Covid-19 in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia was among the first regions that had to battle the COVID-19 virus originating from Wuhan, China. Given the heterogeneity in the socio-economic conditions in the region, how did and will the Southeast Asian countries fare after the pandemic? This is the overarching question posed by this erudite volume that brings together an impressive array of social scientists from multiple disciplines emanating from academic institutions, think tanks, and civil society organizations. The volume is stupendous in the breadth and depth of issues being addressed, ranging from urbanization, the environment, people’s movement, collective action, and local community. It will stand as an authoritative volume that many – and anyone – with an interest in Southeast Asia will enthusiastically consult in the future.

The contributors uniformly treat COVID-19 as a critical juncture upon which they reflect how the issues examined maybe affected as a result of the pandemic. The volume is divided into three sections. Section One looks at urbanization, digital infrastructures, economies, and the environment; Section Two examines migration, mobilities, and cross-border issues; and the final section focuses on collective action, communities, and mutual action.

The contributors in Section One describe the rapid adoption of digital technologies to contain the virus as a double-edged sword that helps with contact tracing and connecting communities on the one hand, and also enhances state surveillance and empowers the state on the other hand. The pernicious effects of digital technologies are by no means exclusive to Southeast Asia; however, the deficiency in democratic institutions in parts of the region has allowed some governments to use those technologies to enhance their power to the disadvantage of the societies. Uneven access to technologies can also create inequitable opportunities across society, thereby raising concerns about the utility of digital technologies in times of crisis.

The first section then turns its attention to sectoral impacts of the pandemic on real estate, business process outsourcing, and garment industries. The common thread is that the pandemic has laid bare that the precarity of these industries – dependence of the property market in Malaysia on mobility of international investors, and more generally the exploitative relationship between global capitalists and manufacturing industries in the region – have exacerbated their detrimental effects on the marginalized in the societies. The remaining chapters in the section examine the impacts of the pandemic on labor relations and environmental conditions in the region.

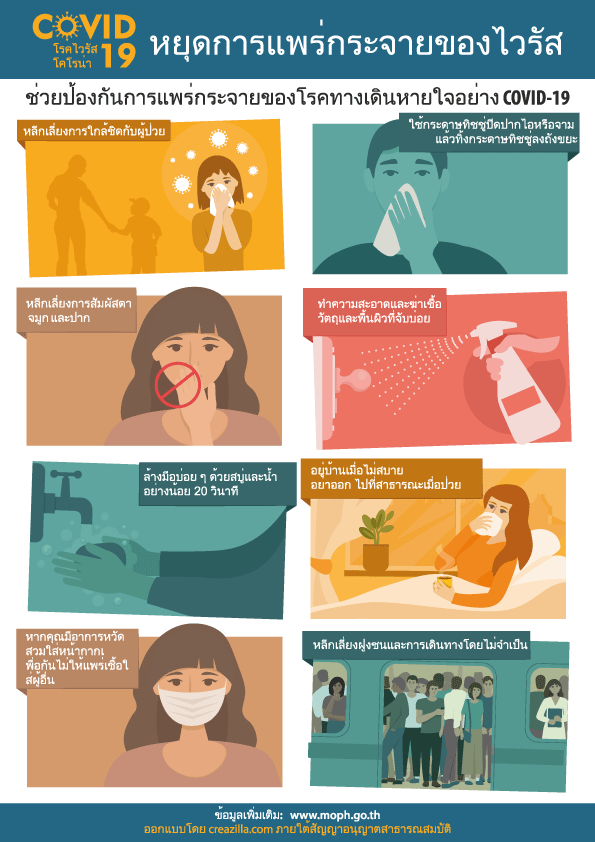

Thai public health poster, courtesy of Wikimedia.

The seven chapters in the Section Two take a critical view of the impacts of the pandemic on labor mobility, including the plight of the migrant workforce in Singapore and Malaysia, repatriated Filipino workers, and those in working in healthcare sectors overseas. The common thread across these cases is the precarity of this workforce pre-pandemic: they were the underbelly of the societies, and they were easily forgotten. The government’s pandemic control measures took extra tolls on these workers, who appear invisible to the authorities (due to their informal status), whose pandemic-related immobility has affected their income, and/or who were caught in between borders because of the pandemic. Taking a case study approach, this section offers detailed analyses of the precarity of the low-end – and often foreign – labor force that is hardest hit by the pandemic.

In Section Three, the eight chapters examine various grassroots initiatives that support communities to contain the virus through the lens of collective action and mutual aid. These chapters give primacy to the people of Southeast Asia to illustrate how they can shape a better outcome when they come together – from neighborhood food-sharing and gotong royong in Indonesia to “happiness-sharing pantries” in Thailand and online collective actions.

These chapters are very fitting to end a voluminous book on Southeast Asia, which prides itself on being a heterogenous region with a multiplicity of ethnic groups, cultures, and religious beliefs. Despite such wide-ranging diversity, socio-economic issues that surfaced due to the pandemic are beyond the reach of the state – and are still best tackled by the grassroots communities.

Overall, this is an extremely impressive collection of essays that takes seriously the diversity of the region and offers thoughtful reflections on what the pandemic means for the cities, environment, economies, institutions, and people of Southeast Asia. It would be – and should be – widely read by not only area specialists, but also urban planners, geographers, and other social scientists interested in how societies evolve after a profound critical juncture.