Visions of the 1930s: Jack Ephgrave's Shanghai

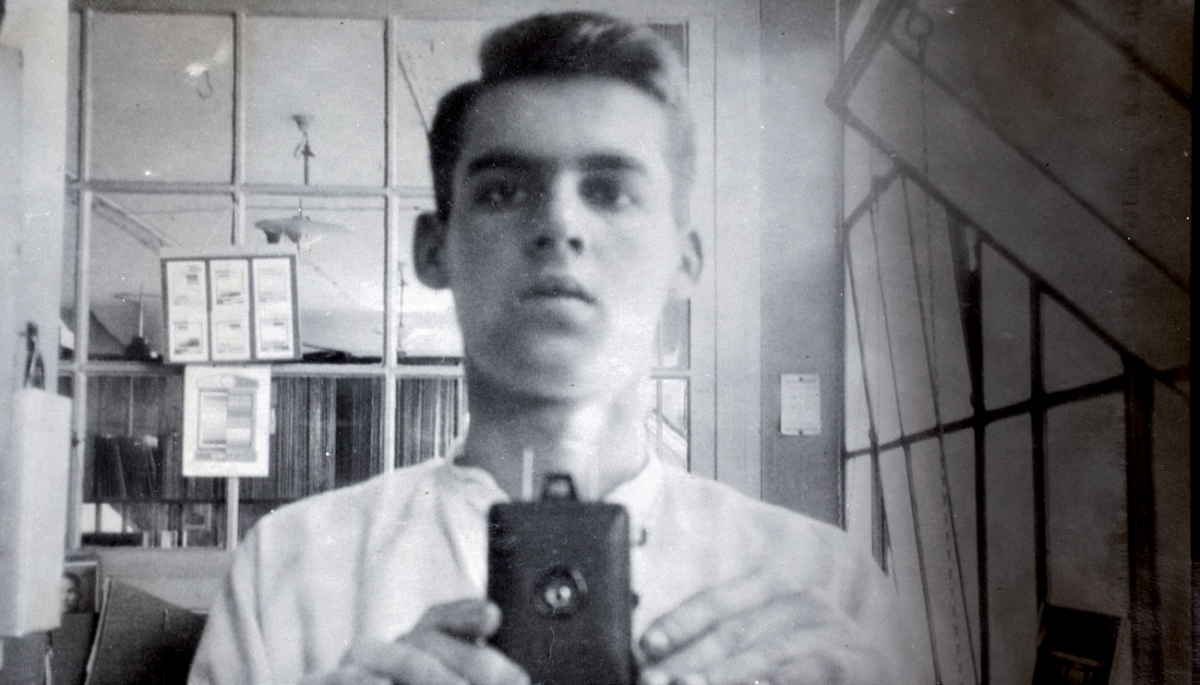

In about 1929, shortly after he began working for the first time, a young man in Shanghai seems to have used his new-earned wealth to buy a camera. With all the fearlessness and curiosity of a neophyte and, it turned out with some natural talent and technical skill, Jack Ephgrave then set about over the next five years documenting the city in which he lived, his workplace, and his family. And then, for over 70 years, the photographs lay carefully preserved but unseen outside his family.

John William Ephgrave (1914-79), always known as Jack, was born in Shanghai in October 1914. His father had arrived in the city in 1912 to work for a department store, and would in time become one of its directors. Jack started off as an apprentice in the printing department of British American Tobacco’s China operation (BAT), the British Cigarette Company (BCC), and later worked for its subsidiary Capital Lithographers Ltd. In later life he rose to hold a senior position in the company’s global headquarters in London before retirement in 1972.

BAT, as well as being the single biggest tax-payer in republican China, had a profound impact through its marketing and publicity operations on China’s modern visual culture. Its advertising hoardings, cigarette packet cards, and calendar posters, were designed by some of China’s most influential graphic artists, and Ephgrave by 1941 was head of the Artists’ Department at Capital Lithographers. But it is young Jack’s experiments with photography that are, for me, the striking thing about his China career.

The two albums that emerged contain 1,000 photographs. There is some able street photography, there are experiments with self-portraits and juxtapositions, snaps of family members, and of the armoured cars of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps (which Jack had joined). There are many grim shots of the blasted ruins of the city’s northern Zhabei district in the aftermath of the ghastly February 1932 Sino-Japanese battle in Shanghai. There are failures amongst the successes, and the mundane and repetitive that marks any unedited raw collection. Ephgrave’s life encompassed the insular world of Shanghai’s settler community, but they are no less striking in the vignettes they offer of 1930s China’s most self-confident and vibrant city. There is even a snapshot of a snowman in the public gardens at the northern end of the Shanghai Bund.

The camera had arrived in China with the British war fleet that sailed on Nanjing in 1842 during the first Opium War. While the daguerreotypes that we know were taken on the banks of the Yangzi River in July 1842 appear not to have survived, the legacy of the photographic enterprise that developed over the course of the next one hundred years in China’s treaty ports is extensive. Much of the archive of that century of photography can be found in public archives and libraries internationally. Superb collections can be found in the Getty Research Institute, British Library, Wellcome Library and the Hong Kong Museum of History (which in 2013 acquired on permanent loan what is now known as the Moonchu Collection of Early Chinese Photography, originally developed by Terry Bennett).

Jules Itier, Felix Beato, John Thompson, Lai Afong and other canonical figures are well represented in such collections, but vernacular photography is less readily accessible. Since 2006, the University of Bristol’s Historical Photographs of China (HPC) project has been locating, digitizing and placing online some of the hidden archive photography held by families with historic links to China’s port cities (www.hpcbristol.net). These are families whose ancestors lived in or visited China, and who commissioned, bought, or like Jack Ephgrave took themselves (and sometimes stole) the photographs that survive as prints in albums, negatives and slides. The project has been presented in the Newsletter before (issue 76, Spring 2017), but as it continues to grow, new collections are offered by members of the public from across the world, and it has embedded within its cross-searchable holdings other publicly-accessible digital archives (most recently 4,700 photographs by Hedda Morrison from Harvard-Yenching Library; www.hpcbristol.net/collections/morrison-hedda).

The latest large set of images, digitized by the project team and unveiled online, contains an extensive set of photographs documenting revolutionary events in Wuhan in 1911 (www.hpcbristol.net/collections/wyatt-smith-stanley), while the most recent collection to arrive in the office covers two years in the (off-duty) life of a British intelligence officer in early Communist Shanghai. The geography of the foreign presence in China certainly shapes the collection, as it also shaped the bodies of work produced by the famous. Chinese Maritime Customs staff, consuls, businessmen and missionaries largely moved on what became familiar circuits of postings from port to port. They also spent vacations in the same resorts, or went on sightseeing trips to the same temples or natural sights. But while there is always something predictable in any set that arrives in the office in Bristol, there is always something new, unusual and exciting, like the fruits of Jack Ephgrave’s first flush of love for the camera.

Robert Bickers is Professor of History at the University of Bristol and HPC Project Director (Robert.Bickers@bristol.ac.uk). The HPC’s Jack Ephgrave collection can be found at www.hpcbristol.net/collections/ephgrave-jack.