4 It reveals how local residents build and maintain a social infrastructure that is informal but systematic and helps to create place and a sense of belonging.

Every year before Vassa, the annual rainy season retreat observed by Theravadin Buddhist monks, community and religious leaders in Thingaza Chaung hold meetings to discuss how they will host senior monks from the 26 monasteries within the Chanthagyi Kyaung Taik (Chanthagyi Monastic Complex) during the 13 days of Sabbath from Waso to Thadingyut (approximately July to October). 5 The Chanthagyi Monastic Complex grew around the Chanthagyi Stupa, which was built long before the founding of Mandalay in 1857 by King Mindon, the penultimate ruler of the last Burmese dynasty. 6 The residents who live in the six wards that surround the large monastic complex worship at the Chanthagyi Stupa. Like other Burmese Buddhists, they also maintain a symbiotic socio-spiritual relationship with monks, who are seen as “fields of merit.” The laity provide daily alms as well as other necessities for the monks (hpon-gyi, literally “men of great merit”). Through this support, the lay person can accumulate the good merit (hpon-kan) that is required for a better rebirth. In Myanmar culture, the rainy season is seen as a special period for cultivating merit, and the residents of Thingaza Chaung organize special community-based alms giving during these three months.

In the planning meetings, community and religious leaders negotiate the number of senior monks to be invited for each Sabbath Day in each ward. These leaders are not ward level officials but respected members of the community. Once the decision has been made collectively, no ward can alter the number of monks to be invited, and the leader of each ward announces the decision in their respective Dhamma Halls, a community space for religious and social gatherings. In 2018, for example, Aleybaung North Ward was allowed to invite four monks for the first Sabbath and then three monks for the remaining 12 Sabbath Days. Shwelaunggyi and Shwelaungnyunt Wards were each allowed to invite two monks per Sabbath Day. After the number of monks per ward is announced, residents negotiate who will serve as the lead donor for each of the 13 Sabbath Days. They then publicize the list to the entire ward.

The different wards in Thingaza Chaung organize their Sabbath Day donations differently. In Shwelaunggyi Ward, local men start at their Dhamma Hall and march around their area while ringing a gong to collect donations of uncooked rice. This occurs the day before Sabbath in order to donate (hlu) the rice on Sabbath Day. In Aleybaung South, Shwelaungnyunt, and Hledan Wards, volunteers from the Community Men’s Groups walk around to collect cooked dishes in baskets suspended from shoulder poles [Fig. 1]. They use custom-made carriers wherein each donated dish is placed in identical metal bowls that rest neatly in the metal basket.

Fig. 1: Volunteers from Aleybaung South Ward collecting donated dishes with custom-made carrier (Photo by May Thu Naing, 2018).

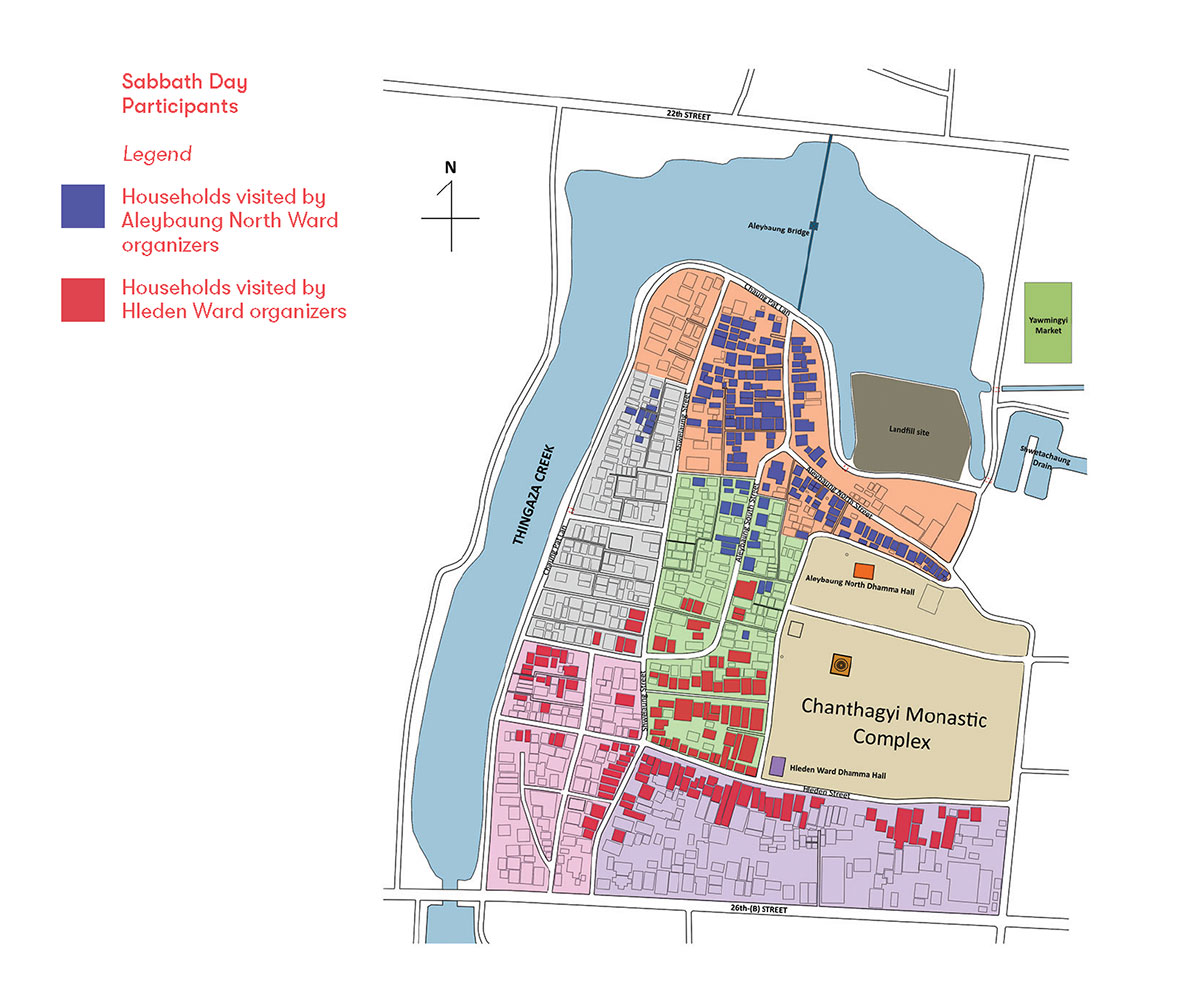

In Aleybaung North Ward, the Community Women’s Group organizes a more festive procession that starts at six o’clock in the morning, which includes not only women but also young men and children. In this ward, the number of dishes is precisely calculated to provide enough food for the number of monks invited and the number of households participating in Sabbath Day. All of the participants carry metal circular platters with small metal bowls to receive the donations of prepared dishes. Once each platter is full, the dishes are delivered to the Dhamma Hall and transferred to larger containers so that the small dishes can be washed and sent back out for more donations. The women, men, and children ring gongs and march through the streets and alleyways in their own ward as well as adjacent wards where the Women’s Group has been invited [Fig. 5]. Former neighbors who moved out of Aleybaung North due to marriage or other reasons welcome the opportunity to support their old neighborhoods and ask to be included in the Sabbath Day donation rounds. In Hledan Ward, the local organizers expanded their area for soliciting donations to include friends living in Aleybaung South because Hledan, as the smallest ward, does not have enough households to generate a sufficient collection of food for the monks.

In all wards, the procession ends at their respective Dhamma Halls. Here, as the dishes arrive throughout the morning, community leaders and volunteers categorize the different dishes according to type and apportion them equally for the invited monks. The senior monks are then served some special dishes such as mohinga (Burmese rice noodle and fish soup) and later escorted back to their monasteries with a large selection of food for other monks in their monasteries. In addition, the lead donor of each Sabbath must prepare food for the volunteers and community members who practice the Eight Precepts for Sabbath. Community members are served after the senior monks have taken their meals. Sometimes, lead donors also offer soap, cold drinks, and snacks to the volunteers and participants. Anyone who passes by and expresses interest in the event is welcomed into the Dhamma Hall to partake in the ceremonies and share the food as well as the gifts of soap and other items. When all of the food has been served, the organizers and volunteers wash all of the dishes and clean the Dhamma Hall. Sabbath Day concludes around 10:30 in the morning.

These annual holy days, which take place for 13 consecutive weeks and are organized by six adjacent wards to honor senior monks from 26 different monasteries, require systematic coordination. Buddhism is a hegemonic force in Myanmar that has both united and divided local, regional, and national populations. At the scale of townships, the administrative level above wards, the desire to appear more devout has led to ward-level competitions expressed through the number of senior monks hosted, the types of dishes served, and the general liveliness of Sabbath Day events. The women in Aleybaung North proudly described how their shwegyisanwinmagin (Burmese semolina cakes) are known as the most delicious in the area and how residents in neighboring wards come over to their Dhamma Hall to “eat for free.” This effort to outperform each other is largely friendly and jocular but requires regular management to keep peace within the township. This is done every year through the pre-Vassa meetings, wherein community and religious leaders can reach a mutually acceptable agreement that is then honored in practice.

This level of accountability is uncommon in Myanmar’s state-society relations. Governance reform between 2011 and 2021 struggled to increase trust in the municipal and national governments. Most people approached laws and policies with scepticism, often only complying with regulations if compelled by force. In contrast, the rules established through the pre-Vassa annual meetings are respected throughout Thingaza Chaung and foster a lively order during the 13 weeks of the rainy season. This social order is also notable because it both maps onto and transgresses administrative ward boundaries. As described above, the women in Aleybaung North take their procession into adjacent wards: Shwelaunggyi and Aleybaung South. Meanwhile, the organizers in Hledan collect donations from Aleybaung South and Shwelaungnyunt Wards. Some of this transgression is unsurprising, as neighbors who face each other along a single street often associate with each other even if their homes fall in separate administrative zones. The red houses along Shwelaung Street belong to two different wards but work together for collecting special dishes for the monks.

Fig. 2: Ward boundaries as described by local residents. Current maps at the municipal level do not match maps at ward levels (Map created by May Thu Naing and Kathy Khine).

Fig. 3: Houses visited during Sabbath Day Alms Procession (Map created by May Thu Naing and Kathy Khine).

Other lapses, however, reveal relationships that would be subtle – if not hidden – without ethnographic attention to fleeting practices such as Sabbath Day processions. The women of Aleybaung North visited all of the houses in purple even though some of these families technically belong to the Shwelaunggyi and Aleybaung South Wards and should be more loyal to their own Dhamma Halls. This collaboration across ward and Dhamma Hall boundaries is significant because religious practice is a central determinant of social belonging in Myanmar, subject to both praise and censure. As giving food to senior monks is held in the highest esteem, the purple households in Shwelaunggyi Ward likely enjoy communal recognition for their good deeds and would suffer no negative consequences if they donated twice, to the collection efforts of both Shwelaunggyi and Aleybaung North Wards. 7 Adherence to traditional Buddhist social norms is still very strong in contemporary Myanmar. These boundary-crossing networks show how people-to-people relationships can transcend more constrained administrative definitions of belonging and encourage accountability through collaboration.

Streets and Dhamma Halls as Social Infrastructure

The 13 Sabbath Days of Vassa are not celebrated in every ward or township in Myanmar. In Yangon, the country’s largest city, none of the SEANNET researchers have seen donation processions during the rainy season but we have seen similar collaborative efforts for other holidays. In all cities, neighbors come together to celebrate Kahtein, the festival at the end of Vassa when the laity donate the Eight Requisites to Buddhist monks, and Thadingyut, the festival when residents line their streets with colorful lights and candles to welcome the Buddha and his disciples. For these and other Buddhist holidays, self-organized street and ward committees plan for the celebrations by setting up temporary pavilions on their streets [Fig. 4]. They solicit donations by broadcasting Buddhist chants and shaking aluminium donation bowls that clang with the sound of coins. They also invite venerable monks to give Dhamma talks and hand out mohinga and other free food to residents in the neighborhood and anyone who happens to walk by. These activities transform the street into a shared living room of sorts, where neighbors sit and chat in the pavilions, where volunteers cook and distribute the mohinga, and where children run around enjoying the festivities.

Fig. 4: Temporary pavilion set up for Kahtein (Photo by author, 2008).

Similarly, residents who live near Dhamma Halls use these spaces to celebrate different holidays and hold community events. As the halls are generally small, activities spill out onto the street, once again creating an open, shared space where local residents and visitors are welcome. As permanent structures, however, Dhamma Halls are generally more regulated, and non-Burmese Buddhist populations such as long-resident Muslims have felt excluded. 8 Nonetheless, these temporary but periodic celebrations that reconfigure the streetscape create and maintain a social and spatial infrastructure. They encourage neighbors to negotiate the various requirements and inconveniences of hosting the event, such as blocked streets, the noise of pre-recorded chants broadcasting from early morning until late at night, the social expectation to volunteer to cook or clean up, and sharing in the cost of hosting the event overall. Through these periodic negotiations in specific locations, the neighbors generate a place, a sense of neighborhood that coheres but remains open to renegotiation. Their collaboration for one festival sows a seed of willingness for future cooperation, weaving together a relational infrastructure predicated on people and place.

This “people as infrastructure” is not free from coercion or abuse. In the context of Myanmar, six decades of authoritarian rule has left its residents with few choices but to fend for themselves, whether that means collecting special meals for monks or ensuring neighbors have enough to eat under a coup-induced state of emergency. The above analysis is not a naive celebration of local initiative as resilience nor a dismissal of state failures. Rather, it seeks to highlight the systematic quality of collaboration that not only produces successful Sabbath Day celebrations but maintains community relationships from year to year. This systematic, locally organized, and long-term collaboration could be conceived of as a basis for a mutually negotiated form of local governance, one that might engender a participatory democracy which has eluded Myanmar despite the promotion of free and fair elections.

Jayde Lin Roberts (International Principal Investigator, SEANNET Mandalay team), UNSW Sydney, Australia, j.roberts@unsw.edu.au