On Digital Engagement, Sameness, and Our Ability to Discern

For researchers and students, digital engagement continues everyday, during and off work. A text-prompt A.I. artwork of a swamp of presentness is filled with digital sameness [Fig. 1]. My apprehension emerges from this techno-sensorially enhanced presentness affecting our ability to discern. Everything is equivalent in this mediation, a throwback to the time digital technologies were held by default a democratic tool. Today, as billions record their thoughts in public, the echo chamber of social media is an imperfect mirror to reality, its biases now making the swamp of presentness more difficult to disengage.

Reflecting upon the moment needs knowledge of background, structure and the dynamic between them. It is difficult, more risky when surrounded by the provocations of presentness. In the teaching-learning world of the humanities, a route is sometimes made by holding dear the comfort zone and associated risk averse imaginations. Subverted by the consumerism of objects, trends, and ideas, it becomes near impossible to imagine an autonomous professional, leave alone be one. Between discipline and subject, specialisation and area, it can feel almost dangerous to break the mould. Exercising self-control, also known as self-censorship, becomes a laudable public act.

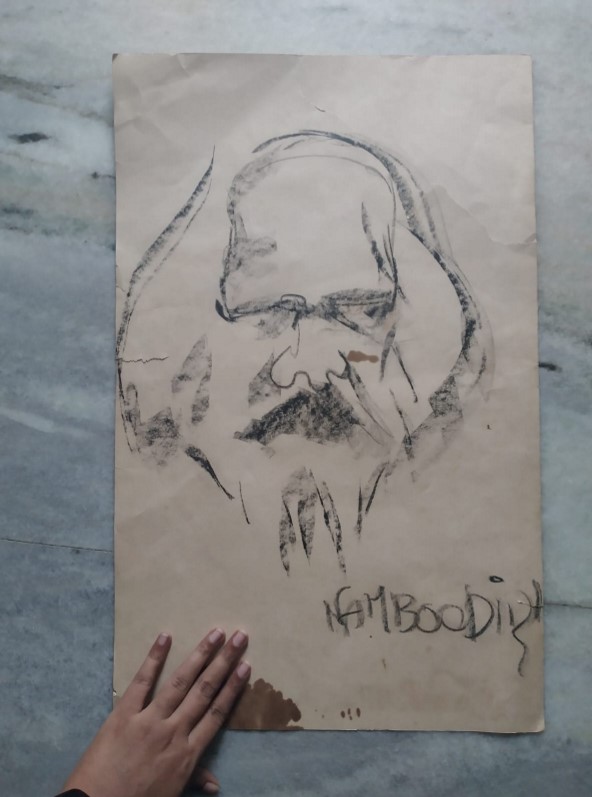

Fig. 2: Image posted to the social media of the author’s colleague, holding a sketch of her grandfather, “Artist Namboodiri,” by G. Aravindan.

On the other hand, there are those who are struck with ennui, an overwhelming need to escape the presentness. A couple of hours ago, I saw on the social media of a 30 year old colleague, a post on the passing away of 97 year old ‘Artist Namboodiri,’ legendary painter from Kerala. It is a sketch by him of G Aravindan, iconoclast filmmaker, who had died even before my colleague was born. It is a family treasure, taken out to be shared, this time on social media. Her hand holds the crumpled paper down, as she takes the picture, a silent acknowledgement of listening to those who have trudged through the swamp before [Fig. 2].

I am glad that some are looking back from the present and making their own connections to the past. It’s a long way home, but it is the only way.

Surajit Sarkar, Ambedkar University Delhi, India