“Who Wants To Go See France?”: The Vietnamese Experience at the Paris Colonial Exposition 1931

The Paris Colonial Exposition opened its doors on May 6, 1931 in the Vincennes Forest on the outskirts of Paris and ran for six months until November 15. Nicknamed “Lyauteyville” after Marshall Lyautey, its general commissioner, the Exposition was a gigantic, magnificent complex of pavilions representing French overseas colonies from Asia to West Africa. The colonies of other powers such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, and the United States – although not the British Empire – were also exhibited. The event was intended to rekindle the general population’s dwindling interest in, or even hostility towards, the French Empire’s colonial project, which had suffered gravely from the 1929 economic crisis. It was estimated that the Exposition attracted between seven and nine million visitors from around the world. 1

The Colonial Exposition in the pages of Vietnamese-language press

As early as 1927, a number of Vietnamese-language newspapers across the three Vietnamese regions of Tonkin (northern Vietnam), Annam (central Vietnam), and Cochinchina (southern Vietnam) in the Indochinese Union (1887-1954) had started running news reports of “the grandest-ever colonial exposition” in Paris. 2 From 1929 to the end of the Exposition, more than a dozen newspapers and periodicals had run over 100 news items on the Exposition. Most frequently reported were announcements from the colonial government to recruit local artisans and industrialists to bring their trade and workers to the Indochinese pavilions, where they were expected to display, make, and sell a wide range of goods. Such goods included everything from ivory, bronze, and silk embroidery to pictures and children’s toys – products that were “simple yet rich in Vietnamese spirit.” 3 News of Governor-General Pierre Pasquier’s travels and communications with Paris were closely followed as positive signs for Indochina’s participation at the Exposition, as well as for the French government’s support for fiscal projects in the colony. 4 During the preparation period, names of native colonial secretaries were chosen to represent each of the five Indochinese regions at their corresponding pavilion and ethnographic zone, and well-wishing messages were posted to congratulate Vietnamese businessowners and intellectuals selected to participate in the Exposition with a hope that they would enrich Vietnamese creative productions upon their return. 5

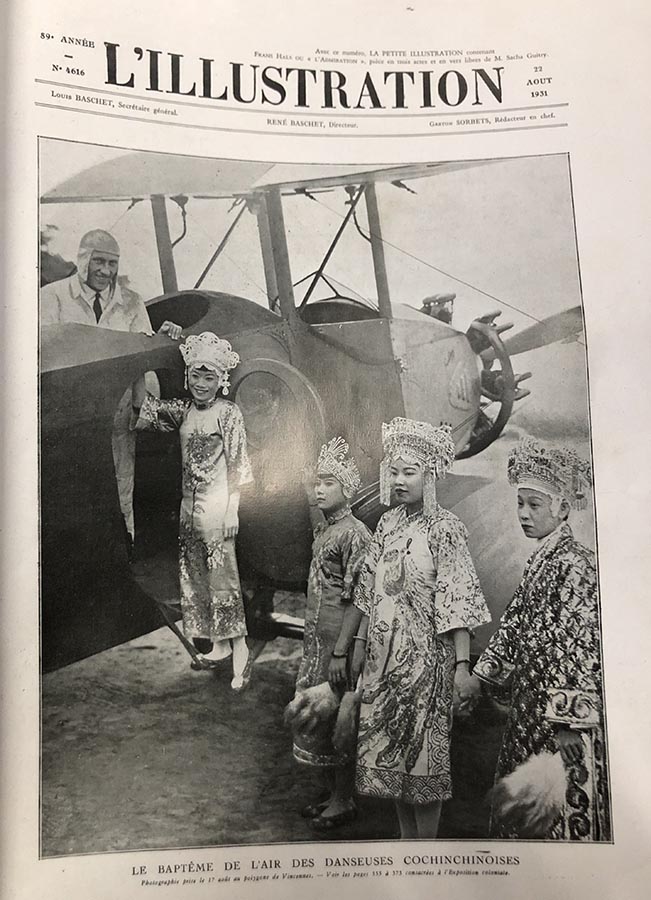

Celebrity performers and sportsmen – who were elected by the colonial government to represent Vietnamese culture and civilisation – were also showered with attention from the press, most notably Gánh hát Phước Cương (Reformed Opera Troupe) and their star performer, singer-actress Năm Phỉ. The troupe frequently ran rehearsal shows to raise funds for their travel to Paris, and they would later travel to Hanoi to re-perform their Exposition show in early 1932. While in Paris, Miss Năm Phỉ was lauded by the French press as a “talented actress with captivating gestures” that could “rival even the best French singers and actresses.” 6 In a famous photograph on L’Illustration in August 1931, the Phước Cương troupe were shown getting their first taste of air travel at the open field at Vincennes [Fig. 2). Miss Năm Phỉ was photographed half-holding onto the plane door, half-dangling above the ground with a playful smile towards the camera, while her fellow performers line up in front of the plane in full performance garb, with a white pilot looking on from inside the plane.

Fig. 2: The first taste of air travel for

dancers from Cochinchina at the

Colonial Exposition. (Source:

L’Illustration, 22nd August 1931)

The native costume proved to be a popular look for the stars: in a congratulatory advertisement column, the tennis champion Nguyễn Văn Chim, one-half of the star tennis duo with Huỳnh Văn Giao, was also photographed wearing a traditional Vietnamese outfit and a traditional male turban, which he paired with a pair of leather shoes. 7 The Vietnamese press were elated, as it was the first time that native sportsmen were chosen to compete with their counterparts in France. The reading public hoped that these dashing young men, having won titles in Singapore and Colombo, Sri Lanka, would gain even more triumph and eventually proceed to the Wimbledon championship. 8 Sadly, the duo were defeated in the first round of the French Championships at Roland-Garros soon after their arrival in Paris. 9

Who wants to go see France?

Travelling to France to observe and participate in the Exposition spectacles was a recurring theme in the pages of the Vietnamese press, reflecting the rising socio-economic power and demands of the burgeoning Vietnamese middle and elite classes. In a fundraising event for Chim and Giao, their manager Triệu-văn-Yên invited Jacques Lê-văn-Đức, a seasoned bicultural traveller, to share his experience of travelling in France for interested inquirers. 10 Another savvy businessowner, Khánh Ký, owner of a photo studio in Saigon, also seized the occasion and bought recurring advertisements between March and April 1931 to offer tours with discounted transportation and accommodation for Vietnamese guests who would like to travel and enjoy the festivities. After the Exposition ended, the studio ran an attractive deal for customers who would like to have their photographs, presumably from the Paris voyage, printed on their beautiful paper stock imported on this special occasion. 11 The colonial government, in a more official tone, announced that it would provide guidance and support for members of the native mandarinate, elite and middle classes to travel to the Exposition; however, the government would not provide any financial assistance. 12 These accounts suggest that among the millions of attendees into the Exposition, a very small number might have been Indochinese elites.

On the one hand, the occasion became a tool for native Vietnamese elites to demonstrate their growing significance and engagement within Indochinese social, economic, and political life. In travelling to consume the extravaganza of the Exposition, they effectively identified themselves closer with the colonial gaze that regarded their compatriots, culture, and history through an Orientalising, othering lens. In the Exposition’s displays, young Vietnamese men and women were adorned in “traditional,” “native” costumes and situated near apparatuses of colonial modernity and adventure, creating an uncanny sight of cultural synthesis. It was an idealised image of a land with a rich cultural history and demure, beautiful, and mysterious subjects. These subjects, thanks to technological advancement and the success of the French mission civilisatrice, had now been packaged and delivered straight to the audience at Vincennes. In this idyllic mise-en-scène, the displayed people had been elevated from their position as lowly “silent native figurants” or performative extras. 13 They were transformed into the centre of attention at the Exposition, encapsulating the colonial order that the colonial government had been determined to project towards the French public. It stood in stark contrast to, and even helped to downplay and distract from, the bloody repression of the Yên Bái uprising at the hand of the colonial government in Indochina only a year prior.

Fig. 3: 21/5/31, Parade at the inauguration of the Annam pavilion at the Colonial Exposition. (Photograph by Agence Rol Photographic Agency. Source: National Library of France, Department of Prints and photography, EI-13 [1761], public domain.)

Rethinking Franco-Vietnamese collaboration

On the other hand, the Vietnamese experience of the Exposition reflected the ongoing demands of the native elite for more representation and agency in the “Pháp-Việt Đuề Huề” (“collaboration franco-annamite,” Franco-Vietnamese collaboration) era, which started under the reign of Albert Sarraut, twice Governor-General of Indochina (mandates: 1911-1913, 1917-1919). This era was intended to win over native support for the colonial regime with promises of liberal reform under French guidance. In this project of collaborative colonialism, Vietnamese-language press – written by predominantly male intellectuals educated in colonial schools and even returning from France, played a crucial role. While delivering news about the Exposition, members of the press also took on the responsibility of using this occasion to leverage for reforms in governance policies that would be more beneficial to the natives, if only to the elite and middle classes.

For instance, one opinion piece on December 19, 1931 addressed the issue of French politicians’ urge for political reform in Indochina, most particularly Vietnam, following the success of the Colonial Exposition. The article – published in Hà Thành ngọ báo – listed the chronology and characteristics of each colonial policy, from the decade-long “collaboration” policy to the “protectorate” policy that was expected to be picked up by Emperor Bảo Đại upon his ascension to the Vietnamese throne in 1932. Finally, it disagreed with the proposal for an “assimilationist” policy raised by veteran colonial military official, who hoped that the effectiveness of forced acculturation would be replicated in Indochina as it had in Africa. The piece wholeheartedly cited the words of Albert Sarraut himself regarding French rule in Indochina on the occasion of the Exposition: “… our protection method is not intended to frighten people, but a combination of characteristics between the white and yellow races. The day when the yellow race comes to recognise that France can really outdo everyone else on this globe and even ourselves, that is the day they will finally understand us, not as a teacher, since we do not want that, but understand us as guides, as familiar and intimate advisors and know that we can and are worthy of remaining in Indochina.” 14 The author of the piece was adamant that unlike “some tribes in Africa”, Vietnam had been a powerful nation with a deep literary culture and well-behaved people prior to the arrival of the French. Writing to represent himself as well as the Vietnamese elites, he reiterated that it was “the wish of the Vietnamese people” to receive material and spiritual enlightenment from the mission civilisatrice, and reminded the French and colonial governments to fulfil their promise of a just and benevolent rule for Indochina.

Colonial Nostalgia

In lieu of a definite, definitive conclusion, I would like to offer a more personal reflection on the mechanics of colonial nostalgia: at the time of writing, the National Archives Centre I in Hanoi is hosting an exhibition entitled “Đấu xảo – Nơi tinh hoa hội tụ” (Exposition – Where the cream of the crop converged) from January 25 to June 30, 2024. The exhibition features more than 300 archival items including official documentations, promotional posters, correspondences, and historical photographs from the National Library of France, Vietnam National Archives I, and private collections – many publicised for the first time. It chronicles the emergence of colonial expositions in colonial Vietnam following the French conquest: starting with the first expositions in Gia Định (modern-day Ho Chi Minh City, 1865) and Hanoi (1887), to the construction of Nhà đấu xảo (Grand Palais de l'Exposition) for the 1902 Hanoi Exhibition, til the last exposition in Hanoi in 1941. At the same time, the exhibition charts the participation and representations of Indochina, more specifically Vietnam, in international expositions in France – Paris (1878, 1889, 1900, 1925, 1931, 1937), Lyon (1894, 1914), and Marseilles (1906, 1922); in Europe (Brussels 1910); and in the United States (Chicago 1893, San Francisco 1904, New York 1939). Together, the combination of archives and exhibition panels tells the story of how the Vietnamese participation at the world’s fairs grew from a modest number within the French’s larger display of colonial conquests and victories, to gaining its own position and agency, becoming bigger in size, quantity, and increasingly more sophisticated in the quality of products and performances. These participations not only boasted to the world the advancements in commerce, industries, and constructions in Indochina, but also connected producers, investors, and consumers from France and overseas with the alluring Far East.

In press releases and news reports for the exhibition, we can observe how Vietnamese writers praise the brilliance of traditional Vietnamese arts and crafts displayed at these colonial expositions as evidence of how the Vietnamese had “brought our bells to play in faraway lands” and won over the hearts and minds of Western audiences with the products’ “exquisiteness, elegance, and uniqueness.” 15 A century apart, Vietnamese-language press discourses still share the same pride that the Vietnamese participation in colonial expositions in general and at the Paris Colonial Exposition 1931 in particular was a chance to showcase the fullest economic potentials and authentic cultural characteristics of Vietnam. It was also on the world’s stage where Franco-Vietnamese collaboration wasn’t a sheer promise but a palpable reality for the Vietnamese. And I, I have never been to Paris, and despite disagreeing with this mode of colonial nostalgia, I still share with my follow compatriots, then and now, a desire to go see Paris. To see and desire my naïve native self in a thousand exotic and quixotic mirrors of postcolonial yearning. To see what had been, what could have been, and what will never be.

LE Ha Thu Oanh, Alicia (she/they) is a Vietnamese writer, translator, and history researcher based in Hong Kong. She will be reading a Master of Philosophy in History at The University of Hong Kong in the Fall 2024. Email: alicia.oanhle@gmail.com