The Golden Voice: Graphic Novels and the Khmer Republic

Until 1975, the music and film industry in Cambodia was flourishing. Yet, to date, not much scholarly study has been done on cultural life in the Khmer Republic. 1 It is music, perhaps, which evokes the memories of that period most strongly. The haunting voices of the dead have survived to this day through records carefully kept, recovered, and remastered, or through lesser-quality versions shared on YouTube and Spotify.

Gregory Cahill’s and Kat Baumann’s graphic novel The Golden Voice – about famous female singer Ros Serey Sothea – was published in both English (2023) and Khmer (2022). 2 It is the result of many years of work. 3 Director and screenwriter Gregory Cahill’s fascination with Cambodia’s music from the 1960s and early 1970s began in 2005 with the soundtrack of Matt Dillon’s movie City of Ghosts (2002), the first big foreign feature film to be shot in Cambodia. Yet, as Cahill recalls his first encounter with this music, he remembers another story. In the summer of 1984 or 1985 – he was very young then – his parents hosted a big party in their backyard, with over 100 people in attendance. Most of the children did not speak English. It was only later that Cahill understood that it had been a welcome party for Cambodian refugees recently arrived to Massachusetts from refugee camps in Thailand.

In 2006, when Cahill was a young graduate from film school, he decided to make a movie about Ros, and his father put him in touch with some of the former refugees. They gave Cahill further contacts of friends and relatives in Long Beach. Many came from Battambang, Ros’s home city. The enthusiastic reception of his short film The Golden Voice at the Cambodian Students Society (Long Beach) convinced him to develop the project into a full-length feature movie. In 2007, he made his first trip to Cambodia for research. His guide and mentor there was musician and human rights activist Arn Chorn Pond, a good friend of Ros Serey Sothea’s sister Ros Saboeun. Through them, Cahill met other primary sources, mostly musicians and actors. He thinks they also managed to find the village where Ros died in Kompong Speu province. There, they met an older woman, who said she had lived in the village during the Khmer Rouge period. They did a bit of digging, and she clearly knew things she could not have known otherwise, such as the names of Ros’s brothers and sisters.

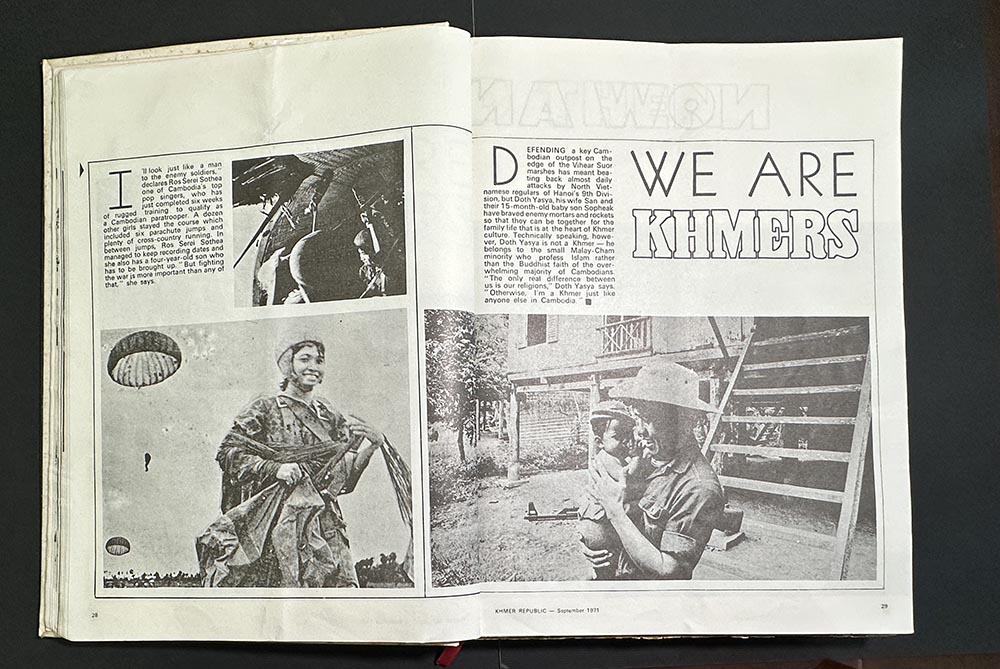

The project went into development with different companies. Cahill had in mind an epic period picture, but it was too expensive. After ten years, he decided to turn the project into a graphic novel and adapted the script to a storyboard. He hired artist and comic illustrator Kat Baumann in 2019. 4 To help her recreate Ros’s environment, Cahill provided Baumann with a massive photographic archive, including family pictures as well as more general images of architecture, clothes, hairstyles, cars, and military equipment [Fig. 1]. As Baumann got further into the process, she also did additional online research for specific visuals, for instance the plants native to the different regions in Cambodia. 5 There were then only two silent films with Ros in existence. The first was a clip of her as a paratrooper interviewed by a French magazine [Fig. 2], and the second showed her in army uniform with another female singer at Wat Phnom for a concert celebrating the Republic’s second anniversary in October 1972. Cahill shared the second clip on social media, and within ten minutes, a Cambodian friend commented that the woman next to Ros was his aunt, still living in Long Beach. Seng Botum was an actress in the 1970s, and she was also best friends with Ros. Seng had many stories to tell, and some made their way into The Golden Voice. When interviewing witnesses, Cahill had to rely on memories from 60 years ago. There were contradictions. His policy in general was to stick with the Ros family’s version. The end of the graphic novel lists the differences between real and fictionalized events.

Fig. 2: Ros Serey Sothea completing her training as a paratrooper, monthly illustrated magazine Khmer Republic, vol. 1, no. 1, September 1971 (photographer unknown).

Cahill was keen to have the music in sync with the graphic novel. In collaboration with the Cambodia Vintage Music Archive (CVMA), 6 he introduced a QR Code that made it possible for readers to stream a soundtrack of 47 songs he had curated (Ros had recorded some 500 songs in her career). Socheata Huot from Avatar Publishing expressed her interest in a Khmer translation of The Golden Voice. The launch of the Khmer version was organized at Bophana Center in Phnom Penh, with hundreds of people cramming to in the gallery (November 2022). In 2023, Les Humanoïdes Associés (Humanoids) acquired the worldwide rights for publication. The launch party in the United States took place in Long Beach. Members from Dengue Fever – the Cambodian-American band that had been instrumental in reviving Cambodia’s psychedelic rock from the 1970s – and CVMA played and DJ-ed. The story of The Golden Voice is far from over yet. In March 2024, the Cambodian theater company Khmer Art Action announced that it would turn the graphic novel into a musical, which is currently under development.

Many artists died during the Khmer Rouge regime. Many works disappeared. There have been initiatives to find and preserve these materials and bring this cultural legacy to the public. The Golden Voice is one of them, and the ways it has been received by the public show the importance of collecting, researching, and sharing these works and life stories in Cambodia and the diaspora.

Stéphanie Benzaquen-Gautier is a visual historian, currently a Research Fellow at IIAS. Her work explores violence, archives, memory, and activism in Cambodia. Email: sd.benzaquengautier@gmail.com