When motion blurs boundaries: made in Vienna, made in Japan

This paper discusses two textiles from the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection. What makes these two textiles fascinating is their link with Japan: one entitled “Japanland” by the Wiener Werkstätte artist Felice Rix Ueno (1893-1967) [fig.1]; the other, untitled and depicting bamboos, which had been attributed to the Wiener Werkstätte until 2015, when it was re-attributed to Japan [fig. 2].

The Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection includes nearly 4,000 textiles, some one hundred sample and pattern books, and dye chemistry texts. What makes this collection so unusual is that the small textiles represent cultures throughout the world and date from antiquity to the present. It thus offers an encyclopedic overview of textiles, allowing close examinations and comparisons. It was not collected by a team of experts in different areas, but was brought together through the eyes of Lloyd Cotsen (1929-2017). Cotsen was interested in lesser-known forms of art and had a passion for Asian cultures and Wiener Werkstätte objects. The collection reflects cultural diversity and exchanges, and a common human creativity. Assembled between 1997 and 2017, it was donated to the George Washington University in 2018 and is kept today in the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Center at The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in Washington D.C.

The Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection includes some distinct groups - among them the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops) textiles. The Wiener Werkstätte (1903-1932) were a cooperative of artisans established in Vienna in 1903 by the architect Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956) and the painter Koloman Moser (1868-1918). Founded on the principles of the Arts and Crafts Movement, it is considered a key organisation in the development of modernism, anticipating the Bauhaus. With financial support from the textile industrialist Fritz Wärndorfer (1868-1939), the Workshops were expanded with a textile department (1909) and a fashion department (1911). The Wiener Werkstätte produced textiles characterised by bold patterns, designed by artists and students of the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts), where Hoffmann and Moser also taught.

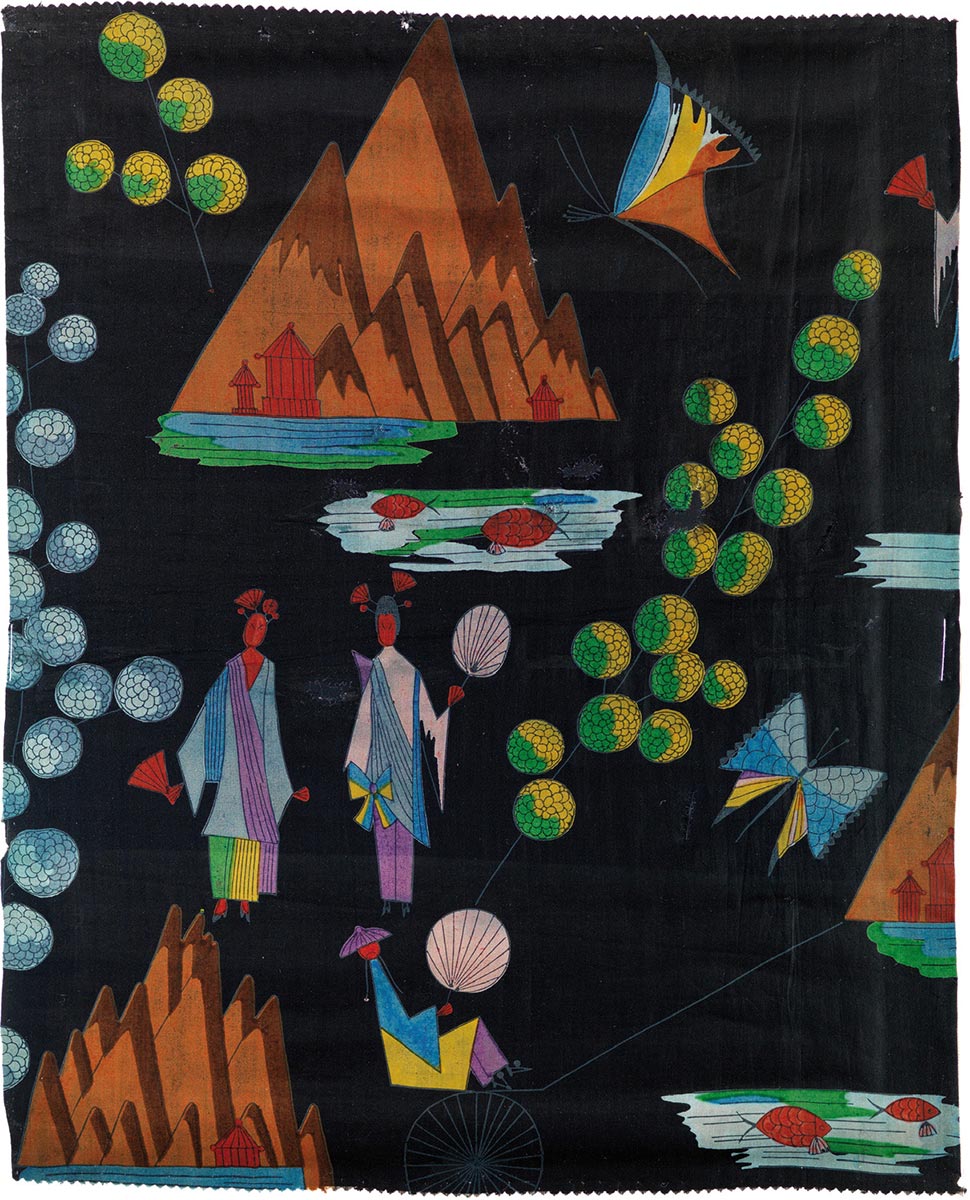

Fig. 1: Felice Rix-Ueno (1893-1967), Japanland, Vienna, 1923, silk, printed, 38 x 42 cm. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-1859, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum.

The Wiener Werkstätte Textile Collection in Washington represents one of the most significant ensembles in a patrimonial institution outside Vienna. It includes more than 350 items, representing some fifty designers, and ranging from the 1910s to 1930, giving thus a good overview of the textile production by the Wiener Werkstätte from the beginning to the end. In this group, two textiles are especially intriguing because of their relation to Japan, and because they offer captivating examples of cross-cultural transfers.

The influence of Japanese art and design in Europe during the second half of the 19th century – after the reopening of trade of Japan in 1858 – is well known and generally called “Japonisme.” What still needs to be more explored is how much European and Japanese cultures affected each other, especially at the time when Japanese men and women were coming to Europe and Europeans were going to Japan to study and teach, blurring the boundaries between these two cultures.

Moser and Hoffmann cited the significant influence of Japanese craft in their 1905 work-programme for the Wiener Werkstätte. While teaching at the Kunstgewerbeschule, both applied Japanese principles and exposed their students to various didactic resources, among which the technique of katazome, a Japanese dying method that uses a resist paste applied through stencils called katagami. This technique resulted in precise pattern designs, including that of bamboo (fig. 3). The Museum für angewandte Kunst (MAK or Museum of Applied Arts), with which the Kunstgewerbeschule was closely associated holds a large collection of katagami stencils (~8,000). It was donated in 1907 by Heinrich Siebold (1852-1908), a German antiquary, collector, and translator in the service of the Austrian Embassy in Tokyo, to the Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie (Austrian Museum of Art and Industry), today the MAK.

The students and artists connected with the Wiener Werkstätte used these stencils and also created their own. This technique, even though less frequently used and less complex than the block printing technique, was in this way part of the production process of some of the Wiener Werkstätte textiles and reflects the impact of Japan. Unfortunately, due to their fragility, none of the stencils produced by the Wiener Werkstätte have survived, as far as we know, unlike the wooden blocks.

The fact that one of the Wiener Werkstätte textile designs is entitled “Japanland” and that bamboos were part of their repertoire does not come as a surprise. Nor does the use of stencils. But what makes these two textiles so interesting is that the first one was made by Felice Rix Ueno and reflects the exploration of Japanese culture in Europe, while the second textile, depicting bamboos, is such a blend of two cultures that its origin is uncertain.

Felice Rix-Ueno, also called Lizzie, was born in Vienna on 1 June 1893. She was the eldest daughter of Julius Rix (1858-1927), a rich entrepreneur and temporary director of the Wiener Werkstätte, and Valérie Rix, née Löwy (1875-?). Between 1912 and 1917, she studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna and attended classes taught by Josef Hoffmann. On 21 October 1925, she married the Japanese architect Isaburo Ueno (1892-1972), who had graduated from Wasada University in 1922 and was hired at Hoffmann’s architecture firm in Vienna. After their wedding, the couple moved to Japan, where Felice Rix-Ueno continued to create designs for the Wiener Werkstätte until 1930. Her marriage to Isaburo and move to Japan led her to lecture at the Kyoto City University of Arts, from which she resigned in 1963 to create, with her husband, their own private school, the Kyoto Interactive School of Art, expanding concepts she developed with the Wiener Werkstätte, and setting up teaching methods that were inspired by the Bauhaus, with an emphasis on individual imagination.

While working for the Wiener Werkstätte, she designed in several fields (illustrations, book covers, enamel works, etc.). Her major strength was in textile patterns, with a production of some 112 designs. Out of these, 69 were designed while she was in Vienna and date from 1913/17 to 1925, while the 43 remaining were created after she moved to Kyoto and date between 1926 and 1930.

We do not know if Felice Rix-Ueno visited Japan before her wedding, but what is certain is that her design entitled “Japanland” dates back to 1923, prior to her move to Japan, and depicts several Japonisme motifs: jagged mountains and pagodas, butterflies, stalks of flowers, fish in ponds, kimono-clad women with fans, and a man with a large fan seated in a rickshaw (jinrikisha). They are block printed in shades of brown, red, orange, green, blue, yellow, pink, and purple, on a black ground. The motifs follow the contemporary fashion and present a naive simplicity characteristic of her Vienna period, influenced by a taste for exoticism. The rich palette indicates a complex production, as each colour corresponds to a different block – a technique most often used, despite its complexity, for Wiener Werkstätte textiles. Her Kyoto period sees the development of more abstract motifs, with delicate lines and colours, testimony of a fusion of artistic traditions in Vienna and Kyoto.

Fig. 2: Wiener Werkstätte or Japanese sample, Vienna/Japan?, early 20th century, silk, satin weave, stenciled or printed, 17.5 x 15 cm. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0193.270, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum.

The second textile, depicting bamboos [fig.2], was acquired by Mr. Cotsen in 1998, on the art market in Munich along with textile samples from the Wiener Werkstätte. It was attributed to this cooperative until 2015. Although it is close to the design called “Bergfalter” by Koloman Moser (fig. 4), it is no longer recognised as a Wiener Werkstätte pattern. Its similarities with Japanese katagami suggest that it could have been produced in Japan. The question remains open, and it testifies to how much the transfer and assimilation of cultures could result in a fusion, rendering the attribution of a textile sometimes very difficult.

Further research would allow for a better evaluation of the cross-cultural exchanges between Japan and Europe in the early 20th century. What these two textiles reveal is that, while the first textile clearly belongs to European Japonisme, the other one blurs the boundaries and suggests an assimilation and a fusion of two cultures, opening the door to new questions and investigations, not only on the transfer of motifs and techniques, but also on the impact of education through generations and cultures. How did the use of foreign resources, such as katagami stencils, influence motifs and techniques in European art? How did artists like Felice Rix-Ueno and her husband, through their education, art, and teaching, contribute to the transmission of knowledge at Hoffmann’s studio and the development of Japanese modern art? These two textiles from the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection leave us with the potential to discover new stories, testifying to exchanges, transfers, assimilation, and fusion between two different cultures.

Marie-Eve Celio-Scheurer is the academic coordinator at The George Washington University Museum and at The Textile Museum in Washington D.C. for the new Cotsen Textile Traces Study Center. Dr. Celio develops scholarly programming, builds academic collaborations, and facilitates research related to the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection. mecelio@gwu.edu, meve.celio@gmail.com