China’s long-term Pacific ecological footprint

As well as exercising the minds of policymakers and politicians, China’s increasing role in Pacific affairs is generating considerable scholarly attention. Much of it centres on security issues as well as the PRC’s access to resources and commodities.

Little acknowledged—and little understood—is China’s long-term role in the Pacific. The project ‘Making China’s Pacific: Markets, Migration and Environmental Change in the Pacific, 1790s-1920s’ challenges the presentism of policymakers and politicians. It demonstrates the key role played by China’s market demand and exploitation of new resources in the Pacific. In doing so, it reveals China’s considerable ecological footprint and role in stimulating Euro-American exploitation of a range of Pacific resources for Chinese markets since the late 18th century.

Based at Victoria University of Wellington’s Centre for Science in Society, under Associate Professor James Beattie’s leadership, the project draws in colleagues from Sun Yat-sen University, including Associate Professor FEI Sheng. It utilises archives on the Pacific, from China, Australia and New Zealand. The project’s originality lies in its trans-Pacific dimension and in its emphasis on the environmental history of the overseas Chinese, a group largely ignored by both Pacific historians and historians of China.

Voracious demand for luxury goods in late-eighteenth-century Qing China, combined with a balance-of-payments deficit with Europe, pushed Euro-American traders to find goods to sell in China. Australia’s annexation by Britain in 1788 gave the East India Company and other traders a base in the southern Pacific from which to exploit a range of products for the Chinese market. Southern Ocean islands—including those in the Bass Strait area as well as those in and around southern New Zealand—supplied millions of sealskins, leading to the destruction of resources and long-term contact between sealers and local peoples.

Other resource booms emerged elsewhere in the Pacific. In Fiji and later New Guineau, for example, the sea-cucumber trade transformed environments and societies by linking together peoples, resources and markets. In Fiji, traders constructed large drying houses. American-built ones could measure as much as 100-120 feet in length, and 20 feet in width. Foreigners employed as many as 200 people finding sea cucumber, with as many as 100 cutting firewood, and 50 keeping fires burning. 1 Because sea-cucumber’s drying required constantly lit fires, timber consumption rapidly reduced scarce island forest resources.

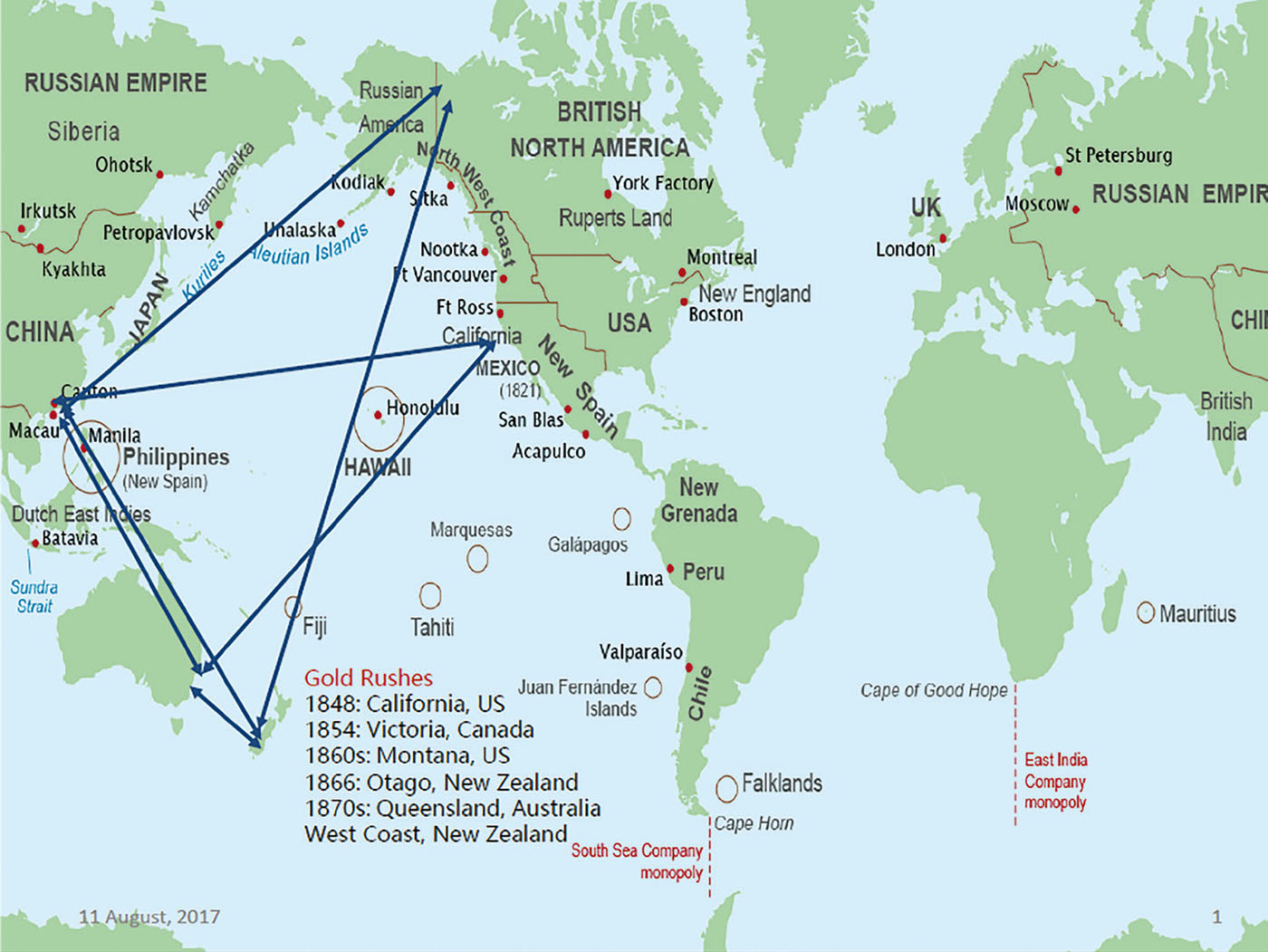

Map of Pacific gold rushes, indicating some routes taken by Chinese miners. Author drawn.

Overall, the trade associated with sealskin, sea cucumber and other enterprises, depleted a variety of resources, leading sometimes to extinctions. Ecological impacts abounded, through the intentional and unintentional introduction of a variety of plants and animals. In these transactions, islanders usually gained new technologies, as well as economic advantages and travel opportunities, but invariably experienced high mortality rates through exposure to new diseases.

Migration, environmental change and the Pacific gold rushes

The next key step in China’s role in the Pacific emerged in the mid-nineteenth century. A combination of British imperialism and a succession of Pacific gold rushes provided opportunities for people from southern China to work overseas. Under the British, Hong Kong became “Asia’s leading Pacific gateway … linking North America and Asia”. By 1939—nearly 100 years after its establishment—an astonishing 6.3 million Chinese had embarked from Hong Kong, with 7.7 million returning to China through the island. 2 Around the Pacific, Chinese worked as goldminers, plantation labourers, railway navvies, market gardeners, and merchants.

The project frames Pacific resource demand, and later Chinese enterprises like market gardening and agricultural investment, as examples of ecocultural networks—interlinked labour flows, migrant connections, and capital systems which transformed Pacific environments, and made nature into commodities. 3 It considers trans-local connections, rather than trans-national ones, to signal that only particular localities in China, the Pacific Islands and New Zealand were connected through Cantonese migration and business networks.

One example of this is the business enterprise of Chew Chong (circa 1828-1920). Arriving in New Zealand in 1866, Chong initially exploited a fungus (Wood Ear) growing in abundance in the forests of northwestern New Zealand that was prized in Chinese cuisine and medicine. Chong arranged to have vast quantities of the fungus dried locally and then shipped to Chinese consumers in Sydney and Qing China. Other Chinese merchants also took part in the enterprise, and from 1880 to 1920 New Zealand fungus exports reaped £401,551. While still sending fungus offshore, Chew Chong invested funds from this enterprise and his trading stores into pioneering the dairy industry in southern Taranaki. He bought the latest equipment, innovated several designs himself, and came up with the concept of share-milking.

In sum, Chinese resource demand and then Chinese people contributed to a great acceleration of environmental change in the seas and countries of the nineteenth-century Pacific. This project is one that gives back Chinese individuals their agency, and places them back into the narrative of the Pacific, its exploitation and integration. Their story is one that politicians and policymakers need to hear when they assess contemporary China’s activities and resource use in the Pacific.

James Beattie, an environmental historian, is an Associate Professor at The Centre for Science in Society, Victoria University of Wellington and Senior Research Fellow, History Department, University of Johannesburg. He has written 12 books and numerous articles on topics related to environment, gardens, art, and ecological transformation James.beattie@vuw.ac.nz; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDXkVrtyhxY