The tipping point for alternatives in East Asian arts

“Would this be the time for a permanent social change?” and “Could alternative artistic and creative practices facilitate the transformation?”, are two questions posed by the spray painted image of a masked protestor pitching a translated copy of Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point in Yaumatei, Hong Kong (see fig. 1 below).1 Created by a local graffiti artist during the ‘Fishball Revolution’ in February 2016, this larger-than-life stencil adapts and builds upon the original visual message made by British street artist Banksy in Bethlehem in 2005.2 In Banksy’s work, commonly known as the Flower Thrower, a protestor is armed with a bouquet of colorful flowers to promote peace, instead of grenades, rocks or Molotov cocktails to be thrown at adversaries.3 However, in Hong Kong’s version, the Book Thrower, the protestor is equipped with the knowledge that a sudden but profound transformation of paradigms, policies and practices is possible when, as Gladwell suggests, “the moment of critical mass”, is reached.

Echoing the queries put forward by the stenciled protestor, this special issue examines the artistic and creative practices emerging in East Asia and how they are gaining prominent status, not only in the art scene, but in society as a whole. Rather than mirroring social transformations, these groundbreaking practices initiate thought-provoking alternatives for both art and life. They have become instrumental for bringing forward new subjectivities and reshaping the intrinsic values of social and cultural well-being.

“Art needs to be more than a cosmetic intervention, if it is to be a catalyst for cities conducive to well-being.”4

As with the majority of alternative artistic and creative practices, the significance of Book Thrower is interdependent with the temporal, spatial and socio-political dimensions of the creation. Hong Kong’s unlicensed hawkers once were actively present on the city’s streets during Chinese New Year celebrations, whereby the authorities would close their eyes to these unofficial business activities; that was, until regulations were tightened in 2014. Despite local groups demanding tolerance for the hawkers’ rights during the past years, the conflict between different stakeholders escalated in early February 2016. In the evening of 8 February, supporters gathered to defend the hawkers, which led to violent clashes between police and a few hundred protestors. What was at stake was not only the local food culture, but the more profound questions of the overall viability of local culture and the geopolitical status of Hong Kong, which since the civil unrest known best as the Umbrella Movement in autumn 2014, has been a much debated issue, especially between the ‘localists’ and pro-Beijing groups. Nearby, while the rioters’ fires were still burning, a local graffiti artist created his visual statement to aid the cause. The value of his work was not limited to immediate support; it has not been painted over, and now provides a discursive, and even, commemorative site. The desire to reconsider the city’s future was later proclaimed by an unknown person who engaged in visual dialogue with the Book Thrower by adding a four-character slogan, “Freedom originates in the mind”, at the tip of the protestor’s pointing left hand.

Besides demonstrating how alternative artistic and creative practices are timely responses to socio-political issues, the Book Thrower illuminates four interrelated themes shared by the authors in this special issue ‒ the ground-breaking forms of sites, collaborations, agencies and aesthetics emerging in East Asia; their significance in questioning the current value and power structures in society; building up a sense of belonging; and fostering new subjectivities. Through transdisciplinary research, combining methods and theories from art history, media studies and urban studies, as well as benefitting from close analysis of versatile case studies, the aim is not only to elucidate how alternative artistic and creative practices in East Asia are taking an ever more crucial role both in art and social transformation, but also, to exemplify the tangible and intangible contingencies, challenges and opportunities these practices are facing today.

Amplified alternatives for local needs

Since the 1960s, diversified forms of art activism have reshaped relations between arts and politics around East Asia with varying intensity and results.5 Increasingly prominent transformations in economics, geopolitics and the global art scene in the 1990s, further emphasized the active role of contemporary art in the broad area of social justice and change. At the same time, the pre-existing cultural hegemonies and the dominating Euro-American paradigm in arts were challenged, resulting with the “rejection of a hierarchical internationalism in art”, which is one of the main features of Asian contemporary arts today.6 As the articles in this special issue illustrate, even if the new forms of alternative artistic and creative practices, at first glance, might seem to mirror their predecessors in the Euro-American art scene, the global discourse and practices are in fact specifically adapted and modified for local needs.

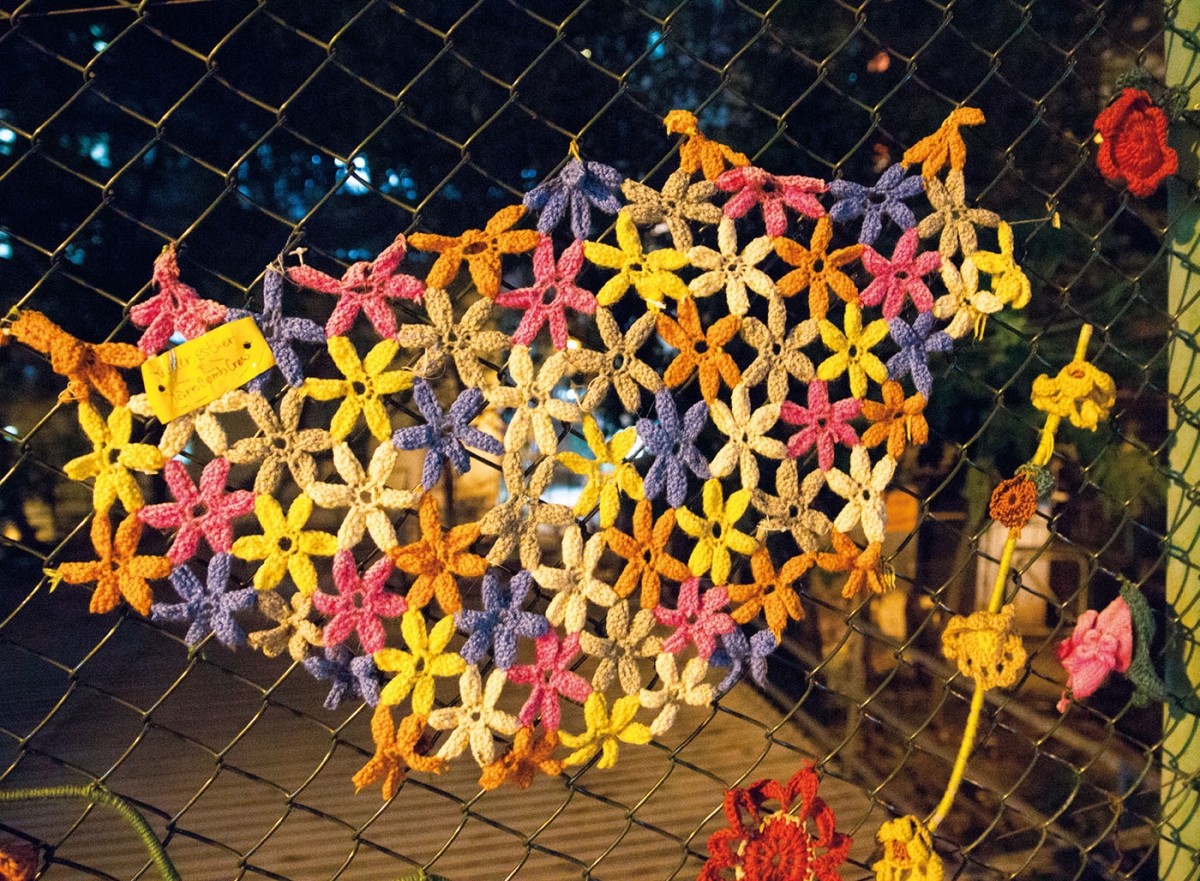

Amidst the growing economic, social, political and cultural disparities in cities in East Asia, informed discourse between different social groups is needed to ensure a more socially just future at the nexus of globalization, digitalization, neoliberal capitalism and environmental crises. Alternative artistic and creative practices, such as workshops, collaborative art projects and creative interventions in the urban public space, are continuously transcending the dichotomies of art and everyday life in East Asia. From alternative art spaces to one-time interventions in urban public space (e.g., urban knitting, fig. 2), they provide innovative platforms and discursive sites for different stakeholders to engage with each other. While doing so, they respond to sociologist Manuel Castells’ call that the growth of the global civil society depends on spaces “where people come together as citizens and articulate their autonomous views to influence the political institutions of society.”7 Aside from the mere beautification of urban public space, alternative artistic and creative practices are instrumental in providing new methods to transform spaces into places, and at the same time, to promote, for instance, community building, belonging and environmental preservation.

Alongside discursive sites, alternative artistic and creative practices support the emergence of new subjectivities and forms of civil participation. Rather than relying on an artist’s aesthetic authority over his or her art work, the practices expand new possibilities for varied agencies to emerge and participate in the creation processes for artists, citizens and other professionals alike. Whether taking the form of a shared breakfast made from local food or digital storytelling workshop encouraging people to share their experiences, the responsibilities of engagement are shifted to participants. Following art historian Grant H. Kester, the shared practices can be regarded as ‘dialogical art’, with an emphasis on exchange and partnership instead of the artist’s authorship and aesthetic autonomy. A more nuanced study of these art practices, as Kester rightfully emphasizes, “can reveal a more complex model of social change and identity, one in which the binary oppositions of divided vs. coherent subjectivity, desiring singularity vs. totalizing collective, liberating distanciation vs. stultifying interdependence, are challenged and complicated.”8

The forms of alternative artistic and creative practices today, however, go beyond art practices initiated and led by professional artists. As shown in this special issue, a professional artist might prefer to take up another role, remain anonymous or collaborate as a citizen, activist or protestor, instead of be identified as an artist. In addition, citizens, activists, designers, educators, professors and/or varied institutions can launch artistic and creative initiatives for community building. Based on my own comparative research on urban creativity in East Asia, I posit that instead of focusing on professional artists and their projects, close analysis of more versatile practices are needed in order to transcend the binaries in perceptions as Kester suggests. An understanding of the shifting agencies in the alternative artistic and creative practices will reveal more intricate interrelations of societal changes, citizenship, art and creativity.

Furthermore, in addition to innovative collaborations and agencies, unseen aesthetics are gaining ground and leading to debates on evaluation criteria. To be reductive, the dispute seems to oscillate between two main opposites that value either the affective or aesthetic elements of an art work. Despite the recent desire to revive the importance of aesthetics, the question of the extent to which aesthetic qualities matter, or if they even do at all, is currently under discussion. To emphasize the value of aesthetics and to erase current dichotomies, art historian Claire Bishop draws on philosopher Jacques Rancière’s insights on art’s affective capability to open possibilities for “rupture and ambiguity” and “art as autonomous realm of experience”. For her, aesthetics - and art - always include the ameliorative possibility for social change.9

Unexplored horizons

Art researchers, artists, art activists and art organizations are pushed to reconsider the role of aesthetics, arts and creativity in social transformation in East Asia. The locally-adapted but globally-linked alternative artistic and creative practices negotiate regional values interrelated to socio-political and cultural issues along with the hierarchic value structures of the global art scene. The authors of this special issue make explicit some of the most topical contradictions and competing stakes of alternative artistic and creative practices in East Asia today. Together they exemplify how the interdependence of social transformation and alternative artistic and creative practices requires more nuanced research through specific local and regional perspectives. By bringing these authors together, I hope to foster the transdisciplinary discourse on the reciprocal relationship of arts, creativity, design, DIY culture, civil participation, urban planning, cultural policies and governance. The close analysis of alternative artistic and creative practices based on studies crossing the disciplinary boundaries can bring forward new horizons and a better understanding of the significance of social transformations emerging in East Asia today.

Minna Valjakka, Research Fellow, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore (arivmk@nus.edu.sg).