‘Changing the World’? Socialist Realism and Art in the Asia-Pacific

In 1934 Maxim Gorky explained that the role of art was to “change the world.” 1 According to him and Joseph Stalin, the art movement to do this was “socialist in content and realist in style,” an easy mantra that immediately needs further qualification. The Russians themselves, including the proverbially hardline Andrei Zhdanov, insisted on it being a style of emotion and feeling. However, neither the Soviets nor those in power in Asia who wrote about art, particularly Mao Zedong and Kim Il-sung, were specific about what they wanted artists to create – as long as it had political purpose. Their rare comment on specific style was to express their dislike of the European ‘isms’ of the early 20th century, particularly cubism and futurism, which they saw as “the decay of painting.” 2 Based on my new book, this article explores the impact of Socialist Realism throughout the Asia Pacific over the last 100 years.

The art

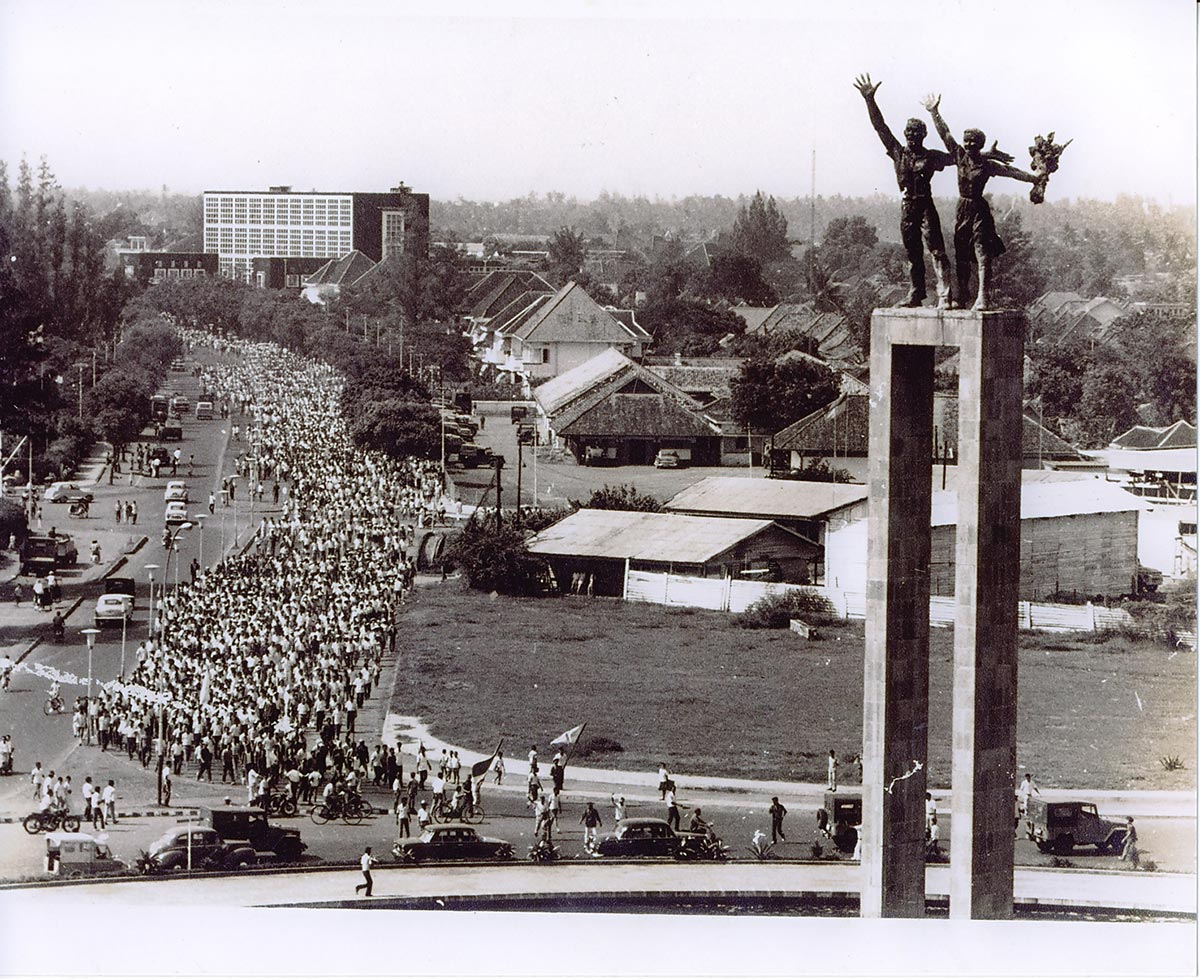

The art made under this rubric in both the USSR and the Asia-Pacific was as varied as the cultures and contexts involved. Vera Mukhina’s (1889-1953) sculpture shown in Paris in 1937 of the Worker and Kolkhoz Woman – which Picasso memorably admired, saying “how beautiful the Soviet giants are against the lilac Parisian sky” 3 – was emulated by Javanese artists commissioned by Sukarno to stand as symbols of future promise at key sites in his new splendid capital. The works were grand, heroic, and sleek, with athletic young people simply dressed looking outwards with great confidence [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1: Henk Nangtung (1921-91) and Edhi Sunarso (1932-2016), Welcome Monument, 1962, bronze, 6 m h, Jalan Thamrin, Jakarta. (Photo: IVAA Collection, Yogyakarta)

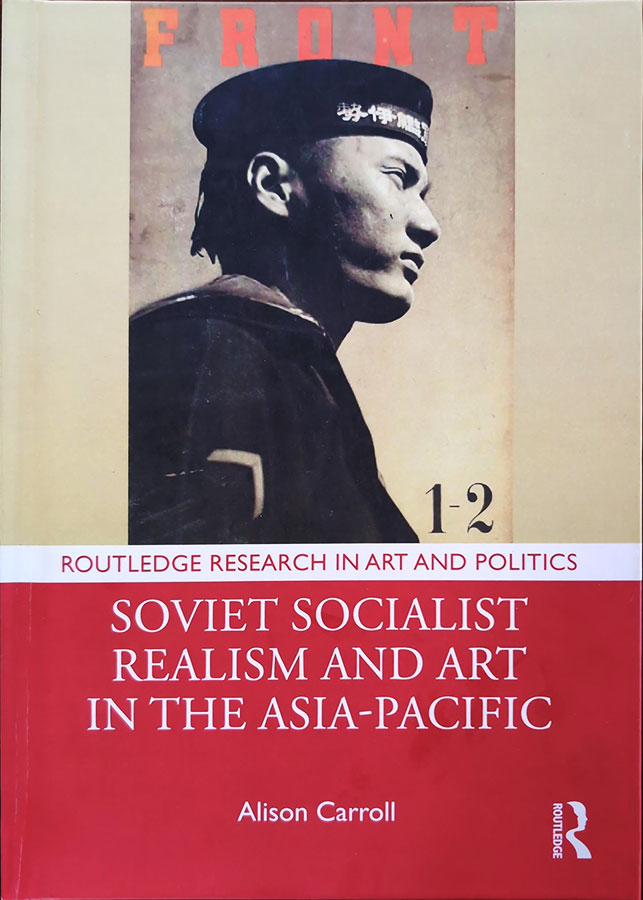

The dramatic graphic forms of Aleksandr Rodchenko [Fig. 2] and El Lissitzky (1890-1941) particularly were admired and followed by Japanese designers creating masterful designs to support their new East Asia Prosperity Zone in the 1940s. They had studied from the Soviet models and created large-scale duotones of collaged imagery, bled edges, simple flat colours, and sharp, angled lines, with a variety of sophisticated type for texts spread across images still memorable today [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3: Cover of Soviet Socialist Realism and Art in the Asia-Pacific (Routledge, 2025). Cover image is the Japanese magazine FRONT, No. 1-2, 1942, Navy Issue, lithograph, 41.5 x 19 cm.

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, when poster-making took on such importance, groups from the army, amongst many, used the stylised, simplified Soviet graphic example to make some of the iconic images of the period [Fig. 4].

Fig. 4: The 3 July and 24 July proclamations are Chairman Mao's great strategic plans! Unite to strike surely, accurately and relentlessly at the handful of class enemies, 1968, lithograph,105.5 x 75.5 cm. Tianjin Fine Arts Publishing House. Landsberger Collection, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

The grand history tableaux painted by the Soviets, using the whole apparatus of European academic technique, were taken up by young Chinese artists to similarly acclaim their own new revolutionary history. Many of the Chinese paintings were specifically made for the new (Soviet-inspired) Museum of Chinese History (now National Museum), where they are still in pride of place and are often of greater visual import than their predecessors in the USSR. Shen Jiawei’s Standing Guard for our Great Motherland of 1974 is one example made at the height of the Cultural Revolution to extol the courage and strength of the young border guards [Fig. 5]. Yet it also reflects the composition and intention of the much more prosaic 1938 painting of Stalin and Voroshilov at the Kremlin by Russian Academician Aleksandr Gerasimov (1881-1963). 4 Another example is Lin Gang’s (b. 1924) large brush and ink painting of a young girl praised by Mao Zedong, emulating the Vasili Efanov (1900-78) image of a similar event with Stalin. Both works, composed of dignitaries arrayed on a shallow picture plane, are exceptional for their celebration of young women in such paternalistic cultures.

Fig. 5: Shen Jiawei (b. 1948), Standing Guard for our Great Motherland, 1974, oil on canvas, 189 x 158 cm. Coll: Long Museum, Shanghai. (Image courtesy of the artist)

This is the imagery produced, but behind it is an equally important story about the role of art in society. The Soviets had introduced and implemented, top down, the idea that art should be accessible to everyone. We can all be artists – it is our right. The idea had great impact in the Asia-Pacific, with cultural ministries created and art education made open for everyone, including for ‘soldiers, workers and farmers.’ Museums were built to show art, assemblies were held, and multiple publications were circulated.

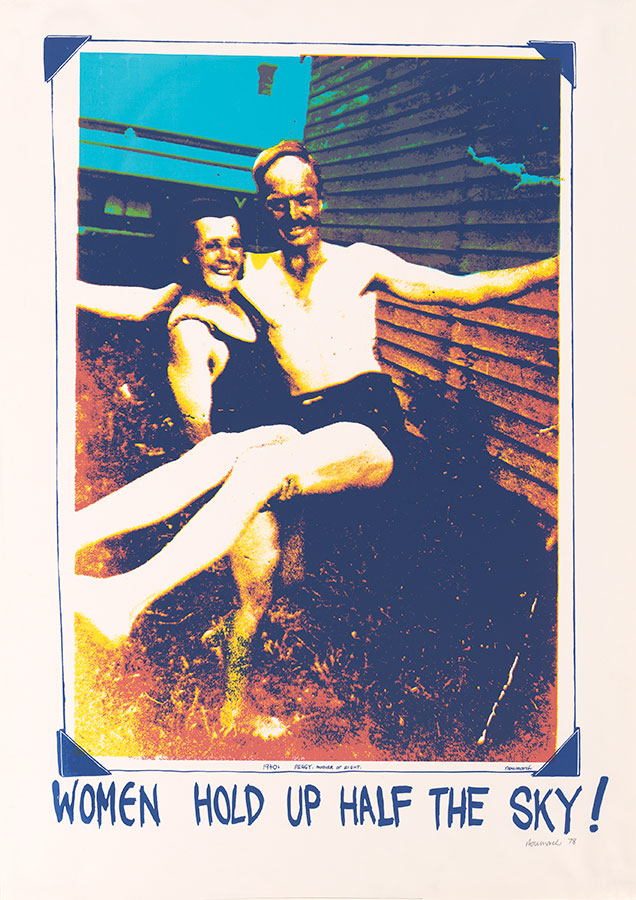

Australia prides itself on its egalitarian spirit, with its ‘working man’ ethos epitomised by the strong Trade Union movement. In the early 1970s the Whitlam government and its official body, the Australia Council for the Arts, created a new Community Arts Board, which they called “a world leader in having dedicated and unbroken funding to support community arts.” It was defined by “the creative processes and relationships developed with community” rather than the ‘artistic excellence’ of the outcome. 5 Ann Newmarch’s work Women Hold up Half the Sky made at this time recognises the new thinking reflected in the Maoist phrase with a typically disrespectful humour. It is a photo of her aunt Peg lifting her husband on holiday [Fig. 6].

Fig. 6: Ann Newmarch (1945-2022), Women Hold Up Half the Sky!, 1978, screenprint, 80 x 56 cm. Coll: National Gallery of Australia. (Image courtesy artist’s estate)

As is often the way, many of the artists in Asia who successfully adopted and adapted this new style did it in accord with local traditions. In China, millions of posters reflected both folk and literati traditions in the use of fluid lines on paper and in the easy combination of image and text. In Vietnam, quiet watercolours in support of the new regime paid homage to their influential French experience. The publications designed in Tokyo to support the WWII-era militarist regime reflected centuries of restrained linear and planar mastery of the ukiyo-e masters. The dramatic, complex, highly competent historical imagery created in Manila in support of the church and the ilustrado (ruling) class was applied by artists like Pablo Baens Santos [Fig.7] and collectives like Sanggawa (est.1994) to extoll the new political order. In Indonesia, the strength of artistic collectives making political comment reflected local understandings of gotong royong, or working together, 6 and in Australia the ubiquity of community arts officers employed by local government to encourage ‘art for the people’ was welcomed by a culture which decried class distinctions – at least officially.

Fig. 7: Pablo Baens Santos (b. 1943). Manifesto,1985-87, oil on canvas, 157.66 x 254.3 cm. Coll: National Gallery Singapore. (Image courtesy National Heritage Board, Singapore)

Vilification

If this work has been significant, why is it treated so poorly? Is it purely because of the context of political repression (and worse) in many of the places discussed here? There are long answers about equivalences of evil, but perhaps the best is to say that art extends beyond the context of its creation, although understanding that context is important. In the end, the work stands for itself.

Nevertheless, this is a movement that almost everyone who knows global art history disparages with simple judgements. Socialist Realism is still frequently dismissed as soulless, unimaginative, repressed, and kitsch.

The Cold War provided the context for Western art historiography to discredit Socialist Realism in the ‘First World’ and to ultimately spread that disdain to the Asia-Pacific adaptations. An essay by American critic Clement Greenberg in 1939 was very influential. 7 First, Greenberg raises the idea of Western connoisseurship in evaluating good and bad taste, positioning Socialist Realism as ‘bad taste’ or kitsch. Second, the Enlightenment centrality of the single elite genius is contrasted with Socialist Realism’s apparent disregard for individualistic creative processes. Third, the essay discredits the related idea of popular (mass) visual art and Socialist Realism’s focus on mass popularity. Fourth, any role of the state in art’s creation is critiqued, specifically the paramount role of the state in Socialist Realism and its apparently deleterious effect on the quality of the work produced. This is obviously all either untrue, or else so loaded that the arguments don’t fly. Michelanglo worked for the State; Van Gogh is popular; and the last Documenta exhibiton in Kassel celebrated the work of collectives today. Finally, the idea of inherent elite good taste is a throw-back to, we hope, long-gone class distinctions – that you need to be wealthy or of a higher class to appreciate art.

A corollory of this is the often disparaging use of the tag ‘propaganda’ in association with Socialist Realism. The term took on a negative meaning in the West after World War I and implies that the art had no value beyond being a tool of Communist politics. In saying this it is salient to remember Mao’s words in his Yanan talk in 1942: that artists must put “political criteria first and artistic criteria second” but “works of art which lack artistic quality have no force, however progressive they are politically.” 8

If Socialist Realism had no strength as art, nobody would care, but the style’s spread and impact through the Asia-Pacific highlights that this is not so. Contrary to Western thinking, it was the visual power of this work describing an idealised new world that has stirred countless millions through the last century in the Asia-Pacific. One indication of their visual force is that, in China in the 1980s and 1990s, artists used the style satirically in works that gained worldwide notice and admiration.

Today

Is this movement over? The thinking that everyone can and should have access to the arts – whether as practitioner or audience – remains unchallenged in most countries of the region.

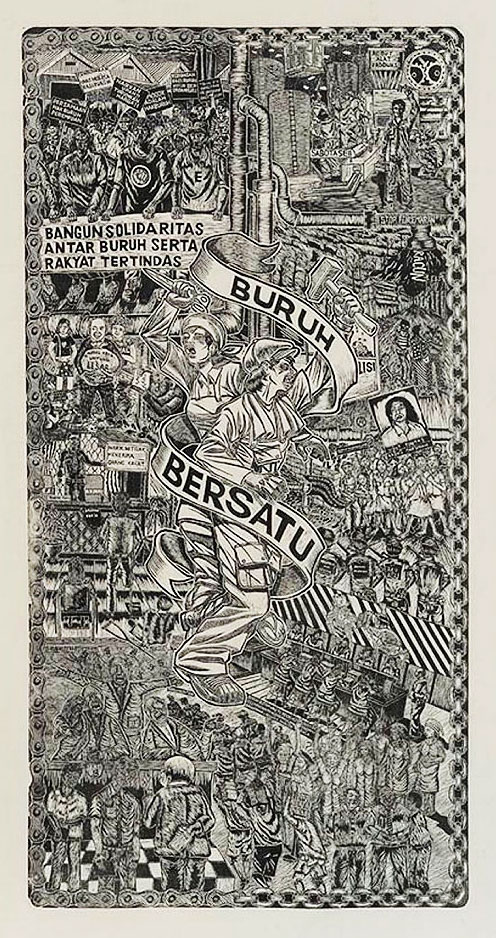

In Indonesia, despite persistent sensitivity towards ‘communist’ thinking, collectives like Taring Padi continue to actively address political issues in imagery that has spread to Timor Leste and East Malaysian artist groups. Examples are the series of woodcuts like The Workers Unite now in Queensland Art Gallery collection, with the subheading translating to “build solidarity between the rich and the oppressed people” [Fig. 8].

Fig. 8: Taring Padi (collective est. 1998), The Workers Unite, 2003, woodcut print on canvas, 242 x 122cm. Coll: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane.

Communist Asia continues to make posters in the heroic style, as sometimes occurs in leftist states such as Kerala in India. In China, artists like Wang Guangyi (b. 1957) have continued to make large paintings in the stylistic grand manner of the Cultural Revolution, like his Art and Politics now at Hong Kong’s M+ museum. Shen Jiawei, who painted the Border Guards 50 years ago, has recently completed an enormous, complex painting depicting the history of Communism. 9 The artist is critical of much of Communism’s past but pays tribute to its importance and impact, especially on the arts. 10

Particularly intriguing, the 100th anniversary celebrations of the CCP in Beijing in 2021 included a performative recreation of the same historical, heroic scene on the National Monument in Tiananmen Square sculpted in the 1950s. The early work was made in the flush of belief in the new Republic. The recent tableau was created in the footsteps of the pictorial mockery and satire of the 1990s but here there is no irony in sight. 11

Socialist Realism in the Asia-Pacific needs greater recognition for the lasting visual imagery of keenly felt idealism and challenge created under its umbrella. That so many memorable and moving works of art throughout the region owe so much to the ideology and practice is testament to its significance.

Alison Carroll is a Senior Research Fellow at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. She has worked as a curator, writer, academic, and administrator, focussing on Asian art of the last 100 years. Her new book is Soviet Socialist Realism and Art in the Asia-Pacific (Routledge, 2025). Email: alison.m.carroll@gmail.com.