Transoceanic Africa-Asia connections

<p>Reviewed titles:</p><p>Ali, O.H. 2016. <em>Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery Across the Indian Ocean</em>. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.</p><p>Burton, A. 2016. <em>Africa in the Indian Imagination: Race and the Politics of Postcolonial Citation</em>. Durham and London: Duke University Press. </p><p>Sellström, T. 2015. <em>Africa in the Indian Ocean: Islands in Ebb and Flow</em>. Leiden and Boston: Brill.</p>

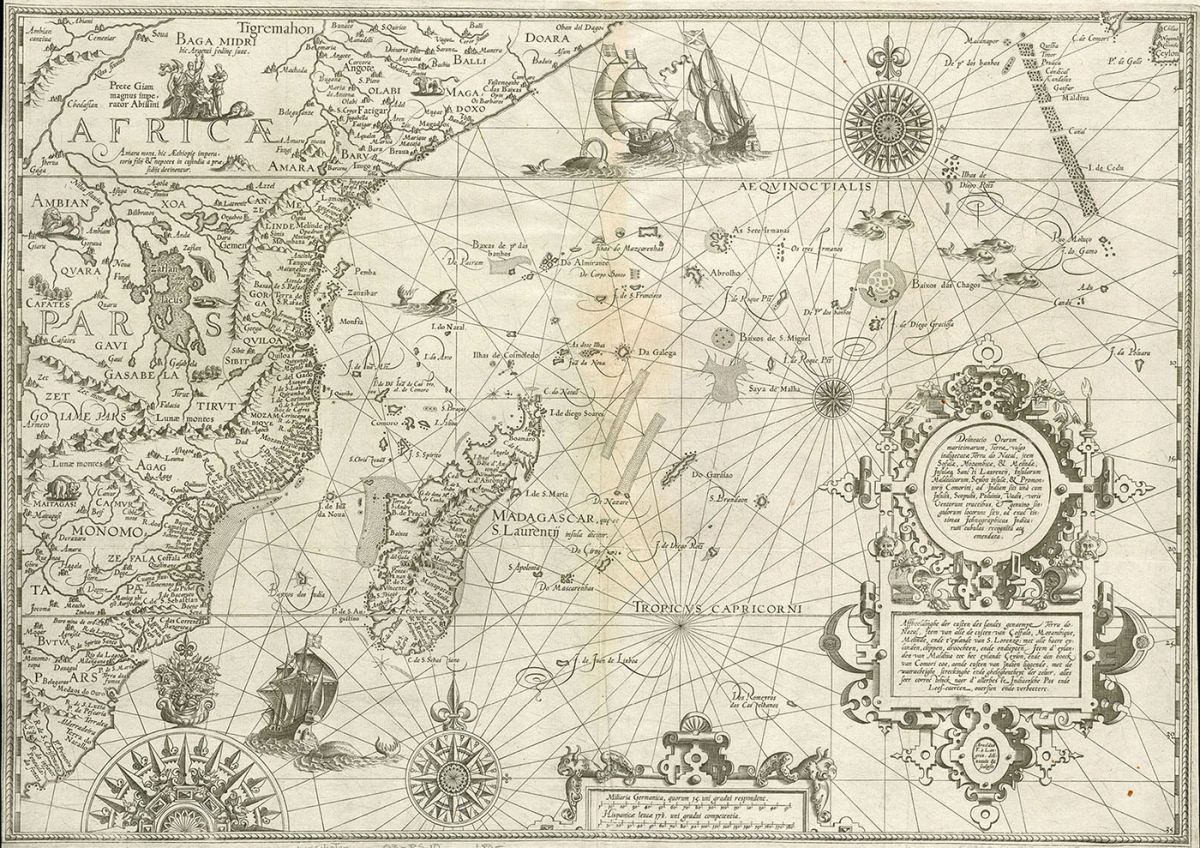

The Indian Ocean was not always the ‘Indian’ Ocean. It has also been an African Ocean known as the Zanj Ocean, Abyssinian Ocean, and Ethiopian Ocean. These names forgotten in popular imaginations as well as in academic scholarship represent a larger problem surrounding the maritime littoral: the neglected historical and contemporary role of Africans in this seascape and on its shores. Yet, in the last decade new studies have been appearing in the field, and the three books under present review represent this new trend.

The ocean has historically been a highway for large scale and long term flows of communities, commodities, and ideas, in which millions of people willingly or unwillingly travelled, traded, coerced, and commodified. Africa’s major collaborators have been the Asian communities before and after the European and American colonial/imperial endeavours. Both Asia and Africa, the two major continents sharing the ocean’s shores, have historically plotted their socio-political, economic, and religious trajectories under the direct influence of the ocean. This review essay is mainly concerned with this aspect: how did the Indian Ocean play, and how does it continue to play, a crucial role in the memories of and studies on the Afro–Asian interactions in the past and the present.

The oceanic scape in Africa–Asia Studies

In the past decade, there have been increasing attempts to identify these interactions between Asia and Africa, inside and outside the region. The major conferences organised by the University of Goethe in Kuala Lumpur (2014), Cape Town (2015) and Frankfurt (2016) and by the International Institute for Asian Studies in Accra (2015) and Dar es Salam (2018) are worth noting in this regard. The latter’s first conference with participants from 40 countries in 55 panels resulted in the formation of a consortium called the Association for Asian Studies in Africa, headquartered in Accra, and has identified and energised ‘Africa–Asia’ as a new field of study. Relatedly, there have been remarkable academic initiatives by Chinese, American, Indian, South African, Malaysian, Singaporean, and European institutions, not to mention the international diplomatic conventions for South–South collaborations between postcolonial Asian and African countries, starting with the Asia–Africa Conference in Bandung in 1955 and stretching to its 60th anniversary conference re-hosted by Indonesia in 2015. All these efforts have produced a significant amount of academic projects to record, analyse, and advance the nuances of these linkages, yet the lion’s share is focused on the interests of China in Africa, mainly emphasising political and economic negotiations and investments, but also social, cultural and demographic implications. Given the recent ‘reappearance’ of China after almost 600 years, this sudden boom in literature and discourse has created an imbalanced academic orientation towards the deep genealogies of transcontinental exchanges and encounters between the two regions. The Indian Ocean often appears only marginally as a memory scape of the historical past to be invoked when the situation demands it.

Notwithstanding, the wider Asia–Africa discourse, several edited volumes, and conference proceedings, have recognised the role of the ocean in the transcontinental interactions. Two book series, for example, (published by Ohio University Press, edited by Richard B. Allen; by Palgrave MacMillan, edited by Gwyn Campbell) have published volumes with an emphasis on African interactions with Asia through this littoral. Within this field, one booming zone of study is slavery in the Indian Ocean. The subfield explores nuances of otherwise unrecognised forced relocations of Africans and Asians, from within different Asian-African regions to such faraway places as Australia. 1 Some other common themes, such as piracy, have also found significant scholarly attention, particularly after the increase of Somali piracy in and around the 2010s. Several other individual researches have explored the African involvement in the oceanic mobilities through intellectual, religious, and legal networks. The works on Islamic legal and political encounters in the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries have presented fascinating African cases in the wake of European colonial expansions. And, of course, the histories of European and Arab colonialisms in East and South African terrains through enslavements, forced migrations, genocides, armaments, organised plunders, along with negligible tints of infrastructural developments, have been subjects of serious studies through the frameworks of the oceanic scape.

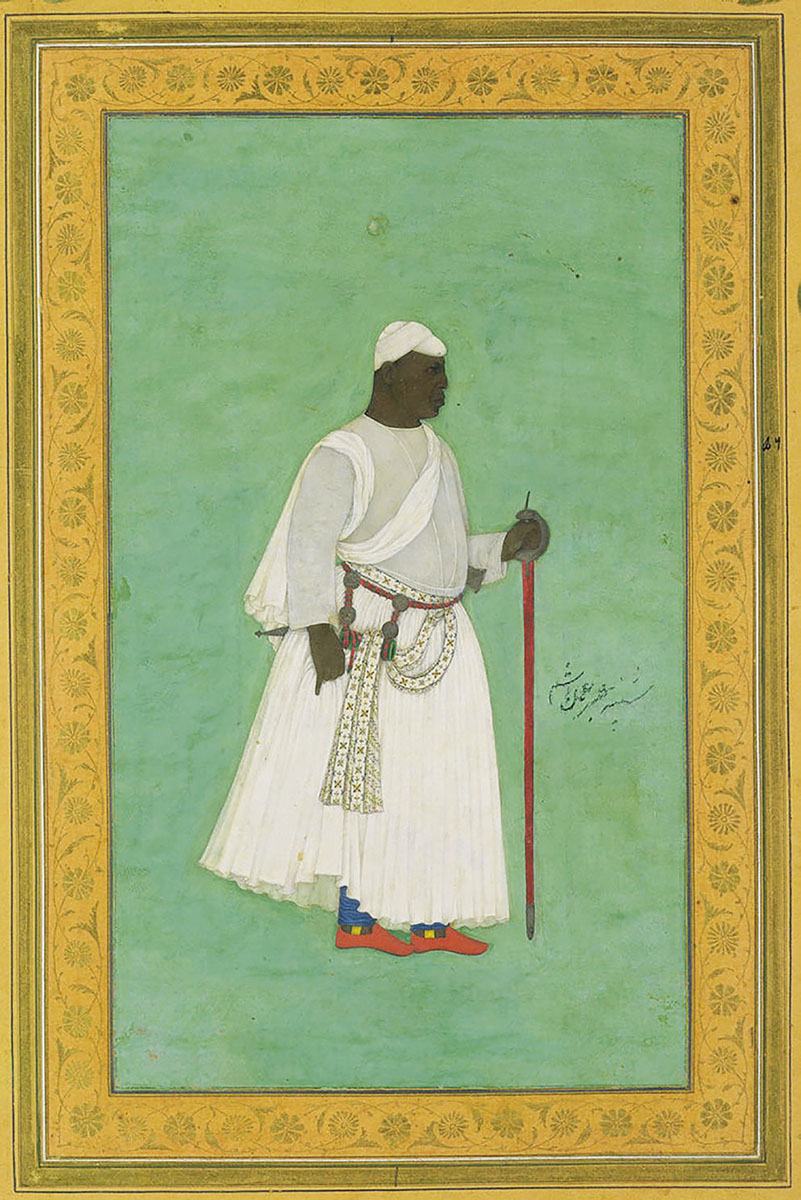

The three books under review slightly move away from these trends in present historiography, yet they are informed by and have emerged from the wider currents in the African and Asian connections and conflicts because and despite of the European colonial expansions. Omar H. Ali follows the life of Malik Ambar, an iconic figure in the transoceanic and transcontinental mobility of the 16th and 17th centuries, who dramatically went from being a teenage slave to a statesman and kingmaker; Antoinette Burton focuses on gradations of race, gender and politics in the literature produced on the Africa–India entanglements in the 20th century; and Tor Sellström foregrounds the African islands in the littoral as products and producers of the maritime sociocultural geography. These works together represent three major aspects of East and South Africa’s predicaments with the maritime world: that of slavery and forced migrations, the depictions of Africans as an inferior racial category within the Indian (Ocean) literary contexts, and the islands as marginalised terrains in geopolitical concerns of mainland countries, be they in Africa or elsewhere.

Phenomenal life of an African slave

Omar Ali’s study tells of the ways in which Africans were forced to leave their homelands as slaves and travel thousands of miles. 2 Malik Ambar was such a slave, yet a figure who resisted the Mughal expansion into the Deccan through his diplomatic skills and military tactics (bargi-giri). For several decades in the late 16th and early 17th century Ambar was the sole barrier for the Mughals to the Deccan. Born into and raised by an Oromo tribe in the Ethiopian highlands, enslaved and exchanged in the slave markets of Africa and the Middle East before ending up in South Asia, Ambar travelled a long way in his life, similar to many other thousands of Africans before and after him. In India, Malik Ambar was first sold in the Sultanate of Ahmednagar to the chief minister Mirak Dabir aka Chengiz Khan, who himself was once a Habshi slave and had risen to his position in the royal court. Under his tutelage, he learnt “the ways of the court and state operations”(p.42). Following the assassination of his master in a royal plot, Ambar travelled between different kingdoms in the Deccan region working for several commanders and rulers. Over the course of time, he “increased his following across the western Deccan” by inheriting the army of his former commanders and harassing Mughal forces and capturing their supply convoys. Utilising this manpower, military and diplomatic skills, and marriage alliances, he rose to prime minister of the Ahmednagar Sultanate where he controlled the enthronement and dethronement of sultans, built up marvellous cities and forts, and excelled in administration of law and order.

In between all the ups and downs of his life, Ali argues that Ambar depended on the life principle of namak halal or ‘true to the salt’—a concept and tradition of being loyal to the master—in his services to the Nizam Shah rulers, no matter who sat on the throne. However, although true that he was loyal to the sultanate during several hardships, he also poisoned a ruler to death when things did not go as he had planned; or more precisely, when the then Persian queen called his daughter “a mere slave girl”, “concubine” and a “kaffir” (p.65). Ambar poisoned both the queen and the king and replaced him with a five-year-old boy as the new sultan. Ambar served his interests more than that of the master(s) and the throne.

Ambar’s story has attracted the attention of several scholars in the last century, but Ali ‘oceanises’ the story through comparative and connected histories. He provides a vivid comparative description of Ethiopia, Iraq and India as backdrops for Ambar’s trails. Ambar’s later life has been well recorded, but the author accommodates a ‘discursive strategy’ of contextualisation and imagination to fill the gaps in his early life for which “documentary evidence is sparse” (p.135). Through this mechanism of interpretative connected historical reading, we get a detailed image of the lives and oceanic journeys of not just Ambar, but of also several other African slaves from East and Central African regions. 3

Asia sites/cites Africa

By the mid-nineteenth century, the flow of slaves between the continents was reversed; now instead of slaves from African lands, the bounded and free labourers from South Asia and beyond filled the ships as a pivotal workforce for European plantations, colonial bureaucracies, and infrastructure developments in Africa. In the colonial period up until the late 20th century, this process created a layered racial hierarchy in Africa as much as in the Indian soils and minds. Despite claims for Afro–Asian solidarities or because of the Afro–Asian (unequal) collaborations post-Bandung Conference (1955), the ‘brown’ often asserted itself as an in-between or better racial category vis-à-vis the ‘black’. Those of Indian origin distanced themselves from black identities in their social, political and cultural struggles and sought allegiance with the privileges of the white. The (re)presentation of these racial regimes in the postcolonial writings of Indian/African authors form the central emphasis of Antoinette Burton’s book, Africa in the Indian Imagination.

Burton takes the literature as emblematic of the Africa–Asia interactions and the ways in which those are narrated, negotiated, cited and sited. With a focus on writers with an Indian background and their citationary practices, Burton elaborates on the politics (and biases) of the connections and their tellings, in which Africa, Africans, and ‘blackness’ are circulated as a recurrent trope in the Indian imaginations. These postcolonial racialised image-nations emerge from the hierarchised privileges that the Indians in Africa enjoyed or strived for during the colonial and apartheid regimes. 4 Before he would become ‘Mahatma’, Gandhi’s political, social, and communalist predispositions against Africans in early 20th century (explicated through his pejorative uses of such terms as ‘kaffir’), thereby distancing himself from black people, was part of a larger Indian aspiration of placing themselves above the Africans, according to which they would in 1919 request the League of Nations “to reserve Tanganyika an ‘Indian’ territory for the purpose of Indian colonisation” and which led Sarojini Naidoo to support this Indian colonial ambition by saying that “East Africa … is the legitimate Colony of the surplus of the great Indian nation”(p.10). Burton analyses the nuances of such south-south racial and sexual politics by historicising “the role of Africa and of blackness in the emergence of a postcolonial Indian identity that was both transnational and diasporic, but no less conscious of or invested in racial and sexual difference for being both” (p.14).

The multi-sited and many-cited real or fictional journeys of protagonists between India and Africa as well as within Africa deepen our understanding of the modes through which racialised citationary practices plugged into the postcolonial narratives. Burton takes two novels, one travel account, and (auto-) biographical writings to caricature how often those writers walked the thin line of racism and crossed over to the racialist, if not racist, terrains in their writings. This literary corpus stands as a rich archival repository for historical enquiries into the racial and sexual sentimentalities of the authors and their wider contexts. In this archive of mind-sets, we not only see how often skin colour and race conflicted with and compromised each other, but also we witness testimonials of gender collaborations that form interracial solidarities, whether in a patriarchal misogynist setting among brown and black men, or feminist/female understandings of motherhood or sisterhood between and among black and brown women.

Looking through the works of four authors of South Asian descent (Anasuya R. Singh, Frank Moraes, Chanakya Sen, and Phyllis Naidoo), Burton investigates how Africa and Africans have been cited and sited as secondary and tertiary categories in which race, class, sexuality, legality, technology, and politics deepened boundaries and frictions in the envisioned Afro–Asian solidarities of the postcolonial world. Out of the four, only Phyllis Naidoo asserts a non-racial history of Africans and Indians in the anti-apartheid struggles, while the remaining authors follow a racialist citationary apparatus to describe and enliven African protagonists, plots and places. Beyond these convolutions, gendered and sexualised solidarities emerge across the racial boundaries. While the political mentoring by an African companion (Serete) for Indian brothers (Srenika and Krishandutt) in Singh’s novel “confirms the possibility of cross-racial brotherhood”(p.45), Srenika’s wife Yagesvari and the family maidservant (Anna) are unable to converse with each other (and thus stands as a critique of universal sisterhood), the same way Indian women would be scapegoated for failed Afro–Asian collaborations in Sen’s novel, in which the cross-racial “collaborative patriarchy” is in the driving seat and “Afro-Asian solidarity is a homosocial experience at the expense of a brown woman”(p.105). These lowered and stooged profiles of women in the transcontinental exchanges are reversed once we come to Naidoo’s (auto-)biographical writings in which, at least in one instance of the activist Cynthia Phakathi, gender solidarity “interrupt[s] cross-racial alliances and empower[s] an African woman not just to prove her worth or get her job back but to tell her African male employer” the status of her work (p.141).

These writers represented the larger Indian and African connections of their times and they fed into the existing political and diplomatic agendas, whether it was Cold War or Africanisation. Such issues are reflected in the citational practices of respective authors. Burton convincingly tells us how the authors in the twentieth-century postcolonial Indian and African intellectual realms imagined themselves as harbingers of new forms of change and created an assertion of racial bias through more advanced forms of technological, educational, and cultural exchanges.

African islands of the ocean

The same predicaments of memory on the oceanic melanges of the past is very much part and parcel of the present on the African islands in which the intermixed communities of Asian, African, and European origins create a maritime demography with increasing concerns over their coexistences in the contemporary island nations. These islands are the focus of Tor Sellström’s Africa in the Indian Ocean. If the Afro–Asian interactions in Ali’s and Burton’s works had spatial and temporal segregations through inconsequential/discontinued contacts of a dislocated Ethiopian slave or a Goan traveller, or as a writer who fictionalises the events and moments of temporary contacts (if not in the South African context of Naidoo), the islands in the ocean do live with the remnant bulks of Afro-Asian intermixtures with deep histories across centuries. Those aspects define present socio-economic, religious and political realms of the island nations in different ways, be it in Madagascar, Comoros or any other islands in the area. Sellström presents a quick trip through all these aspects in his book.

Apart from bringing these islands to the forefront of discussions by locating them in the land-based African and sea-based international maritime geopolitics and describing their predicaments in social, economic, political, and environmental (trans-)formations, Sellström’s book as such does not have an overall argument or narrative. He himself admits this: “The book is not the outcome of original research, nor does it claim to break new theoretical ground” (p.xii). This lack of any persuasive arguments in the historical or contemporary situations might make the book less attractive a read, and might appear like a long Wikipedia entry, but it should be useful for general readers to get an overall idea of these islands.

The islands under discussion are Madagascar, Comoros, Reunion, Mauritius, Seychelles, Mayotte, and Chagos. In the long Introduction (‘From Zanj to Maersk’) Sellström describes their common features, histories, politics, and problems. In the following chapters, he enquires similar themes with regard to each island country, such as the geographical and demographic specificities, colonial and postcolonial economic and political transitions, diplomatic and international engagements. For the purpose of this essay’s focus, what becomes clear in his description of these islands is the ways in which the oceanic mobilities in precolonial and colonial periods dramatically influenced the demographics, cultures and politics of these islands. Just like the movement of slaves, labourers, pirates, and traders shaped their recent past, the large scale migrations in the premodern periods, such as that of the Austronesian, Bantu, Arab, Swahili, and other communities, have also defined the very nature of each island’s historical and contemporary situations. The interactions between these Asian and African communities along with the European colonialism provide irrefutable spectacles of transoceanic interactions which produced creole/hybrid, multi-racial/ethnic communities. Some of the islands had also been drastically transformed through Western colonialism, be it the ancient island countries such as the Comoros or other later-populated islands such as Reunion and Mauritius, and the same colonialism continues to shape the fate of some islands like Chagos and Mayotte where the UK, USA, and France continue to breach international laws and transform these places into “the scenes of human tragedies” (p.306).

Concluding remarks

Taken together, the works of Ali, Burton and Sellström present a conglomerate of historical and contemporary interactions of Africa with the oceanic littoral. While the narratives on slave mobilities and the representations of Africans in postcolonial Indian writings demonstrate a transoceanic entanglement with Asia at large, or India in particular, the socio-political and economic (trans-)formations of African islands in the ocean illuminate the prosperous past of Africa–Asia exchanges along with their contentious present in nationalistic and majoritarian political rhetoric. The oceanic world and its impacts on the lives of African individuals, nations and institutions are irrefutable both in the past and in the present despite the politicised, insensitive and ignorant attempts to erase or ignore the vivid trajectories. Future research and initiatives will enlighten us more on the various faces and phases of Africa’s role in the littoral and of Africa–Asian connections across the ocean.

Mahmood Kooria, Leiden University (m.kooriadathodi@hum.leidenuniv.nl).