When watching films is resistance

In November 2018, Brigadier General Antonio Parlade Jr. of the Armed Forces of the Philippines accused university and school-based screenings of films about the Martial Law as being part of the ‘Red October plot’ to recruit for the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army (CPP-NPA). The accusation gave rise to statements of condemnation from hundreds of independent filmmakers, scholars, cultural workers and activists. These statements emphasised the danger that Parlade’s accusation poses to the freedom of expression guaranteed by the Philippine constitution.

The military’s linking of the memory of the Martial Law period to communism shows how the state cultivates “authoritarian nostalgia”1 in the Philippine public sphere. The spectre of the communist revolution is brought up to whitewash the atrocities of the earlier authoritarian order, and more disturbingly, to justify the return of dictatorial rule, this time under the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte.

My doctoral research project, which began in 2018, is about how the communist revolution is imagined in films and literary works produced in the decades that followed the toppling of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the 1986 EDSA People Power. Some of these works are films set in the Martial Law era. For many Filipinos who lived through this period, the memory of the dictatorship is intertwined with the memory of the revolutionary movement. Marcos invoked and magnified the threat of communism to justify the declaration of the Martial Law in 1972. The repressive conditions under authoritarian rule compelled a lot of Filipinos to join the revolution, which did not only embody the most radical form of anti-dictatorship resistance, but also offered a comprehensive agenda for the transformation of Philippine society.

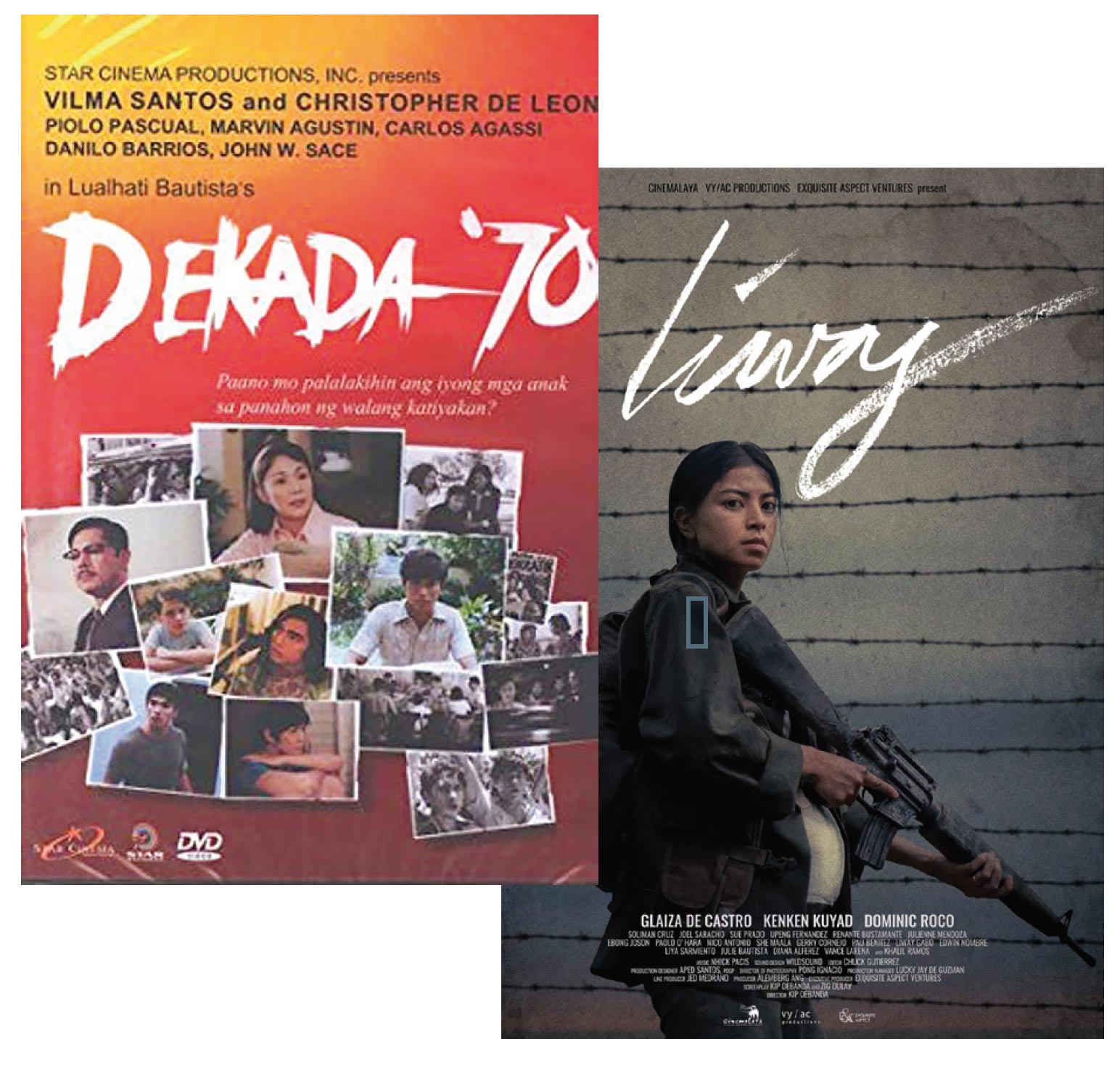

For Filipinos like me, born during the post-authoritarian period of democratisation and living through the present in which the revolution continues to rage on, Martial Law films are forms of “imagined memory”.2 They enable us to imagine and remember the experiences – of state violence, as well as of radical political involvement – during the Martial Law period. One prominent example is the commercially successful and critically acclaimed period melodrama Dekada ’70 (The 1970s, 2002). This film, produced by a major commercial film company, depicts the experiences of middle-class family in the titular milieu. In this film, the eldest son decides to join the communist armed movement, bringing to the fore the deep-seated contradictions that have long incubated in the family. At the centre of the film’s narrative is the political awakening of the mother, who not only begins to understand her son’s involvement, but also gradually liberates herself from the constraints of the social role she performs inside and outside the family home.

A visible commonality between Dekada ’70 and other recent films on the revolution is their examination of how gender and sexuality figure in an individual’s radicalisation. Such thematic concern relates to contemporary identity-based advocacies and social movement practices that prompt a nuancing, if not rethinking of, the class-oriented and nationalist politics associated primarily with the revolutionary movement. The independent films Barber’s Tales (2013) and Liway (2018) centre on women characters, whose expressions of empowerment are depicted as contingent upon, and linked to, their involvement in the communist movement. In other independent films like Muli (The Affair, 2010) and Lihis (Wayward, 2013), the experiences of gay members of the communist movement are highlighted, challenging the macho stereotypes associated with the popularised figure of the NPA guerrilla depicted in some post-EDSA action films. Apart from relating stories of courage shown by these revolutionary characters who have been cast as sexual minorities within and without the guerrilla zones, these films offer critical reflections on the communist movement’s own painful contradictions, as particularly evinced in their straightforward depiction of the persistence of heteronormative and patriarchal lifeways and values that revolutionaries need to wrestle from, and overcome.

The potency of these films lies in their capacity not only to memorialise the violence of the dictatorship, which continues to be the subject of systematic historical revisionism, but to also make use of the power of fiction cinema to examine the relevance and persistence of the revolutionary vision, especially in light of contemporary concerns such as identity politics. They produce fictionalised versions of the radical past that are significantly shaped by, while dialoguing with, the socio-political sensibilities of the present. And indeed it is the current nominally democratic order’s shared features with, and gradual transition to, authoritarian rule that urgently demand the surfacing of such radical memory practices.

Laurence Marvin S. Castillo, PhD candidate at the Asia Institute, University of Melbourne castillol@student.unimelb.edu.au