Culinary "Dakwah": Hui and Chinese Muslim Restaurants in Malaysia

In 2015, I dropped by “China Muslim Authentic Heritage Pulled Noodle Restaurant,” a Hui restaurant in Bangi, a Muslim-majority suburb near Kuala Lumpur. While watching the live demonstration of Hui making noodles, I talked to Said Pan, the restaurant manager. His brother Hassan Pan, originally from Lanzhou in Gansu, came to Malaysia to open his first restaurant in 2013. His business has increased since then, as his restaurants have been very popular among middle-class Malay Muslims. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, it had more than 30 branches across cities in Malaysia.

Bangi, a middle-class Muslim neighbourhood, has many Chinese halal restaurants; some are run by Hui migrants, such as Xin Jiang Restaurant, Salam Noodle, and Hot Meal Bar. Others are run by local Chinese converts, such as Mohammad Chan Restaurant and Haslinda Sim Restaurant. All these restaurants claim they serve halal and authentic Chinese Muslim food. Some of the restaurant owners also see food as a medium of dakwah (Islamic preaching), a trend which I understand as culinary dakwah. But what is ‘authentic’ Chinese Muslim food? Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as Chinese Muslim cuisine, as regions, not religious affiliations, primarily define Chinese foods. Hence, Chinese Muslim food means halalized Chinese food of any type. Halal – literally meaning “permissible” – might entail different meanings for different people, but put simply in the context of Chinese halal food, it refers to Chinese food without using pork, lard, or any other non-halal ingredients. Many Chinese foods in Malaysia have their origins in Southeastern China (especially Cantonese and Fujian traditions), with many local inventions. However, new Chinese migrants, including the Huis, brought new additions over the last decade. Hui restaurants offer a mixture of Northwestern Chinese and Xinjiang dishes, yet repackaged as “authentic Muslim cuisine from China.” Their signature dish is Lanzhou pulled noodle (lamien), best known as “mee tarik,” a new term that Hui migrants have brought into Malay vocabulary.

Fig. 2: Localized fusion lamien dishes - golden curry lamien and fried lamien (Photo by the author, 2019)

It is essential to clarify the different meanings between Chinese Muslims and Hui Muslims in this essay. I use Hui mainly to refer to Chinese-speaking Muslims from China, while Chinese Muslims refers to Chinese Malaysians who have converted to Islam. Today, most Chinese Muslims in Malaysia are the third or fourth generation of non-Muslim Han Chinese migrants from the southeastern regions of China; many of them are converts. Meanwhile, many contemporary Hui migrants in both countries come from the northwestern part of China, especially the Gansu Province. As in Mandarin Chinese, many overseas Hui prefer to identify themselves as zhongguomusilin (中国穆斯林Chinese-national Muslims), while local Chinese Muslims call themselves huarenmusilin (华人穆斯林ethnically Chinese Muslims). In English, though, the common use of “Chinese Muslims” might cause some confusion, as some Hui restaurants also label themselves “Chinese Muslim” (in English) but refer to the zhongguomusilin restaurant. Despite cultural and religious affinities, as well as their close relations, there are certain significant differences between Hui migrants and local converts that make Hui and Chinese Muslims two different yet closely related groups. Such differences are reflected by their dialects, food, cultural celebrations, religious upbringings, citizenships, and so on. For example, most Hui Muslims do not celebrate Chinese New Year, yet such celebrations play an important role in identity formation when it comes to Chinese Muslims in Malaysia.

Eating places in Malaysia and elsewhere have drawn scholarly attention, as they provide tangible and lively examples of various social issues, including middle-class consumption, ethnic interaction, and religious practices. The halalization of local Chinese food, the cuisine brought by Hui migrants – and the adjustments made to accomodate local taste and Islamic requirements –define what constitutes “Chinese halal food” in Malaysia. The quest for ‘multicultural’ and halal consumption among urban middle-class Muslims has contributed to the recent growth Hui and Chinese Muslim restaurants in Malaysia. Such restaurants are sites of identity manifestation, culinary dakwah, halal consumption, and ethnic interactions in Malaysia.

Sites of identity manifestation

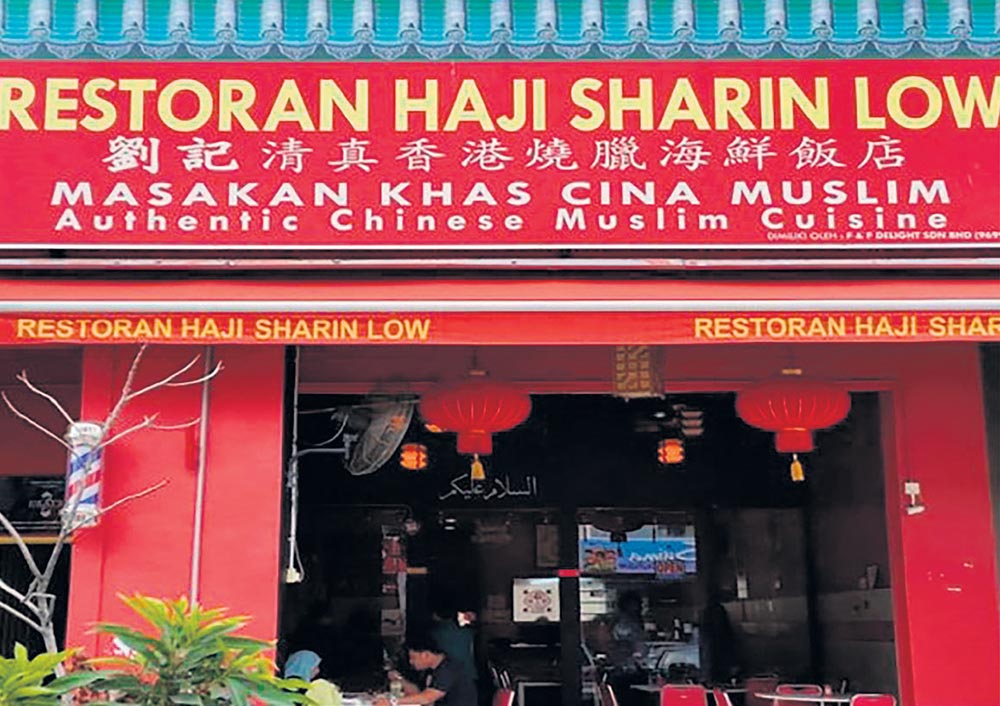

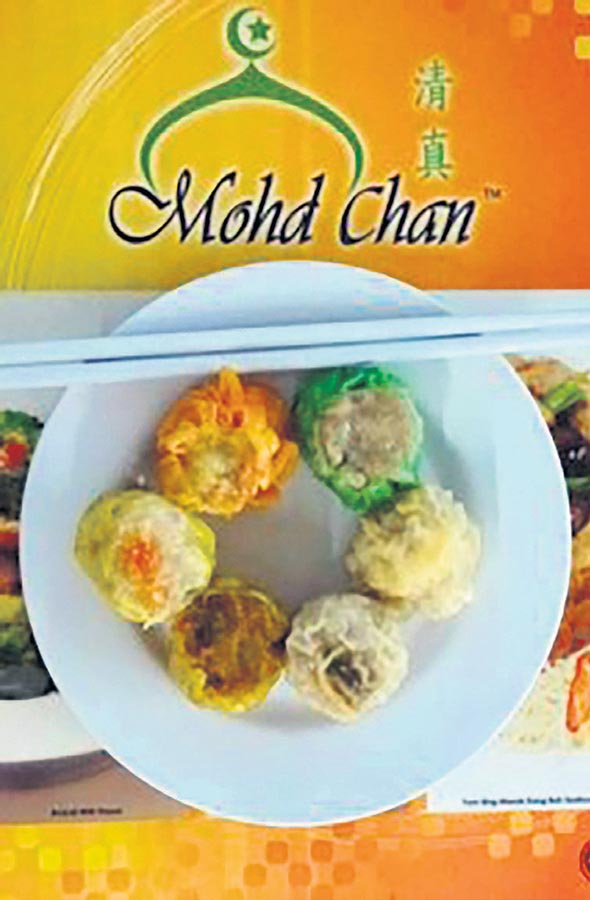

Over the last decade, there have been mushrooming restaurants run by Chinese converts, including Mohammad Chow Kitchen, Mohammad Chan Restaurant, Sharin Low Restaurant, Homst Restaurant, Adam Lai Restaurant, Chef Amman Teoh Restaurant, and more. Most restaurants use the owners’ names as their trademarks – a combination of an Islamic name with a Chinese surname to vividly manifest both their ‘Chineseness’ and ‘Muslimness.’ Two of the most popular ones are Sharin Low Restaurant and Mohammad Chan Restaurants. Each of them has many branches across cities in Malaysia. Claiming itself as a family-style seafood restaurant, Sharin Low Restaurant mainly serves Cantonese-style cuisine – from roasted duck to steamed fish, from butter prawn to pepper tofu. The restaurant’s interior and exterior designs are vividly red and green, with decorations such as Chinese Islamic calligraphy. Mohd Chan Restaurant offers a much more extensive menu, which includes everything from roasted duck to wanton noodle, dim sum to dumpling soup, Cantonese-style cuisine to local fusion. It also serves some ‘non-Chinese’ dishes, such as Indian chicken curry and Malay sambal fish.

Fig. 3: Al-Amber Restaurant (Photo by the author, 2019)

Besides restaurants run by Chinese converts, many Hui migrants from China have also opened restaurants in Malaysia, making Lanzhou lamien a popular dish. Hui involvement in the restaurant business is crucial to both their economic survival and the maintenance of their collective identity. Overall, there are at least four different categories of Hui restaurants. The first is a home-based private restaurant that primarily serves Hui Muslims living in Malaysia. The second is a small-scale restaurant, mainly run by a student-turned-businessperson. The third type is a larger-scale chain restaurant, mainly run by Hui migrants with some food business experience in China. Two examples are Salam Noodle and Chinese Muslim Authentic Heritage Pulled Noodle Restaurant, both of which now have multiple branches in Malaysia. Finally, the fourth type comprises local branches of Hui restaurant chains based in China that are expanding their business overseas, such as Al-Amber Restaurant and Qing Fang Restaurant (closed down during the pandemic).

Established in 2015, Al-Amber in Kuala Lumpur claims it serves “Silk Road” Muslim cuisine, referring to halal Chinese cuisine from the northern parts of China. Today, there are three branches of Al-Amber in Malaysia. In 2019, Al-Amber partnered with Air Asia to promote Lanzhou – the airline’s new destination – by highlighting its signature dish, Lanzhou hand-pulled noodle. While claiming to serve “authentic Muslim cuisine from China,” some of these restaurants also include new cuisines and adapt local Malaysian flavours in their menu. For example, during Chinese New Year, Al-Amber serves Yeesang, a popular local Chinese festive dish. The food menu of another establishment – Chinese Muslim Authentic Heritage Pulled Noodle Restaurant – also exemplifies such adaption. Besides serving ‘authentic’ dishes such as Lanzhou noodle, Ziran mutton, Xinjiang lamb skewers, and potato beef rice bowl, it also creates localized fusion dishes such as golden curry mee tarik and fried mee tarik.

Fig. 4: Sharin Low Restaurant (Photo by the author, 2013)

Sites of halal consumption

Many Chinese and Hui Muslim restaurants are located in middle-class Muslim neighbourhoods, such as Bangi, Shah Alam, Kota Damansara, and Taman Tun Dr Ismail. The owner of Sharin Low restaurant shares with me the key reason behind the success of his business: “There are many middle-class Malay now. They have money to spend. They want to eat authentic and good Chinese food […] Most of the chefs in our restaurants are Chinese. We want to make sure our food taste like real Chinese food, even without using pork and lard.” Indeed, there are increasing demands for cultural diversity within the Islamic framework among segments of urban middle-class Malay Muslims. The popularity of Chinese-style mosques, Chinese Islamic calligraphy, Muslim tours to China, and Chinese halal food reflects many Malay Muslims favoring cultural diversity, yet this does not necessarily support religious pluralism. Instead of seeing Islam as a ‘Malay religion,’ they view Islam as a religion for all humankind. Therefore, appreciating Chinese culture acknowledges the universality of Islam and becomes their subtle way of preaching Islam among non-Muslim Chinese Malaysians.

Indeed, these restaurants are sites of culinary dakwah. Both Sharin Low Restaurant and Mohd Chan Restaurant run Chinese New Year celebrations. They serve free Chinese halal food to the public. They host cultural performances like lion dances and maintain information booths with booklets on Islam in Chinese and English. As Sharin Low told me, “Chinese like to eat, and that is why we think that food can be an effective medium of dakwah.” With the tagline “Islam for all – We create, we educate, we provide,” the owner of C.A.T. Wok Street Food Restaurant has initiated a project called “Dakwah through Food.” Some Hui migrants also cited religious consideration for doing business in Malaysia. For example, Yahya Liu, who runs Salam Noodles Restaurant, explained to me why he left China and moved to Malaysia: “In China, our restaurant in Shenzhen relied on non-Muslim customers, and we had to serve alcoholic drinks. The money we thus earned is not halal […] My brother and I decided to move to Malaysia, as it is a Muslim-majority country, and we can sustain our business without serving the alcoholic drink. Malaysia is also a better place for us to learn and to practice Islam.”

Not surprisingly, many Chinese and Hui restaurants owners perceive their restaurants as places that foster cultural interaction and social inclusion, bringing together Malaysians and non-Malaysians regardless of ethnicity and religious affiliation. In some ways, these restaurants resemble other eating places such as kopitiam (Chinese coffee house) and mamak stalls (Indian Muslim eateries), functioning as sites where people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds get together. However, as I observed, many of the customers in Hui and Chinese Muslim restaurants are Malay and Chinese Muslims. In addition, there has been increasing pressure by religious autorities for these restaurants (especially some kopitiam owned by non-Muslim Chinese) to apply for official halal certification in recent years. Many Hui and Chinese Muslim restaurants have the official halal logo, but some do not. Some owners believe that the naming of the restaurant – using an Islamic name or clearly stating it is a Chinese Muslim restaurant – is enough to convince Muslim consumers that the foods they serve are halal.

Fig. 5: Mohammad Chan Restaurant (Photo by the author, 2013)

From dimsum to roasted duck, from Lanzhou lamien to Xinjiang lamb skewers, Chinese halal foods have gained more popularity among Malay Muslims in Malaysia, indicating consumers’ quests for multicultural yet halal consumption. With the increasing number of Hui migrants and Chinese converts who prefer to maintain their identity, such demands have led to the mushrooming of Hui and Chinese Muslim restaurants. Some restaurant owners also see their restaurants as sites of culinary dakwah, suggesting food as a subtle way to preach Islam among non-Muslims. Such culinary changes reflect a broader trend of Muslim consumption: valuing cultural diversity while prioritizing Islamic principles. It is a trend in which urban space, market forces, and religious observances intersect.

Hew Wai Weng is a research fellow at the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies, National University of Malaysia (IKMAS, UKM). He is the author of Chinese Ways of Being Muslim: Negotiating Ethnicity and Religiosity in Indonesia (NIAS Press, 2018). E-mail: hewwaiweng@ukm.edu.my