Writing Letters for Soldiers: Literate Girls’ Epistolary Service in Wartime China

Writing letters for seniors was a common theme in epistolary primers for young students in the first half of 20th-century China. These popular instructional models capture the immediate experience of many literate boys and girls of the day, who contributed to their families and communities through their voluntary epistolary service. Indeed, the existing real-life stories of these warm-hearted young authors demonstrate the agency of youth, challenging mainstream narratives that depict children as immature or incapable. 1 The extensive biographical literature and records I have collected for my ongoing project about letter-writing children in modern China suggests that many young students, especially girls, assumed the task of writing letters for wounded soldiers during China’s War of Resistance against Japan (1937–1945) and the Chinese Civil War (1945–1949). Although some letter-writing stories have been rediscovered by scholars to highlight Chinese women’s wartime contribution, 2 most participants’ accounts of their epistolary service remain largely unknown to the public. By uncovering some of these long-hidden stories, this article highlights the letter-writing girls in wartime China to further illustrate how epistolary literacy elevated Chinese girls’ roles in broader sociopolitical communities and enabled them to become powerful subjects.

Liu Taozhen 劉桃貞 (1919–?) was one of these letter-writing girls, as recorded in her later essay. 3 , in Qinli kangzhan: Beijing jiaoyujie laotongzhi kangzhan huiyilu親歷抗戰:北京教育界老同志抗戰回憶錄 [Personal experiences in the Anti-Japanese War: The memoirs of veteran comrades involved in education in Beijing], ed. Zhonggong Beijing shiwei jiaoyu gongzuo weiyuanhui (Beijing: Zhongguo guangbo dianshi chubanshe, 2005), 331–334.] She was a progressive member of the Communist Party-led “Chinese Liberation Pioneers Squad” (Zhonghua minzu jiefang xianfeng dui 中華民族解放先鋒隊) from Sanyuan 三原 Female Middle School (Shaanxi Province). In 1938, during the early stage of the War of Resistance against Japan, Liu worked together with her teachers and other students to raise money and sew quilts and clothing for wounded soldiers. The group also assisted wounded soldiers with writing letters home to their families.

One 19-year-old soldier was injured so badly that none of the students initially volunteered to write a letter to his family. However, Liu Taozhen stepped forward to apologize for not attending to his needs earlier, and she eventually helped him write two letters: one to his parents and another to his new bride. The latter was especially tragic: the soldier urged Liu to help him convince his wife to find another healthy husband because of his grave injuries during the war. Liu was initially concerned about her ability to complete such a challenging letter, but since she could not bear the disappointed look of a helpless soldier who had lost his arms and legs, she nevertheless agreed. She listened to him with respect and patience, as a professional scribe would do to his customer in the marketplace. To avoid breaking his bride’s heart, they decided to hide the brutal fact of his disability by fabricating a story that he had joined the “Death Squad,” which positioned him in extreme danger at all times. Liu read her draft aloud to confirm that her letter conveyed his “genuine feeling” (zhenqing 真情) and communicated his request for their breakup in the gentlest language. She perceived this letter as more of a literary creation because of its sophisticated rhetoric of affection and devotion. She might have also achieved a sense of pride from the compliments she received from the soldier, which she vividly recalled many years later: “You are among the school children (xuesheng wa 學生娃) but act like a fortune-telling master (suangua xiansheng 算卦先生), holding the power to fully draw out what is really in a person’s heart. Your teachers are really good at educating students.” By comparing Liu to a fortune teller, a category of professional scribes from which Liu drew inspiration, the soldier acknowledged her knack for written communication and her professional ethics.

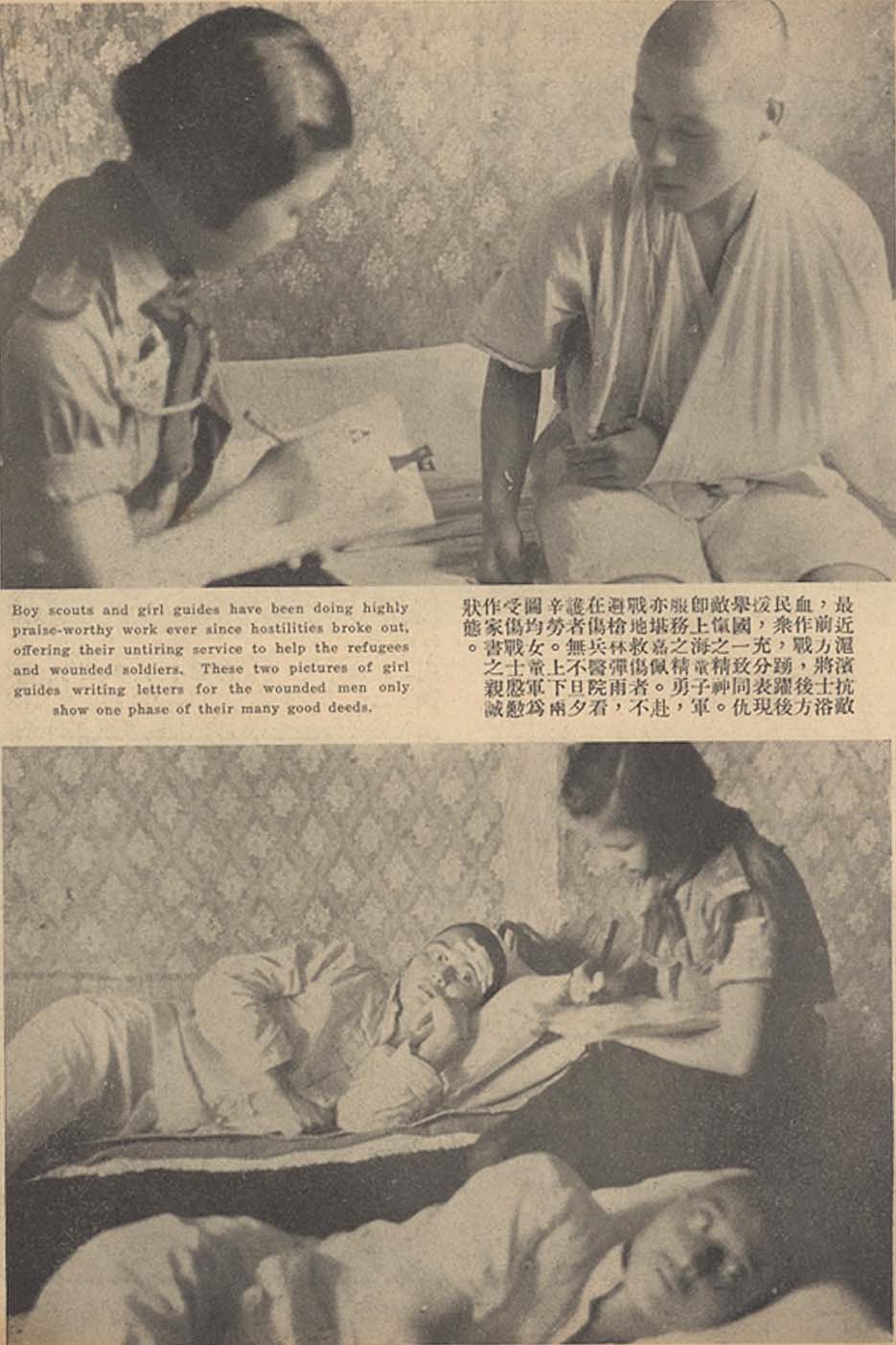

Fig. 1: Bilingual descriptions of Chinese girl guides’ epistolary service for wounded soldiers in a hospital of Shanghai from The War Pictorial 戰事畫刊 (dated 1937). These letter-writing girls were deemed admirable by the general public for their courageous service and portrayed as exemplars of civilians. Photographs of such care were not unusual in wartime magazines to demonstrate the spirit of the whole country passionately united against Japan. (Image courtesy of Shanghai Library).

The second story of comforting injured soldiers took place in Nanchang (Jiangxi Province) during the Chinese Civil War (ca. 1948). Lin Mianqian 林緬芊 published an article about her letter-writing experience in hospitals in the Modern Children Magazine 新兒童. 4 , Modern Children Magazine 22.3 (1949): 36–37.] She was among 30 female students from three local girls’ schools whose primary objective upon arriving was to help the soldiers write letters home to their families.

Lin started her journey with excitement, but she was soon saddened by the inhospitable conditions these soldiers suffered. Three of the ten wounded soldiers whom Lin helped left a strong impression on her. The first young soldier from Henan sought to write a letter home to his mother, who was desperate for his pay and provisions to make ends meet. However, he was so upset that Lin could not understand his accent that he lost his temper. Instead of feeling annoyed or flustered, Lin showed sympathy for his physical pain and emotional distress, apologizing to him and asking a translator for help to finish the letter. Another soldier from Guangdong proclaimed that he was also in need of help; nevertheless, he complained that he was not able to communicate with the visiting students since he did not understand the Mandarin they spoke. Luckily, Lin understood Cantonese and willingly took over the task of helping this soldier, who had not returned home in three years, compose a letter to his uncle requesting medicine. Both soldiers seemed satisfied with Lin’s efforts of turning their vernacular language into written words, as they expressed their gratitude to her in the end.

Fig. 2: As an earnest reader of the Modern Children Magazine, Lin Mianqian sent her photograph (dated 1949) to the magazine for publication. (Image courtesy of Shanghai Library).

The third soldier, whom Lin deemed “eccentric,” wanted Lin to ask his father to pick him up from the troops because he was uncomfortable with what he described as the troop’s “dark side.” Despite this request, Lin heeded her teacher’s request that negative comments about the war or battlefield conditions should be avoided in letters. She thus took the liberty of excluding the soldier’s disturbing description once she confirmed that he was illiterate. Lin felt an enormous sense of unease for censoring this part of the letter, especially because he seemed to place great trust and expectations on her. Considering Nanchang, where Lin resided, was under the administration of the Nationalist government when she volunteered her services as a letter writer, it is likely that the soldiers Lin helped were enrolled in the Nationalist Forces, and she was politically sensitive about the low morale of the troops fighting for the Kuomingtang. She concluded her journey by observing that Chinese soldiers endured the most hardship of any people in the world and hoped that the Nationalist government would increase their remuneration.

Stories of girls writing letters for wounded soldiers across the country abound in contemporaries’ memoirs, essays, diaries, photos, and other forms of documentation. These stories, either narrated by girls themselves or recorded by other witnesses, demonstrate the important political and emotional role of young female letter writers in wartime China, which has often been critically overlooked. As Nicole Barnes suggests, educated young women’s wartime “emotional labor,” such as writing letters for soldiers, created an intimate connection between two populations who would otherwise have had few opportunities to meet and share personal details: female students of the urban middle class and male soldiers from poor villages. 5 Although few sources suggest that these schoolgirls and wounded soldiers continued their conversations after they parted, the heartbreaking scenes during their epistolary service must have been indelibly imprinted on the minds of most girls. The task of fostering communication between soldiers in the field and their families from afar presumably reshaped the sociopolitical consciousness of literate girls, especially those from affluent families. More notably, the two letter-writing girls in the aforementioned stories, Liu Taozhen and Lin Mianqian, showed their determination to gain recognition for these underprivileged soldiers. This determination prompted them to overcome various difficulties, such as dialect barriers, fears of soldiers’ bloody bodies, and soldiers’ quick tempers. The acquisition of epistolary literacy actively empowered these school girls and gave them confidence and courage in their ongoing endeavour to serve their country.

Cai Danni is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in the History Department of Hangzhou Normal University, Zhejiang, China. This research is sponsored by the Program of Philosophy and Social Science Fund of Zhejiang Province (No. 24NDQN006YB). Email: danni.cai@hznu.edu.cn