Hanguk or Joseon? Republic of Korea, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and the Complex Nature of Reference to ‘Korea’

Escapees from North Korea face numerous challenges upon arriving in South Korea, with cultural and language barriers being one of the most significant. As of 2023, approximately 34,000 North Korean defectors reside in South Korea, 1 contributing to the complex social fabric of the nation. The 2024 appointment of Thae Yong-ho, 2 a former senior North Korean diplomat, to a vice-ministerial position in the South Korean government, symbolises the growing political and social integration of defectors. However, despite such seemingly positive advancements, the societal stigmas faced by North Korean defectors remain significant.

Although the Korean language contains examples of ethnocentric nation-building 3 and unification in the form of terms such as Ournation (urinara) and Ourlanguage (urimal), it is arguable as to whether these envelop the whole of the Korean diaspora or, indeed, in a more tribalistic sense, simply those born and raised in South Korea. The discrepancy may be seen in the rhetoric of the South Korean public, with expressions such as ‘North Korean vocabulary lookup in Ourlanguage’ visible in the titles of certain publications. 4 Such usage may be seen as rather ironic (and arguably reflective of actual, contemporary South Korean identity as opposed to that prescribed by institutions such as the National Institute of the Korean Language), as the official definition of Ourlanguage (urimal) is ‘the language of the people of Ournation (urinara)’. 5

In this essay, I focus on the ideological discrepancies in the naming of ‘Korea’ and everything that is ‘Korean’ – something that is often overlooked in English translations of both South and North Korean written matter. Although the arguably ‘subtle’ differences in the naming of a country (i.e., the equivalent of ‘North’ and ‘South’ Korea in many Indo-European languages) may seem trivial for audiences from some linguistic backgrounds where the difference is not as linguistically marked as in languages with Sinoxenic (Chinese character) vocabulary, inadvertent misuse and misnomer may have repercussions for both source (victim) and target (perpetrator) culture individuals.

‘Han’ and ‘Joseon’: Two Koreas

Although the Korean language is fundamentally the same in both North and South Korea, it has diverged significantly due to the 70-year separation and differing sociopolitical conditions. 6 Korean in South Korea has been heavily influenced by foreign languages, especially English, due to globalisation, while North Korea has taken a purist approach with some Soviet Russian influence.

Korea was unified under the Joseon Dynasty for over 500 years until the Korean Empire was established in 1897. Following Japanese colonisation (1910–1945), the Korean Peninsula was divided after World War II, with the Soviet-backed North becoming the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the US-supported South forming the Republic of Korea (ROK). The division also created differences in how each side refers to ‘Korea’. North Korea uses ‘Joseon’ (from the Joseon Dynasty), while South Korea uses ‘Daehan’ (from the imperial period). This distinction is not mirrored in English, where both are often referred to as ‘Korea’.

In everyday language, North Koreans refer to their country as ‘Joseon’ and South Koreans as ‘Hanguk’, extending the terms to other national symbols such as the Korean alphabet, which is called ‘Hangeul’ in the South and ‘Joseon-geul’ in the North. The Korean Peninsula is similarly referred to as ‘Han bando’ (bando meaning peninsula) in the South and ‘Joseon bando’ in the North. These distinctions indicate political or ideological alignment, especially when terms like ‘Joseon Peninsula’ are used in the South or ‘Hangeul’ in the North, raising eyebrows due to their symbolic significance. In languages other than Korean, the situation is even more complicated. For example, in Japanese, South Korea is called ‘Kankoku’ (Hanguk) while North Korea is ‘Kita Chōsen’ (Buk Joseon, ‘Kita’ the Japanese kun-yomi reading for ‘North’), therefore somewhat reflecting the use in the respective countries.

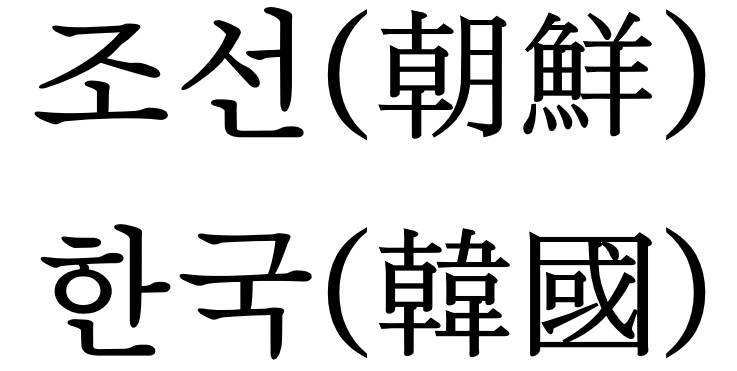

Fig. 2: Visualisation of the difference in the general words for 'Korea' as normally used in North (Joseon) and South Korea (Hanguk) and, in brackets, the relevant Chinese characters. Source: Adam Zulawnik.

In North Korea, using ‘Han’ for Korea has been illegal and highly policed. For instance, during a visit by South Korean President Kim Dae-jung in 2000, North Korean media reported he arrived on ‘H Air’ instead of ‘Daehan Hang’gong’ (Korean Air). More recently North Korean officials have referred to South Korea as ‘Daehan Minguk’ (the official term used in South Korea), to reflect a view of the South as a separate nation and enemy. 7

In South Korea, there are no bans on the usage of ‘Joseon’ (in fact, one of South Korea’s major newspapers, the Chosun Daily, is literally the Joseon Daily). Nevertheless, there is some stigma in relation to the term Joseon being used in reference to the Korean people, as it is associated with North Korea and the Japanese colonial period and sometimes used as a racial slur in Japan towards South Koreans. 8 According to some historical sources, patrons of the American-backed interim government in the South held a vote in 1948 to decide on the naming of the new government, 9 with 17 votes going towards Republic of Korea (Daehan), seven towards Republic of Koryo (Koryo originating from the ancient Koryo Kingdom), and two towards the Republic of Joseon (the same term for Korea now used in the North).

Koryo is used sporadically in both the North and South as well as in reference to the Korean diaspora in Central Asia (known as ‘Koryo saram’). The term ‘Koryo’ also made a brief comeback in 1980, 10 when Kim Il-Sung, the founding leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, proposed a ‘Democratic Confederal Republic of Koryo’. Historical sources note that proponents of Daehan (the term used now in the South) – such as politician and Korean independence activist Jo So-ang – argued that the Japanese colonisers tried to eradicate the term in favour of ‘Joseon’, which is “symbolic of sadaeju’ui”, 11 a largely pejorative term often used in reference to historical Korean reliance on China (within a Sinocentristic world order), particularly during the Joseon Dynasty. 12

It is, therefore, the combination of such narratives and historical flows (including naming decisions made by a select few on both sides) that have resulted in a relatively complex socio-political situation, often overlooked by languages outside of Asia. And yet, the name that we go by, or choose as self-reference, have been a hot issue historically, including in the Anglophone world. 13

The heightened sensitivity of South and North Koreans to misnomer may be seen as linked to the very plurality of ‘Korea’ in the Korean language, and ideologies imparted through decades of education. This can sometimes lead to misunderstandings and a lack of objectivity, such as when interacting with states such as Japan, China, and Vietnam, who choose a more diplomatic approach to nomenclature. Regardless, considering the importance of naming in ascertaining collective identity and positionality, all nations should have the right to be referred to using their own naming convention of choice (within contextual reason).

Adam Zulawnik is Lecturer in Korean Studies at the Asia Institute, The University of Melbourne. Email: adam.zulawnik@unimelb.edu.au

This article is a shortened version of an article originally published by Melbourne Asia Review, Asia Institute, University of Melbourne.