Technologies of Learning and Islamic Authority

Over the last two decades, the uptake of media and communications technologies into religious practice has been a striking phenomenon in Indonesian Islamic society. It is commonly connected with the emergence of a Muslim middle class. 1 Islamic banking and financial products, social media, Islamic fashions, Islamic television drama, preachers with styles aimed at middle-class sensibilities, extended pilgrimage tours are markers of increased prosperity amongst the Muslim community. They also correspond to emerging loci of authority in the Muslim community. After all, new communications and media technologies involve the arrival of new forms of authority, and the weakening of others.

Communications technologies have effects more broadly than class division alone. They are also highly influential in one of the most significant divisions in Indonesian Muslim society, namely the one that differentiates traditional from modernist Muslims. A fascinating example of the relevance of technology to this ongoing divide is the ‘yellow books’ (kitab kuning), which are the texts used in the learning practices of traditional Islamic schools (pesantren). 2 This learning technology is certainly not new, but it has recently acquired an expanded political meaning.

In 2019, the Indonesian parliament passed the ‘Pesantren Law of 2019.’ This is the latest in a string of reforms, commencing in the 1970s, through which the Indonesian government has sought to bring the country’s traditional Islamic schools – pesantren – within the orbit of state-provided education. The pesantren environment is a very hierarchical one, presided over by the figure known as kyai (equivalent to school principal), who is qualified to lead the community by virtue of qualities such as scholarly achievement, family lineage, and charisma. The Pesantren Law of 2019 formally affirms the kyai and pesantren as official components of the national education system. For the first time, the ‘yellow books’ are formally stipulated (in sub-article 1(2)) as a defining feature of pesantren education.

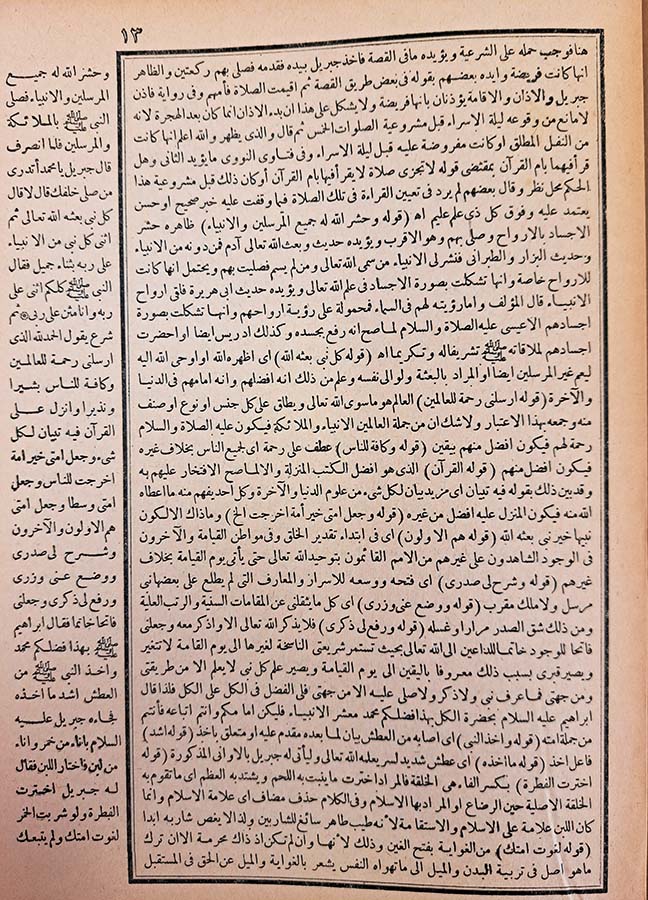

The books are distinctive due to the yellow paper on which they are printed. Their true uniqueness, however, lies in the way they express and affirm the traditional hierarchy of the pesantren world.

Fig. 1: Students of the ‘yellow books’ internalise scholarly lineages when they study a text side by side with a commentary on it by a related scholar. (Photo by Julian Millie)

There is a close fit between the ‘yellow books’ and the hierarchical pedagogical styles of the pesantren. 3 Many kyai are known for their mastery of specific works, and advanced students often plan their study programs around the reputations of individual kyai who are renowned as teachers of specific works. Such students participate in learning practices that are heavily determined by the pesantren hierarchy: the kyai progresses through the book, translating and interpreting while the students take notes and listen. On finalisation, the student receives a qualification that ties their achievement to the name and reputation of the kyai. The completion of the book enables the student to become a new link in the teacher’s genealogy.

The physical form of these books is shaped by this pedagogical context: the language is almost always Arabic, the mastery of which is a basic competency of the kyai. The books are written by scholars revered in lineages that are commemorated in the pesantren, space is sometimes provided under each line of text for annotations that are added during the face-to-face learning practices, and commentaries by other noted scholars are published in the spaces around the primary text. Based on these features, the yellow books are learning technologies that preserve the hierarchies and genealogies that define the pesantren world.

Other groups in Indonesia’s Muslim community have moved past this media technology. Modernist Islamic educators have adopted pedagogical styles from secular models that have enormous authority in Indonesia, and use the same classroom styles and textbook formats as are used in the non-religious educational system. They have largely abandoned this book technology, along with the hierarchies that it reflects.

Yet, for a numerically significant segment of Indonesia’s population, the ‘yellow books’ must be preserved in Islamic education. Teachers in the pesantren watched on throughout the early and mid-twentieth century as modernists took up new learning technologies, ones that seemed more appropriate for evolving social and political conditions, but refused to ‘downtake’ the yellow books, realising their important role in preserving the distinctiveness of this religious segment.

That is why the statutory definition is so important. By defining the pesantren as an institution where the ‘yellow books’ are taught, the government is formally bringing the hierarchy of the pesantren environment closer to the centre of public life in the Republic.

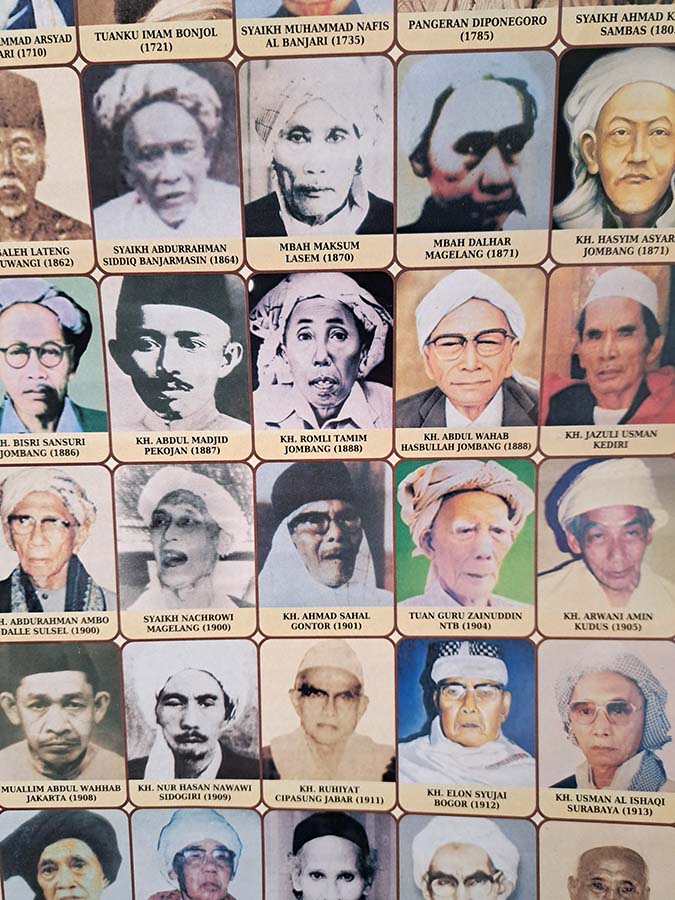

Fig. 2: Posters such as this one, photographed by the author in a pesantren, inform students about genealogies of teachers and scholars. (Photo by Julian Millie)

This definition was opposed by modernists before the passing of the bill. 4 They queried, amongst other things, the way the bill constructs within the national education system a particular educational space specifically around the pedagogical traditions of a single segment. Behind this concern is a conviction that the national education system ought to be available universally for all Indonesians on equal terms.

As is often the case with Islam and public life in Indonesia, practical politics is part of the conversation. The current government has obtained crucial electoral support from the populations in which the ‘yellow books’ are authoritative learning technologies. The success of the current President, Joko Widodo and his party relied upon voters in these communities, especially in Java. The formal recognition of the pesantren and kyai, along with the financial largesse that might flow in its wake, are regarded by many as sweeteners for its voting constituency.

Although they do not feature in the media studies conversation about religion and emergent class, the ‘yellow books’ are a striking example of the connection between technologies of mediation and religious authority. What is under focus here is not the uptake of new technology by a Muslim segment, but a refusal to ‘downtake’ a specific mediating technology. The technology is essential to the preservation of a nationally significant Islamic culture. On the broader public stage, however, its affirmation within the national educational repertoire might turn out to be a fragmenting move.

Julian Millie is Professor of Indonesian Studies at Monash University. His research concerns the social and political meanings of Islamic practice in Indonesia. Email: Julian.Millie@monash.edu