A worldwide hunt for Dutch sources on early-modern India and Sri Lanka

<p>The project title ‘Dutch sources on South Asia’ perhaps evokes an idea of archives and libraries within the Netherlands, but many such sources can actually be found outside the country. In an effort to trace these, Lennart Bes and Gijs Kruijtzer searched collections the world over. The resulting guide adds a new dimension to what we may think of as the Dutch East India Company archive.</p>

In May 1698 a worried official of the VOC, or Dutch East India Company, stationed on India’s south-western Malabar coast (present-day Kerala) wrote the following about the Company’s record administration:

The secretariat has the misfortune that the papers not only must be kept with difficulty from the injuries by the Malabarian air, but, moreover, so many documents of importance have been found damaged or missing among them, that it is a shame [...] because they may often come in useful, even when one least thinks of it. And therefore it is a very bad habit, which also has been in fashion in Malabar for some time, that various papers [...] like extracts from proceedings, memoirs and such [...] have been taken and removed by various people to whom those [papers] relate [...]. And in such a way these papers went missing upon the death or transfer of those people, [while] the office remained devoid and the orders fell into oblivion. 1

These words would prove foretelling in two respects. First, notwithstanding the Dutch official’s warning, many VOC documents kept in Malabar and elsewhere in South Asia did eventually vanish. The local climate, pests, neglect, theft, archival transfers and changing record-keeping practices all contributed to the fact that the records of the Dutch settlements in India and Sri Lanka have only partly survived—unlike the Company’s archives created in the Dutch Republic itself, of which much has remained. The other prophetic element, of which our VOC official could hardly have been aware, concerns his view that these documents “may often come in useful, even when one least thinks of it.” Interestingly, this statement rather accurately sums up the current position of Dutch sources in the historiography of South Asia: despite these materials’ great value, relatively few historians consult them, even though a certain mystique surrounds them among scholarly circles.

South Asian history, Dutch reporters, global collectors

To improve the accessibility of the materials drawn up and collected by people connected to the VOC in the course of their contacts with South Asia, Jos Gommans of Leiden University’s Institute for History launched an initiative to produce a series of archival guides. After joining the project, we (Kruijtzer & Bes) started with a guide to the sources that can be found in the National Archives of the Netherlands in the Hague, which cover the period of the VOC and its successors in South Asia (c. 1600 to 1825). That volume appeared in 2001. We compiled a second volume in 2007, based on similar sources found elsewhere in the Netherlands, which added a new dimension to our understanding of the scope of Dutch engagement with South Asia by listing materials created by Dutch people not in the service of the VOC. These included, for instance, missionaries, scholars, and artists. Rembrandt’s drawings after Indian miniatures are an example. 2

A third and final volume has now also been produced. 3 This volume guides you to sources found in the ‘rest of the world’, and traces as it were the VOC ‘archive’ in the broad postmodern sense of the term. It retains the comprehensive scope of the second volume, but also provides a new perspective on the international life of this archive. It includes both the records that were created ‘nearest’ to the Indo-Dutch interaction and materials that have drifted furthest from their original setting.

Where to begin such a global hunt for ‘Dutch sources’ (which we redefined as documents and flat visual materials produced or acquired by Dutchmen as well as other people connected to the VOC and its immediate successors)? Fortunately, the last fifteen years have seen a great effort to inventory much of the actual archives of the VOC that remain in what used to be the radius of the VOC, namely everywhere east of the Cape of Good Hope. Especially important are the voluminous archives still kept in Chennai, Colombo and Jakarta. These remaining administrations of the Company establishments contain many types of documents not found in archives in the Netherlands. The Dutch records in Colombo strayed no more than a few kilometres from where they were created and those in Chennai were moved only a few hundred miles by the British from their places of creation in the Malabar, Gujarat, Bengal and Coromandel regions. Witness to the interactions between the VOC and South Asia, and created on the spot, these records tell us about events of a more local and daily character, ranging from judicial case files and slave lists to plans of Indian dwellings and palm-leaf letters in South Asian languages.

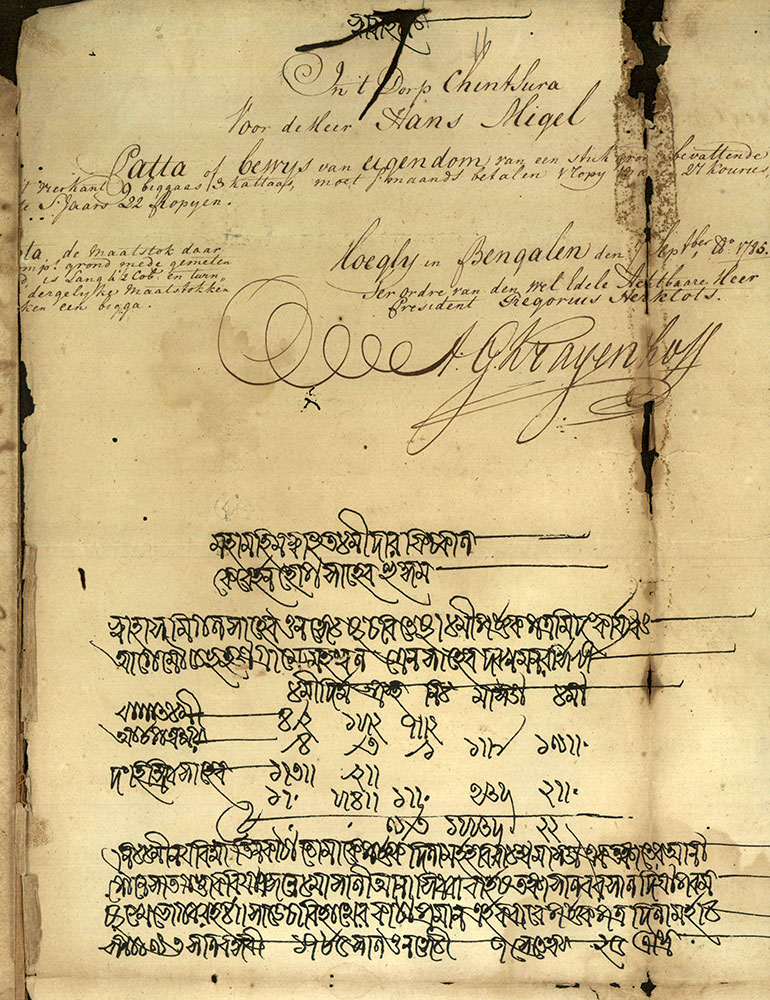

We also found other documents still stored more-or-less locally. First of all a collection of land records relating to the Dutch administration of Chinsura in Bengal, now in the State Archives in Kolkata, and correspondence with local rulers and merchants in and around Cochin, now in the Regional Archives at Ernakulam. We heard reports of VOC documents still in the possession of descendants of people who had conducted business with the Company, but they proved hard to find. Great efforts were, for instance, made by us and local well-wishers to trace a document near Sadras in Tamil Nadu, which had been sighted in the 1990s, but in the end our guide only includes one document held privately in Palakollu in Andhra Pradesh. This contains details of a land grant for the construction of a tank to dye textiles that are interesting from a social history point of view.

Sources contested and neglected

Our findings very much reflect the varying degrees of appreciation accorded in different times and places to sources emanating from the VOC. The history of this appreciation ranges from contestation to neglect. The records that essentially stayed in place largely survived because they were prized by the—in many places British—successors to the VOC, but the ones that strayed often went through extremely complex trajectories. They were requisitioned, sold, stolen, copied and gifted all over the globe.

First of all, there was the struggle for domination of the land and seas of (South) Asia between the various European powers that shaped the operations of the VOC and its European competitors. Many of the ‘Dutch’ materials in Great Britain and France ended up in those countries because they were caught up in a war (such as the Prize Papers in the National Archives in London), or seized from the Dutch on account of their perceived usefulness for the Asian expansion of those countries. The latter is the case especially for some of the VOC materials transferred to Paris during the Napoleonic occupation of the Netherlands, as well as the papers of Isaac Titsingh, over whose inheritance several French ministries laid claim. Napoleon himself stepped in to prevent them from being donated to the British Museum, as Titsingh had intended. The French and English competitors of the Dutch also made numerous copies of Dutch archival materials (including maps), which can still be consulted in Colombo, London and Paris.

Furthermore, for Germany and Central Europe, the Dutch Republic and the VOC functioned very much as a portal to the East. This is reflected by the geographical dispersal of many private papers. First, there are the diaries and travelogues left in their home countries by some of the numerous Germans, Swiss, Poles and Danes who took service with the VOC. Second, some ex-VOC personnel ended up as expert advisors to German and Central European rulers, a case in point being Artus Gijsels, whose papers are now in Karlsruhe. Third, in the Age of Discovery in which the VOC played such a crucial role in the transmission of objects from and knowledge about Asia, scholars and nobles in Central Europe were as interested as any in obtaining such curiosities and information and looked to the Dutch Republic for this purpose. The only surviving items (known to us) from among the extensive scientific manuscripts drawn up and kept by homo universalis and VOC employee Herbert de Jager have turned up in Giessen in Germany, where a university professor seems to have acquired them from the German soldier who took care of De Jager during his final days in Batavia.

The visual materials procured or produced by the Dutch were often treated as rarities, and therefore moved fastest and furthest. Maria Theresia of Austria had agents seek out Indian miniature paintings in the Netherlands, while the Florentine Medici family collected Vingboons’ maps and bird’s-eye views. Many of these visual materials have become works of art only in the modern period, such as the Golkonda-style paintings of Cornelis van den Bogaerde in his Indian setting. He probably commissioned them as souvenirs, but the French artist Raymond Subes scooped them up for his collection in the twentieth century and they have lately found a place in the galleries of Islamic art at The David Collection in Copenhagen.

Altogether, the relevant Dutch sources outside the Netherlands comprise a body of information that stands out for both its massive size and its specific contents, and this third archival guide has grown even thicker than its predecessors. Now that the enormous and highly varied body of Dutch sources worldwide on early-modern South Asia has been described in three archival guides, we hope that scholars agree with the VOC official quoted above that these materials “often come in useful”, and that they will finally be used to their full potential.

Gijs Kruijtzer (gijsbertkruijtzer@gmail.com)

Lennart Bes (l.p.j.bes@hum.leidenuniv.nl)